Could Wales face a repeat of 2018's extreme weather?

- Published

In 2018 Wales was hit by floods, a big freeze and wildfires

When it came to the Welsh weather, 2018 was a year of extremes.

The coldest ever daily average March temperature was registered during the "Beast from the East" storm and three months later, a record June heatwave parched the landscape.

Then in October, Storm Callum inflicted some of the worst flooding for 30 years on parts of the country.

So do the floods, freeze and fires of 2018 offer us a glimpse of the future?

Met Office experts who study long-term weather trends produced a State of the UK Climate report which found a repeat of the 2018 heatwave is 30 times more likely, external because of climate change.

By 2070, average summer rainfall could decrease by up to 47% while average summer temperatures could be up to 5.4C warmer.

On the other hand, winters are likely to be wetter and warmer - the conditions which create storms.

2018: The fires

Motorists watch the fire above Horseshoe Pass

While the winter snow and ice was still fresh in the memory, the hottest June on record in Wales was just around the corner.

And while July and August did not break records, 2018 was the warmest and sunniest since 1995 and the driest since 2006. Reservoirs shrank, ancient hillforts and Roman settlements were exposed as the grass wilted and on hillsides and mountains the tinder-dry vegetation was ready to burn.

In July, a blaze on Twmbarlwm mountain, near Newport, occupied firefighters for more than two weeks. Elsewhere moorland above the Horseshoe Pass in Denbighshire and the upper slopes of Maerdy Mountain in Rhondda Cyon Taff were left black and smouldering.

The fires put an enormous strain on the emergency services.

The smouldering landscape caused by a wildfire on Llantysilio Mountain in Llangollen

"The climate of Wales is warming," said Met Office scientist Mike Kendon.

"That's consistent with the overall climate of the UK warming, which in turn is consistent with the global climate warming."

His team produces a huge amount of data every year, monitoring temperature, sunshine and rainfall trends. While he is keen to point out that there can be many short-term variables in the weather, Mr Kendon said the overall direction was for a warmer climate.

The Met Office looks at average temperatures in 30-year blocks. From 1961 to 1990 the baseline long-term mean average temperature for Wales was 8.6C (47.48F).

Between 1981 to 2010 it was 9.1C (48.38F) and in the 2008-2017 statistics recorded to date it was 9.4C (48.92F).

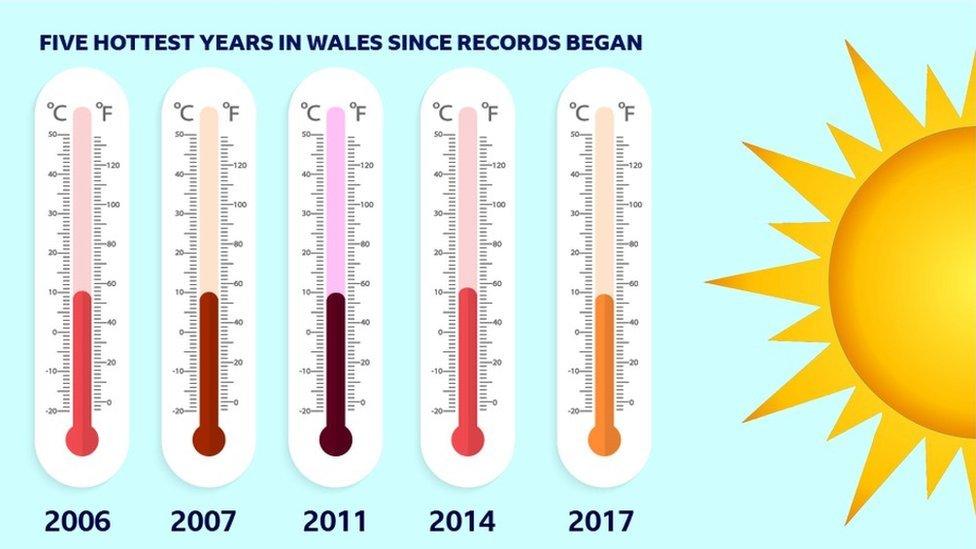

Average temperatures. Source: The Met Office

"We had a series of summers between 2007 and 2012 that were very disappointing and the summer we have just had is clearly in marked contrast to those so we have to be careful," Mr Kendon said.

