Race in books: 'Why I write stories for my mixed-race sons'

- Published

Whose story are we actually telling?

"Tokenism" in books led a father to write and self-publish stories for his mixed-race sons.

Suhmayah Banda, from Penarth, Vale of Glamorgan, said he wanted to write stories that "would allow my kids to see characters that look like them".

A report for the Book Trust said one third of black, Asian, and minority ethnic (BAME) authors and illustrators in the UK self-publish.

That compares with 11% of white authors and illustrators.

"As a family we read a lot together, and there are so many varied characters out there - animals, monsters, cars, firemen," said Mr Banda, who is originally from Cameroon.

"But when it comes to ethnically diverse, in my case black or mixed characters, there is just not that much choice out there."

A study by the Centre for Literacy in Primary Education in 2017 found only 1% of children's books published that year in the UK had a BAME main character, and only 4% included BAME background characters.

The 2011 census found 14% of people in England and Wales were non-white. In Wales the figure was 4.5%.

'I didn't like the generalisation'

Mr Banda's characters are based on his sons Tancho, eight, and Charlie, six, and the stories take them on adventures inspired by their recent travels as a family, after moving from the family home in Surrey and settling in Wales in 2018.

But one of the catalysts for his first story was a comment Tancho made after reading a book in school.

"He came home from school one day and told me that people in Africa don't have water in their houses. And as an African, and a Cameroonian specifically, I was a little surprised," he said.

"I was like, 'Really? All of Africa?'...there are a lot of people who have and don't have things everywhere in the world, so I didn't like that generalisation.

"Books are the first exposure a lot of kids and adults have to the wider world. And if those books are always written to the same narrative, in many cases misleading or wrong narratives, then it is dangerous on a lot of levels.

"And I wanted to expose my kids, and hopefully others, to a lot more perspectives."

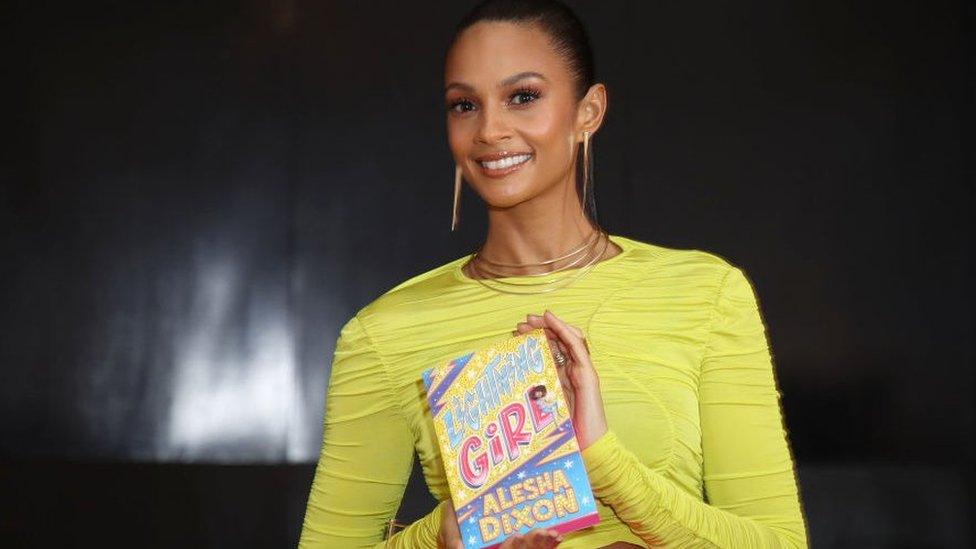

TV star Alesha Dixon created a black female superhero - but non-white characters are underrepresented overall

Mr Banda, whose day-to-day job is in IT, is sceptical about efforts in the publishing industry to improve representation.

"They have a lot of competitions going on about promoting diversity. I find them flawed at best....

"You end up having a black or ethnically diverse character put in a story that doesn't really reflect their reality. A lot of the time that is just tokenism," he added.

The Publishers' Association is now producing annual data, external on the diversity of the workforce. Its 2018 survey suggested 11.6% identified as BAME, below the UK figure, and the report did not look at ethnic diversity in leadership positions.

Aimee Felone, who co-founded publishing company Knights Of, shares Mr Banda's frustration with much of the sector.

The company's starting point was to hire "as widely and diversely as possible to make sure the books we publish give windows into as many worlds as possible".

It has just published its first novel, a children's murder mystery where the detectives are two young black sisters in London and, in October, they will be publishing a story about a character who is hard of hearing.

They purposefully chose a deaf editor to work on it, to make sure the story was "genuine and authentic".

'Whose story are we actually telling?'

In her view, the approach of the industry to BAME stories often grouped together non-white people from different backgrounds.

"I think what is missed is that there are different challenges that are faced within each community," she said.

"We're not looking at representations of Asian women, Chinese women [for example], we're just putting everyone together in one box [and saying] 'Oh look we have a BAME character'.

"What does that actually mean? Whose story are we actually telling?"

Stephen Lotinga, chief executive of the Publishers Association, said companies recognised the need for greater diversity in children's books, and the sector was "supporting the search for new talent, sponsoring relevant prizes and running schemes and initiatives to support diverse new voices" and wanted to better understand the issues.

"It is very important for young people to see themselves in the work," says poet Karl Nova

The hip hop artist and poet Karl Nova, who has been visiting schoolchildren in Wales as part of Hay Festival's "Scribblers Tour", external, agreed it was very important they see themselves in literature.

He said he hoped to challenge children's ideas about poets, and about the dominance of white writers.

"My doorway into literature was rap and slam poetry, that was my way in and then I circled all the way back to the classics anyway," he added.

He said young people need to be able to identify with the work.

"They can connect with it, and they can walk through those doors. There's a whole beautiful world for them to explore."

- Published17 April 2019

- Published2 April 2019

- Published24 January 2019