A refugee's story: 'The execution order came for my mum'

- Published

The family sold everything they had to get to human traffickers

When Fariba Amiri gave a speech to her community in Afghanistan advocating for women's rights, she anticipated some backlash.

But she never expected the speech in 2000 to travel far and wide, resulting in an order for her to be executed.

A year-long journey to safety in Cardiff followed, with the added worry of her son's complex heart condition.

Her middle child, Hamed Amiri who was just 10 at the time, has put their experiences into writing with a book - The Boy With Two Hearts - due to be published this month.

'The execution order came for my mum'

Fariba loved cooking, and gained a local following of young girls she would teach to cook and sew.

But she became frustrated when none of the girls pursued their dreams, and felt it was her responsibility to speak out.

"In the back of her mind she thought there might be some backlash but only in our own community," Hamed said.

"The execution order came for my mum a day or two after."

His older brother Hussein had, after two heart operations, been told there was nothing more the doctors in their surrounding countries could do and he would need to seek treatment in the US, UK or Europe.

But the family had not expected to make that journey quite so soon, or in such circumstances.

"We sold everything we had, every belonging, to raise money to get to the human traffickers," Hamed told BBC News.

"Before I knew it, I was in a hidden back compartment in a car driving out of the city.

"We were in the car for a good few days and the next time we came out it's in Moscow, where we stayed for a few months."

From Moscow, they were driven to the middle of a forest and walked, with a group of other refugees, through Ukraine and Poland.

They obtained fake passports - Hamed believes from a member of the mafia - which allowed them access to private planes.

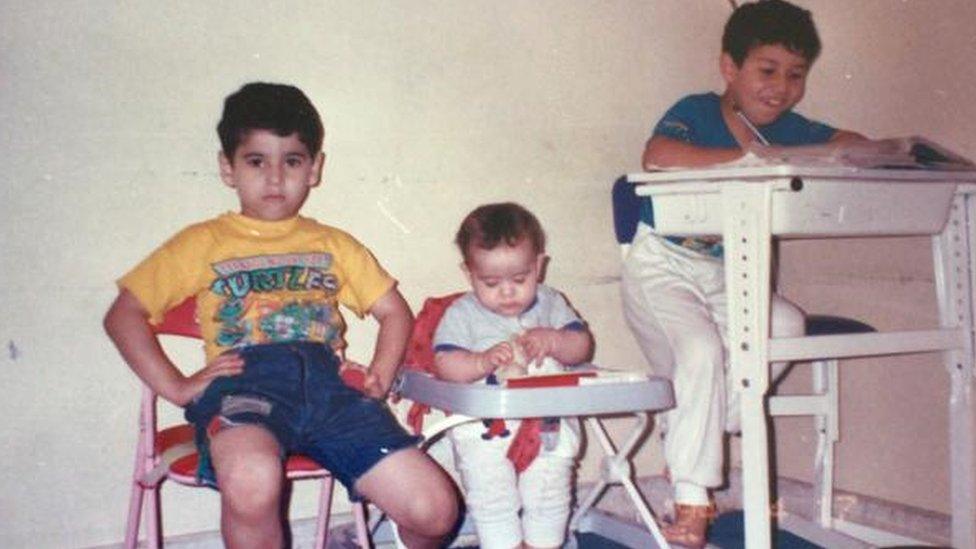

Hamed Amiri, middle, has thanked the NHS for giving him extra years with his brother Hussein, left

The family landed in Austria, where they had been told to destroy their passports.

Hamed did this in the airport toilets, despite some difficulty flushing the plastic cover, meaning he destroyed his boots and emerged soaking wet, much to his brothers' amusement.

They approached a desk and said the only word they had been taught to say: "Refugee", and were taken to an Austrian camp.

"That was the first time I felt like I could be a child again," Hamed said.

They were then transported with other refugees to Germany, but when their handler stopped for petrol he pulled out a gun and demanded their money and they were left with nothing.

It was the second time the family had been robbed - the first being in Moscow.

'I fell into a stack of tyres and got stuck like that'

Mohammed called a friend he knew in Germany, who allowed them to stay in his flat and work in his shop until they were able to get back on the road, where they were trafficked in a lorry through Belgium to Holland.

"You would wait in a ditch and the lorry would pull up, you'd be given a nod and go up a ladder and cut a hole in the plastic sheet, said Hamed.

"But the lorry started moving before I was in and I started to fall off. I thought 'that's it, they're going to go without me' as I was falling but then my dad dragged me on.

"I fell head on into a stack of tyres and got stuck like that, my brothers were laughing."

But the family were caught at the French border after the rip in the lorry was spotted and were taken to a camp in Calais.

Their second attempt to get to the UK, in a 2.5m container a similar size to an American-style fridge, was uncomfortable for the family of five, but successful.

"I remember my brother threw up, the air was not clean and we were in there for a day and a half," added Hamed.

