Life as a factory girl: Gruelling work, camaraderie and sexism

- Published

Between the 1960s and 1980s, thousands of women worked in factories in the south Wales valleys

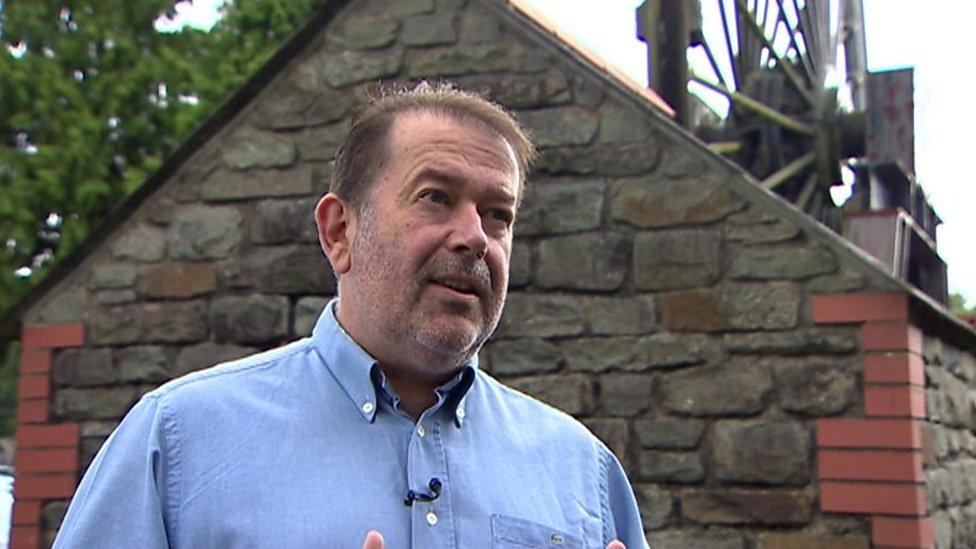

In the 1960s, the south Wales valleys were awash with industrial clothing factories. Forming the bedrock of local employment, they were known for their gruelling hard work, camaraderie, inequality and sexism. Here, in her own words, machinist Terry Jones, 67, explains what it was like to be a factory girl between 1966 and 1975.

I remember one morning in the factory, coming back from break and seeing a note propped up against my sewing machine.

It read: "Will you be my girlfriend?"

I flushed bright red and shoved it in my bag.

But the whole day, the girls kept playing the LP of Susan Maughan's "Bobby's Girl" over and over.

Lo and behold, it was a man called Bobby who left the note, but he was three years older than me - ancient at 20 - so nothing happened other than me feeling incredibly embarrassed.

Looking back, this was a sweet, innocent moment from the factory floor that shows how green I was.

Perhaps it wasn't surprising, though.

I had joined the industry straight from school, aged 15 and a half, and it was the first I knew of the world.

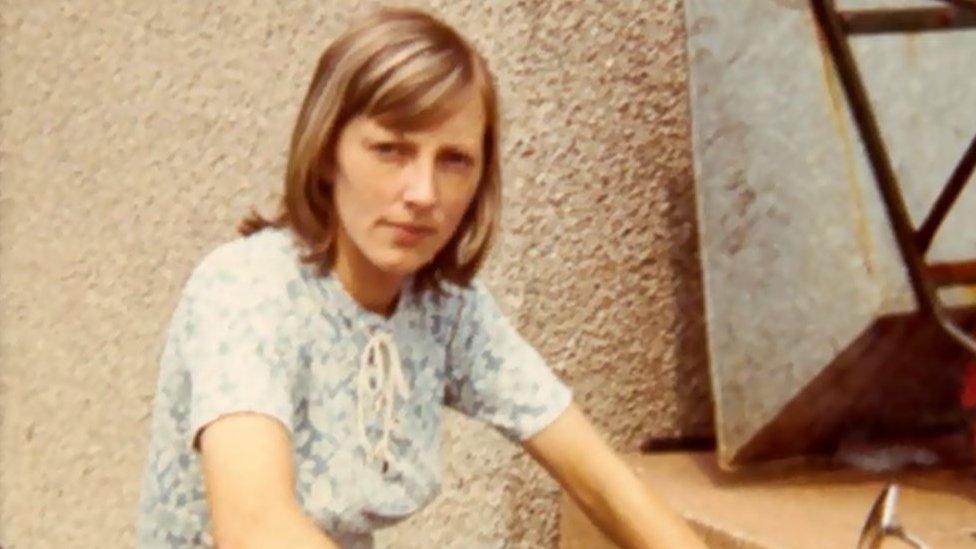

Terry in her younger years growing up in Ystrad Mynach

Not interested in further education or college, I had wanted money and some independence, and the factory seemed the obvious place.

