Forensic science: How pollen is a silent witness to solving murders

- Published

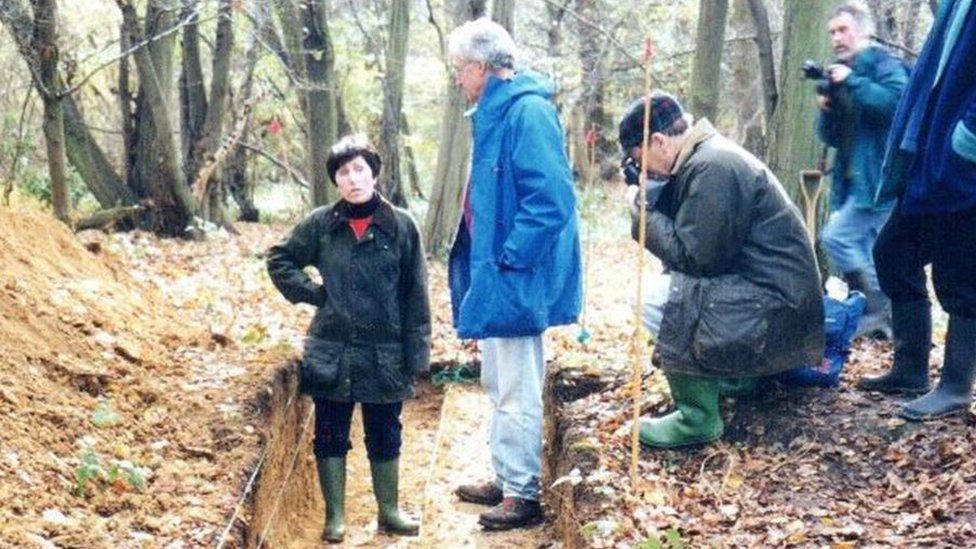

Prof Patricia Wiltshire giving advice to archaeologists in the early 1990s

She is one of the world's leading forensic ecologists who has helped gather evidence for some of the highest-profile murder cases of recent years. But Prof Patricia Wiltshire's interest in the botanical world began during her childhood in Wales.

Ms Wiltshire, 77, remembers with fondness the walks she went on with her grandmother, Vera May Tiley, that introduced her to the natural world.

She said: "We lived in a small mining village, Cefn Fforest, near Blackwood in the South Wales valleys.

"We would go on walks and she would show me things in hedgerows; birds' nests, insects and plants we could eat, like hawthorn and wild garlic.

"She was also a good gardener and keen to protect her plants from pests, so I learnt about plant diseases and how to grow food."

Prof Wiltshire during her first year of grammar school in 1953

Ms Wiltshire's interest in plants grew further after an accident when she was a young child.

She said: "When I was seven, I decided to scare my mother by jumping out on her and shouting 'boo', not realising she was carrying a pan of hot chip fat.

"I got badly burnt and ended up covered in bandages for two years.

"I also suffered from pneumonia, measles, whooping cough and bronchitis, which left me with a chronic cough problem.

"I missed a lot of school but had my encyclopaedias, which were my joy.

"This was post-war Britain. The NHS had just been set up by Aneurin Bevan, and some of his family lived over the road, but access to treatment was still minimal."

Despite her fledgling interest in plants and botany, Ms Wiltshire had little desire to make them her academic profession after she left Lewis Girls' grammar school in Hengoed.

Instead, aged 17, she moved to London and began a job in the civil service.

For the next decade, Ms Wiltshire trained as a medical laboratory technician at Charing Cross Hospital, learning histology (the microscopy study of tissue), bacteriology, and also biochemistry (the chemical processes in living organisms).

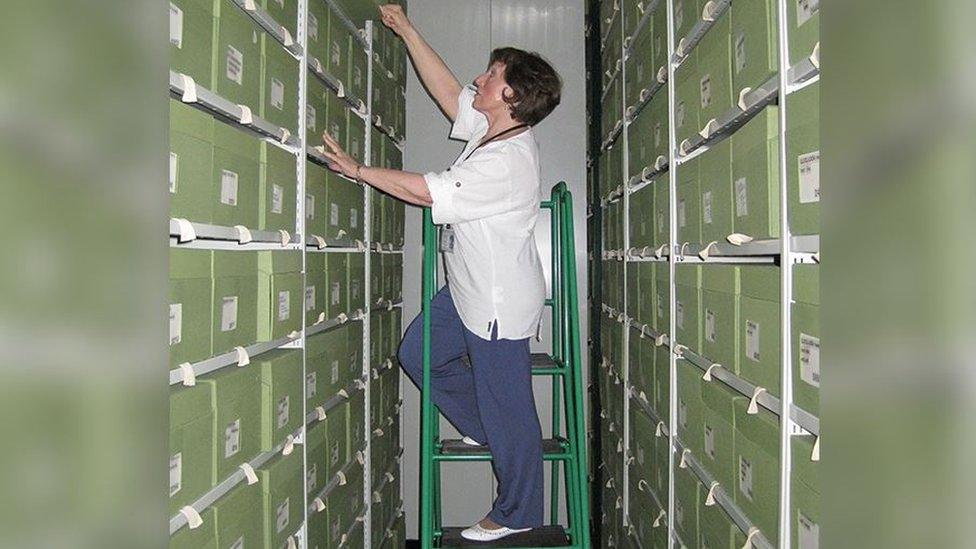

Checking reference material in the fungarium at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew

She then studied for a botany degree, becoming a lecturer and expert in palynology - the study of pollen and spores.

