Fruit flies' brains studied to help crack dementia

- Published

A fruit fly, magnified

The humble fruit fly could help scientists unlock the secrets of Alzheimer's disease.

A new £20m Dementia Research Institute at Cardiff University includes a fly laboratory.

Researchers will be studying the brains of the flies because they share a large proportion of their genes with humans.

They also have a £1m microscope to hand, which is able to carry out thousands of tests on cells and collect data automatically.

In Wales, there are 45,000 people living with dementia but this is set to increase to 100,000 by 2055.

Cardiff is part of a new £290m network of dementia research centres, which includes Cambridge, Edinburgh and London, looking to find a cure.

A model of a fruit fly's brain - 50,000 bigger than the original

The fruit fly has a part to play because it has many genes which are similar to those in Alzheimer's disease in humans.

Its brain - roughly the size of a poppy seed - contains about 100,000 neurons; human brains have 100 billion.

But only having a life cycle of a few months, scientists can track how the fly's brain ages far more quickly.

A mutant fruit fly - with the white eye - is highlighted here, which can be studied to see genetic changes

Dr Owen Peters, a lecturer and one of the researchers, said the flies can help us understand brain function.

"Flies allow us to do imaging techniques which we aren't able to do in other model systems," he said.

"If we find a gene in the human genetic studies that looks like it's linked to Alzheimer's disease - and flies have it - it allows us to have a very rapid, inexpensive system, which we can test to see how these affect brain function."

Fruit flies are just a small part of the genetic research which is looking to understand better how a family of diseases, which also includes Parkinson's and Huntingdon's, behave.

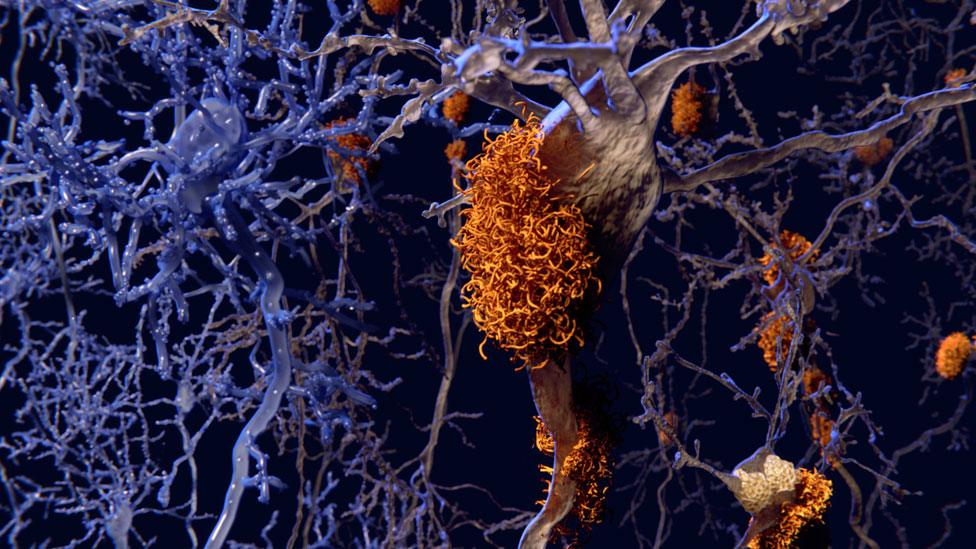

Could the body's immune system play a role in brain diseases?

Genetic studies have suggested that the body's own defence system could contribute to Alzheimer's disease. In normal circumstances - for example when a baby's brain is developing - the body's own response serves an important purpose - helping to "prune" the brain of "rubbish" and get rid of "redundant" tissue that's damaged or died.

However it's thought in diseases like Alzheimer's that response somehow could be damaging healthy cells

Paul Morgan, professor of immunology, will be trying to try to develop a better understanding about those mechanisms

"We know now what we thought of as brain-rot, a slow decay of the brain in people with dementia - isn't that at all. Instead it's an inflammatory disease where the inflammation is driving the destruction of brain cells," said Prof Morgan.

"And knowing that give us new approaches to therapy because were good at treating inflammation in other diseases like arthritis and we can now start thinking of applying those approaches to brain diseases like Alzheimer's."

Prof Julie Williams, associate director of the institute, said with a team of more than 70 scientists in Cardiff and collaboration within the network, she believes it marks a "step change" in the way this set of diseases is studied.

"There are thousands of genes which will affect our susceptibility to develop these diseases so we can now capture most of that information so can indentify people who will be at a very high risk of developing the disease in the future," said Prof Williams.

"That will allow us by using samples to create cell models - mini-brains based on stem cells which we can grow and to mould into different tissues - so we can model the disease in a way we've not been able to do in the past."

Dr Owen Peters with the robotic microscope and a scientist at the institute using a more conventional model

The Welsh Government is funding a £1m robotic microscope - made in Llantrisant - which is able to scan and analyse thousands of individual cells at high speed.

Health Secretary Vaughan Gething, officially opening the institute, said the investment "demonstrates our commitment to tackling this devastating disease and forms part of our plan to make Wales a dementia-friendly nation, as set out in our Dementia Action Plan, external."

- Published23 September 2016

- Published20 May 2016