I was already pretty good at knitting and crocheting, having made lots of my own miniskirts and tops by hand.

But the work in the factory was on a completely different level.

Even the training was almost impossible.

We were using Pfaff and Singer industrial machines that were incredibly dangerous as they went so fast.

We had to sew around paper squares and do circles and zigzags, practising stopping and starting the treadle pedal.

Then we were tasked with working against the clock, to see if we were quick enough.

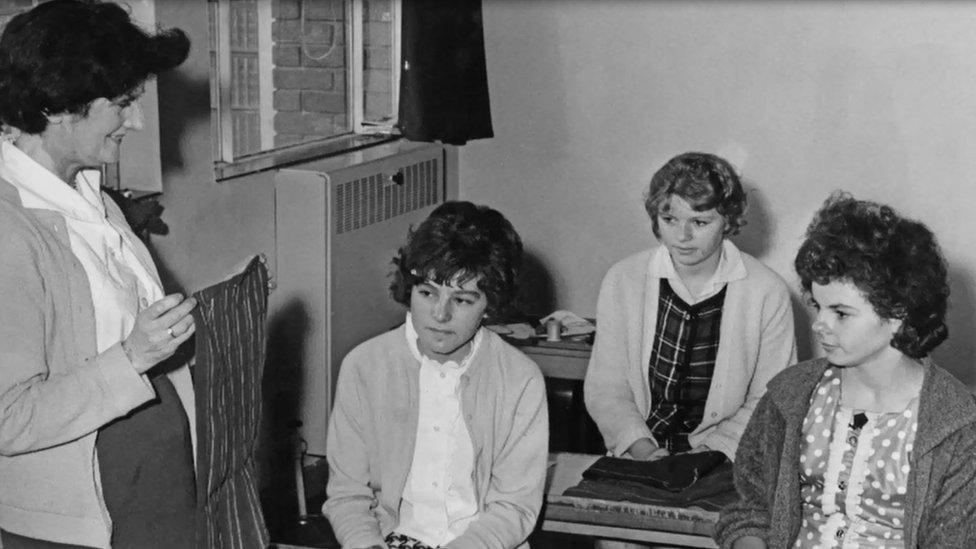

Women worked in rows one behind each other, with the most experienced at the back

It took five long months before I was ready for the factory floor.

There, I joined hundreds of women, all largely making high-end Mary Quant coats, with checks and stripes.

You started on the easy stuff - sewing in the labels and the lining of garments.

But the highly skilled women at the back of the room were on pockets, zips and buttons.

Standards were incredibly high, with work sent back to you if it wasn't perfect.

But you had to be quick, too.

We went like the clappers, working 08:00 till 16:00 to the hooters or bell, listening to LPs we brought in, like Cilla Black or The Shirelles.

The machinists spent months training before they were allowed on the factory floor

Looking back, there wasn't much heed for health and safety.

The noise was terrific, even with cotton wool in our ears, and all of us at some point ended up with a needle through the finger.

If it went straight through, you would need to go to the local hospital.

But I hardly ever remember these incidents being logged in an accident book.

Terry formed friendships for life working in the factories

The pay-off was the decent money we got - roughly four pounds a week.

I gave my mum one pound, five shillings for lodgings, and forked out nine shillings, 11 pence for my weekly bus ticket.

But the rest I kept to myself, spending it on clothes or dancing or going to the pictures.

You might also like:

It was the start of the revolution of women having spending power, but I always made sure I saved some too, opening a Post Office savings account and putting in two shillings a week.

The factory life was about far more than just money, though.

This was the key time in my life where I grew up - changing from a girl to a woman.

The factories normalised women at work and helped move on the campaign for equal pay

In some regards, it was quite a frightening place to work.

Some of the women were terrifying - it was very territorial and you couldn't just sit where you wanted.

Pranks were pulled and I remember the older women sending me up to the store room to ask for rubber needles or spotted cotton - neither of which existed.

The keeper would just say: "You're new, aren't you? Tell them to get stuffed. And pretend you knew there was no such thing as rubber needles."

Once, my friend Gary - also new - got sent to ask for a bucket of steam for the Hoffman clothes press. We were so naive.

If a girl got married, we would be very cruel to her too.

We would find her coat and sew big 'Ls' on it for learner or big willies made out of fabric.

We'd even blow up Durex and stick them on, and she would have to wear this on the bus home.