Pollen and spores can last for millions of years if conditions are right, even on surface soil and vegetation.

So Ms Wiltshire began specialising in archaeological sites - taking soil samples and recreating the environment in and around Roman era sites such as Hadrian's Wall in northern England and Pompeii in Italy.

'Eureka moment'

But in 1994, when she was in her fifties, she received a phone call which would change the course of her career.

It was from a police officer in Hertfordshire asking if she could help with a murder.

A charred body had been left in a ditch and there were tyre marks in the adjacent field.

Police wanted to know if a car belonging to their suspects had been present in the field.

Prof Wiltshire said: "I'd never done anything like it before, but I analysed everything in the car and found pollen from the pedals and footwell matched that of an agricultural field edge.

"When police took me to the crime scene, I was able to identify the exact spot where the body had been dumped from the types of flowers in that section of the hedge.

"It was a eureka moment for me because I didn't think it would be that specific."

Prof Wiltshire has worked on cases across the UK

Despite her own initial scepticism of forensic ecology, she began working on more and more cases.

In 2002, she helped police gather evidence in the case of murdered schoolgirls Holly Wells and Jessica Chapman in Soham, Cambridgeshire.

Police had discovered their bodies in a ditch, but wanted to establish the approach path their killer had used.

Ms Wiltshire was able to do this by analysing the re-growth of trampled plants leading to the ditch.

Police then conducted a detailed search of her route, and found one of Jessica's hairs on a twig.

Ms Wiltshire subsequently gave evidence in the trial of Ian Huntley who was convicted of murdering the two ten-year-olds.

Other high profile cases she has been involved with include the child murders of Milly Dowler and Sarah Payne, and five women murdered by a serial killer in Ipswich in 2006.

Ms Wiltshire has also worked on cases in south Wales.

Prof Wiltshire sampling fungi

She said: "In about 2005, I was called to New Tredegar in the Rhymney Valley.

"Two thugs had kicked a man to death, then dumped his body in some ferns.

"It lay there for a few days, then they returned to burn it, but people saw the smoke and called the police.

"They later arrested two men and wanted me to discover if they had been on the site."

Ms Wiltshire matched the pollen from the men's shoes to that at the scene, but was still puzzled as the pollen she discovered was not normally found in Wales.

Eventually she realised that the lorries that were trundling along the adjacent road were carrying topsoil from England, which was blowing onto the field and depositing pollen and spores.

The fact that the pollen was so uniquely located - and matched both the suspects and the crime site - led to the two men confessing.

Prof Wiltshire examining a burnt-out car

In another case in Bridgend, a body was lain on some wet, peaty soil, which preserves pollen for a long time.

Ms Wiltshire later found traces of walnut pollen in the soil and on the suspects' shoes, but she knew there was no walnut site close by.

Again, it was eventually discovered that a walnut tree had been cut down by a farmer thirty years previously. The pollen had remained in the soil ever since.

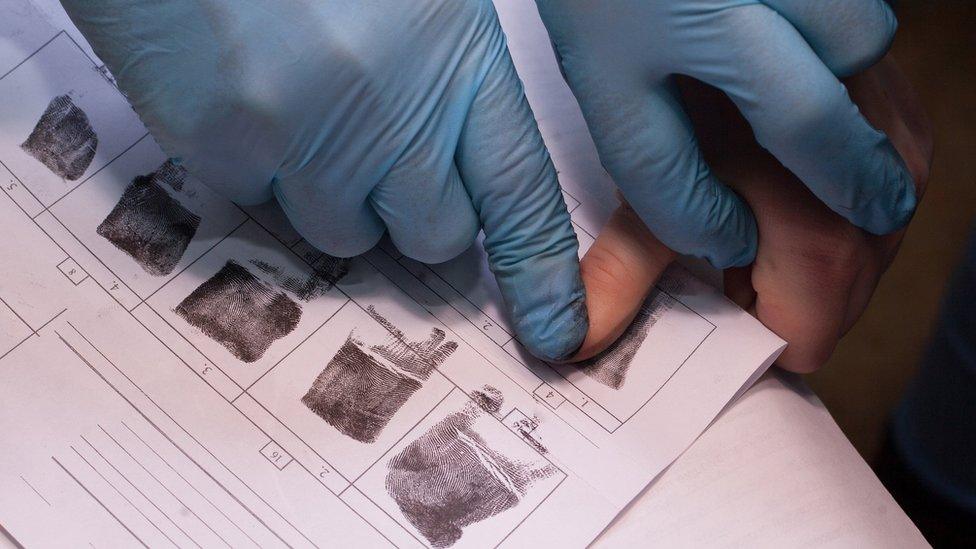

Ms Wiltshire, who published a memoir in 2019, said: "People may not realise it, but pollen and spores can tell us stuff that DNA and fingerprints simply can't.

"Pollen isn't easily washed away and it stays on people's clothes and shoes. If you walk on soil or vegetation, you inevitably pick it up."

Since her first Hertfordshire case, Ms Wiltshire has been able to use the wide range of subjects she studied to develop forensic ecology, which has helped solve many cases over the years.

She said: "Sometimes the police call me a 'Welsh witch' because of the way I process a mass of data and come up with ideas.

"But it's not magic, it's analysis."

- Published23 October 2019

- Published16 July 2019

- Published16 August 2019