Edward Colston: Wales' slavery statues 'should be examined'

- Published

Dr Chris Evans explains Thomas Picton's links

There have been calls for Wales to re-assess its monuments to slavery.

The Lord Mayor of Cardiff has called for a bust of one slave owner, Thomas Picton, to be removed from City Hall.

On Monday evening, council leader Huw Thomas said he supported the request to remove the sculpture but it would be debated at a council meeting at the "earliest possible opportunity".

One expert said each needed to be looked at case by case and the views of local communities taken into account.

"For some monuments it will be demolition or removal, or removal to a museum where they can be properly contextualised and explained," said historian Prof Chris Evans.

It comes in the aftermath of the taking down of the statue of Edward Colston in Bristol by protesters and it being thrown into the harbour.

Anti-racism protests have taken place across the world, following the death of George Floyd, 46, in Minneapolis, in the US, after a white police officer was filmed kneeling on his neck.

Dr Evans, of the University of South Wales, and an expert on slavery and the role of Wales, said the events in Bristol were "extraordinary" and reflected a debate which had not been resolved for years.

He said there needed to be more public awareness of the "ambiguous and ambivalent" roles many people played and the "deep imprint of slave-derived wealth" in Wales and elsewhere.

Dr Evans also wants more understanding of the wider impact, beyond just individuals depicted on statues.

Heroes or villains?

Henry Stanley with Ndugu M’Hali or Kalula, an African slave who returned to England with him and accompanied the explorer on a tour

Wales has not been without controversial choices for public memorials.

A statue to explorer Henry Morton Stanley was unveiled as late as 2011 in his home town Denbigh and caused controversy over claims his colonial exploits included crimes against humanity in Congo. He also had a hospital in St Asaph named after him, which had once been a workhouse where he spent an unhappy period as a boy.

There has been controversy too over Sir Thomas Picton, from Haverfordwest, the most senior general to die at the Battle of Waterloo.

He was accused of torture of a teenage girl, arrested for theft, and cruelty during his time as a governor in Trinidad.

At a high-profile trial back in London he was accused of forcing 13-year-old Luisa Calderon to stand on a wooden peg while suspended from a ceiling.

Picton argued that he was allowed to use torture to obtain confessions as Trinidad had still been subject to Spanish law

There is an obelisk monument and a controversial portrait of him in Carmarthen.

A marble bust of Picton can also be found in Cardiff City Hall, as part of a Heroes of Wales series which was unveiled by former prime minister David Lloyd George in 1916.

He is keeping company with the likes of Owain Glyndwr, Henry VII, St David, Llewellyn the Last and Gerald of Wales, as well as Bishop William Morgan, who translated the Bible into Welsh.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

The Lord Mayor of Cardiff, Dan De'Ath - the city's first black mayor - on Monday called for Picton to be removed when it was practical to do so, saying his treatment of Luisa, even in his day, was seen as "repellent".

In reply, council leader Mr Thomas said it was "very difficult to reconcile his presence in City Hall with the values of tolerance, diversity and equality which we want the Cardiff of today to stand for".

Prof Evans said there was not the same public awareness of the monuments relating to the slave trade in Wales.

"Picton came to prominence in the Caribbean and made a huge amount of money buying up plantations and owning slaves," he said.

"Both in Cardiff and Carmarthen there needs to be a debate about how these monuments to Picton should be branded.

"Do we want to dispose of them altogether or contextualise them and not see him as a military hero who died at the Battle of Waterloo but as someone who was a notoriously brutal figure in his day?"

How a reformer's statue was vandalised

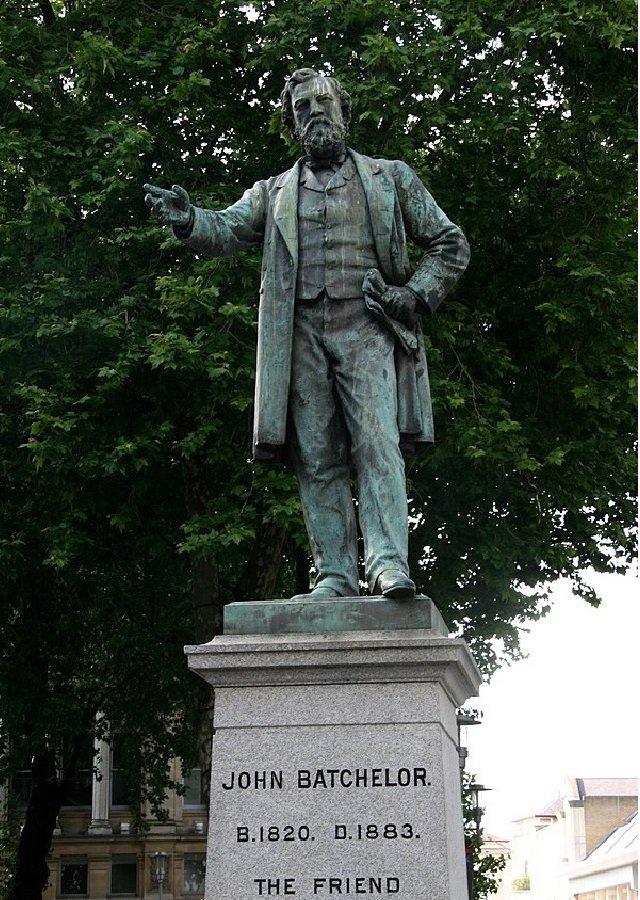

Sculptor James Milo Griffith was responsible for two statues in Wales - John Batchelor in Cardiff and Sir Hugh Owen in Caernarfon.

Owen was a major force behind setting up Aberystwyth University and widening access to schools and teacher training.