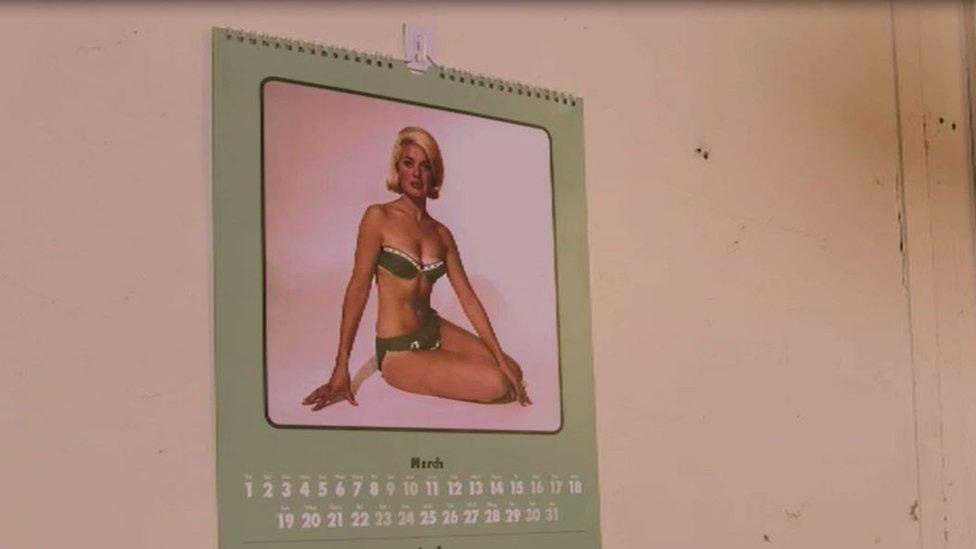

It was perfectly acceptable for calendars of women to be up on the factory walls

But the camaraderie and sense of fun was brilliant.

There was always someone having a cigarette or their ears pierced in the loos.

The language was foul - "pit language" my mother called it.

But for the most part, the girls were like family.

They taught me the facts of life - about sex, love, relationships, which I'd never learnt at school.

And they'd be there for you if you got dumped or had a crisis.

If someone got married, we all got invited, and we'd take some sandwiches and a cake along.

Same if someone was pregnant.

We would make baby coats and hats, and blankets for the cot.

We didn't have a lot of money but we were all in the same boat.

We worked together, then on Friday nights or on the weekend, went out together for fun.

Asking the female workers to model bras and swimwear was commonplace

Of course, this was a different era for women's rights.

On one occasion, in 1971, the factory took on an order to sew new bras, and the bosses asked if I would model one to show what it looked like.

So I put it on and sashayed up and down the factory floor, perfectly happy because it meant I got to keep the garment afterwards.

The bosses were all men, and thought nothing of hanging calendars of half-naked girls in their office.

And if a machinist got pregnant, I believe they were effectively sacked at six months and often not taken back.

This led - in the 1970s - to some industrial unrest, with female workers demanding, amongst other things, equal pay for equal work.

Many women went on strike to secure equal pay

But, to be honest, the way things were didn't bother me.

My view was that the men were the bread winners, and so were entitled to be paid more.

It was up to a woman whether she worked or not - some did and some didn't - so it still fell on the men to keep them.

The money I earned was pocket money to me.

So I also didn't mind - when I got married - that I came home from work and did the cooking and dishes too.

I was just living out a life that I'd seen my parents do before me.

Terry married her sweetheart Ken in 1970 when she was just 19

Of course, I slowly learnt that it was a man's world and things needed to change, but this was largely after I left the factories and got a job as a lorry driver.

I would take samples of material or curtains up to Luton or Birmingham, or to Liberty in London for exhibitions.

I loved it but the men made it very clear they resented me being a driver.

Then, all too soon, came the 1980s and the closure of the factories.

The work had all moved overseas and the effect it had was devastating.

Terry still sews her own curtains, though she admits she is not as quick as she used to be

We had been the best machinists in the world, and now we felt bereft, as if something had been taken from us.

Today, there is no industry in the valleys, except IT.

Young people leaving school have no choice but to move out and seek work elsewhere.

Our factory world may not have been perfect, but it was one of the happiest times of my life.

Sadly, today's young girls of the valleys will never know what they have missed out on.

The last episode of Back in Time for the Factory airs on Wednesday 10 October at 8pm on BBC One Wales. The series is available now on BBC iPlayer.

- Published21 November 2017

- Published4 May 2014

- Published17 August 2017