"There's clearly a long-term warming trend but also the potential for annual variability.

"The reason for that is that Wales is very small and is on the edge of the continent with the weather being dominated by the Atlantic, which means that small shifts in the position of the jet stream and associated low pressure systems can result in very large changes in the Welsh weather over the course of the seasons."

2018: The floods

Huge waves crash into the seafront at Aberystwyth

In October, Storm Callum brought the worst flooding in 30 years to parts of Wales.

The Towy burst its banks in Carmarthen, breaching the town's flood defences, a man was killed by a landslip at Cwmduad, and the River Teifi at Llandysui reached its highest level since records began.

On 12 October, Capel Curig in Conwy county, was among the wettest places in the UK, with 46.2mm (1.8in) of rain falling, while in Libanus, Powys, 152mm (6in) of rain fell in one day.

The River Taff flowing at a high level through Cardiff during Storm Callum

Cardiff University emeritus Prof Roger Falconer was invited to a high-level committee meeting in Westminster in 2012 just after flooding hit Cumbria.

"I'm listening to the Met Office report and these are world class people with world class reputations in climatology so anything they say you have to take seriously," he said.

"They start talking about 'black swans' which are extreme events - a term I'd never heard before.

"Then they said that extreme rainfall events in the UK could increase by 30% over the next 20 years. That's a really major uplift in rainfall intensity."

The meeting looked at flooding in England, but the statistic immediately made him think of what could happen in Wales.

Prof Falconer pointed to flooding in Boscastle, North Cornwall, on 16 August 2004 where so much rain fell that river levels rose two metres in one hour.

Some of the most striking images from the Storm Callum floods

The rain had travelled a short distance from the deep-sided valleys to rivers with 58 properties flooded, 100 people were rescued from trees or rooftops and 150 vehicles were washed away.

"We have Boscastle-type landscapes all round Wales," he said.

"The problem we have in Wales is that if you get a massive storm, it almost straight away, rushes down the river and causes massive damage.

"The Taff is not different from the Conwy or The Dovey - you can go all round Wales and pretty much every river flows from the mountains to the sea over a very short distance through steep terrain.

"The Taff is a really good example. It rises really quickly and drops really rapidly.

"You go to the Severn and it's the opposite. It takes days for a flood to get down to somewhere like Upton-on-Severn - they have all the time in the world for people to move all the furniture up to the first floor of the house."

2018: The freeze

Traffic struggles along the A4232. Heavy snow affected Cardiff and other parts of South Wales during the 'Beast from the East' storm in March

So if our climate is warming, does that mean that the classic images of fields and mountains covered in snow will become just a memory relegated to Christmas cards and old photos?

Not if what happened in March is anything to go by. Just when it felt as though spring was around the corner, the cold returned with a vengeance.

The "Beast from the East", a weather system from Siberia, blasted Wales with high winds and freezing temperatures.

When this cold front met the moisture contained in Storm Emma, it generated a rare Met Office red warning for snow for the south of the country.

Snow fell on the Prince of Wales Bridge during the 'Beast from the East' storm in March 2018

On 1 March, when the freeze was at its most ferocious, a weather station at Tredegar recorded a daily maximum temperature of -4.7C (23.54F). In a year of records, this was another - a new record low for a daily temperature recorded in Wales in March.

The Met Office data suggested winters will get warmer, but also wetter, which means that when it does get cold enough to snow, there will be enough moisture in the air to produce disruptive amounts.

"Wales also had some very severe weather back in March 2013 which caused quite a lot of problems for farmers in the higher regions," said Mr Kendon.

"So those two severe spring weather events demonstrate that we can still get severe winter weather."

- Published4 December 2018

- Published6 December 2018

- Published15 October 2018

- Published8 July 2018