Batchelor ran a shipbuilding and docks business with his brother but "the friend of freedom", as he was later called on his epitaph, became active in local Liberal politics.

He backed causes from the abolition of the corn laws to improving public health and the rights for workers, until his death in 1883.

The statue was modelled from a very early photograph of Batchelor and depicts him addressing a crowd

Batchelor's statue, with £1,000 raised from subscriptions, was unveiled in The Hayes before a crowd of 5,000 in October 1886.

But Batchelor had enemies too ,with opponents claiming it was wrong for a memorial to such a political figure to be displayed in a public place.

In January 1887, a few months after it was unveiled, Conservative members of Cardiff town council put forward a motion to remove the Batchelor statue - backed by 1,200 names on a petition.

The Western Mail denounced the "radical mob" who attended the meeting to resist its removal and "cowardice" of councillors who "surrendered to the howlings of a radical clique".

The statue was also vandalised - with yellow paint and tar by William Thorn, from Roath, a foreman at a ship chandlers and an otherwise, it was reported, "respectable man". At his trial, it was said "political feeling had run very high in Cardiff" and the judge, admonishing local press coverage, ordered Thorn to pay £15 to charity, rather than jailing him.

There was also an extraordinary libel case brought over a "mock" epitaph for the statue to Batchelor, written by solicitor Thomas Ensor and published in the Western Mail by its editor Henry Lascelles Carr.

The alternative wording accused Batchelor of being a "panderer to the multitude" and said the monument was "erected to the eternal disgrace of Cardiff". The fact Batchelor had been dead for three years meant Ensor and Carr were acquitted.

Statues in more recent decades in the city have attracted far less controversy.

The bronze of Aneurin Bevan, NHS founder, has been a popular meeting point for rallies for more than 30 years although his head has been retro-fitted with spikes to discourage pigeons.

Judge and war hero Sir Tasker Watkins and cultural and sporting icons such as Gareth Edwards, Fred Keenor and Ivor Novello are others. No-one can object either to Billy the Seal.

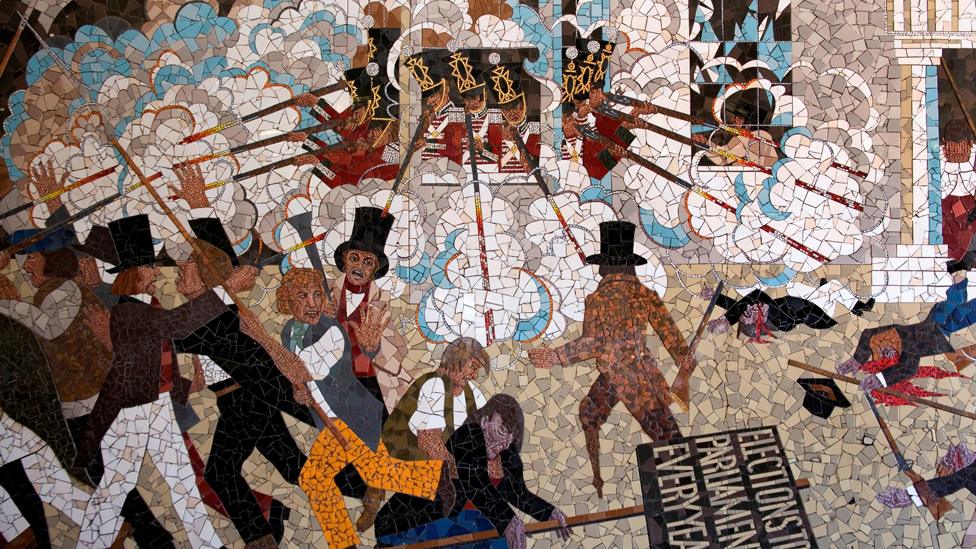

This Chartist mural made way for a shopping centre but has now been recreated

But people can get angry when touchstones to their community history are removed.

In Newport, there was an outcry after a mosaic to remember the Chartists and 22 protesters being shot in 1839, made way for a shopping development. A replacement was opened late last year.

The lack of notable women depicted on Welsh monuments has also been an issue and has now led to a statue being commissioned of Cardiff head teacher and multi-cultural education champion Betty Campbell. She was chosen after a public vote from a shortlist of five "hidden heroines".

Are statues the best way of remembering people?

"There's a problem with statues: they're solid, they don't move and they can't gesture - they say something about a particular time and space," said Dr Evans.

"The statue of Colston was erected at the height of Britain's imperialist experience, so it was making a deliberate statement, cast in bronze.

'Considered way'

"But history shifts and moves as our interpretations shift and the stories have to be relevant to the people here and now."

Ali Abdi, a Cardiff youth worker, is in favour of Picton's bust being put into a museum and his story being explained.

"We should definitely look at where it fits now in today's society," he said. "It might have fit in 100 years ago, but it might not fit in now."

Dr Leighton James, associate professor of history at Swansea University, said he does not want to see "partial historical amnesia being replaced in the long term by a total historical amnesia" and he also suggested putting statues in museums.

"If we change all the place names, tear down all these statues then, in a few generations... these people are completely forgotten and both the good and the ill is completely forgotten," he told Gareth Lewis on BBC Radio Wales.

First Minister Mark Drakeford said Wales was "not immune" from having a history in the slave trade, and said it was right the country had to "confront that rather than sidestep it".

He added: "Where we have statues to people whose histories in Wales belong in that past, and belong in that past context, rather than being on display as a form of continued celebration, then action should be taken."

Mr Drakeford said he was confident that Cardiff Council would respond in a "very careful and considered way".

- Published8 June 2020

- Published8 June 2020

- Published18 June 2015