They emerged in Kent, on a motorway, when the lorry driver discovered them.

"He was confused and scared, but he told us to get out and looked the other way," said Hamed.

They stood, stranded, in the middle of the motorway.

"That was my first experience of the UK, and I said 'dad they're so friendly here' because all the cars were beeping at us.

"Now I know they were saying 'what the hell are you doing in the middle of the motorway', but in my head I thought 'they're so friendly, this is really good'."

Hamed said the family was in awe of his mother's plight to improve women's rights in Afghanistan

The family sought out a police officer and were put in a cell while they were processed, where they all fell asleep.

"We woke up to empty trays and my dad said, yeah they were just empty, actually he'd just been munching the food."

The family was processed by authorities, granted asylum and sent to live in Adamsdown, Cardiff, where the focus became getting medical help for Hussein.

'I lost faith in people'

After the robberies during their journey from Afghanistan, Hamed found he had lost faith in humanity and acted out at school, failing his GCSEs and A-levels.

"I thought anyone who was trying to be helpful had an agenda," he said.

But when Hussein was offered a complex 14-hour procedure to fit a valve and pacemaker in his heart, which had a 60% chance of success, he told Hamed he was going to have the surgery because he wanted to finish his degree and have a life.

"That was the moment that changed my mentality," Hamed said.

"The things I was complaining about, integration, racism, language, my brother was the same as me but he hasn't just got those problems, he's got this ticking bomb in his chest."

Hamed managed to secure a place at university and graduated with a 2:1 in computer science, and he works for a solicitors' in Cardiff - while on the side coaching school children about mental health and not to feel held back by race.

Hussein's operation was successful and he went on to become an NHS board member - advising on mental health and measures to make the hospital experience better for young people and their families.

But his health began to deteriorate in 2017, and he was told he would need a heart and liver transplant.

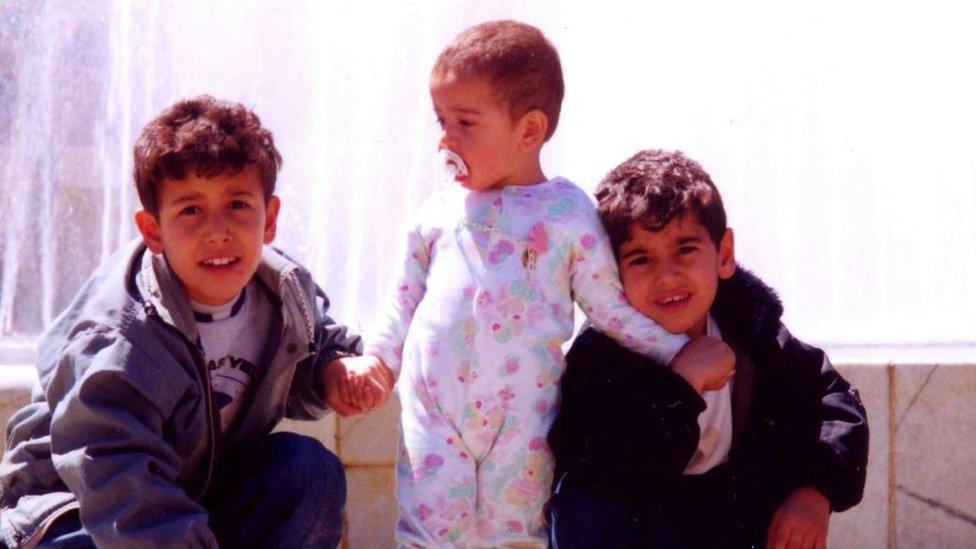

The brothers with some of the NHS staff who helped Hussein

"I believe he would have been the first in the UK to have both [transplants] at the same time, even his own doctor said 'don't do it'," said Hamed.

But as plans were being drawn up in 2018 on how the surgery would be managed, Hussein's health took another turn.

"It was just another visit [to University Hospital of Wales], my grandad had passed away five days earlier and my mum was trying to hide that from him, because emotions could trigger an episode.

"We had a Subway, we had nachos and a sibling argument like we always do, then I got a call at 2am saying 'can you come in?'."

Hussein's heart rate had dropped to between 50 and 60 beats per minute, and his pacemaker was functioning but not bringing it up again.

"That's the only time my dad hasn't needed something translated, because we could sense what the doctor was going to say and I remember those words... 'There's nothing we can do. I think his heart's just had enough'."

Hamed told his mother to look away as her oldest son, Hussein, drew his last breaths

After spotting that Hussein's oxygen level had dropped, Hamed told his mother not to look.

"I had this sense this was it. I had a final lock of eyes with my brother as he took his last breath."

There were about 40 members of hospital staff in the waiting room hoping to pay their condolences to Hussein, who was so well-known for his NHS work, so Hamed showed them in in pairs, for 30 seconds each, to pay their respects.

Since then, hospital staff have raised money to make the changes to hospital environments that Hussein had suggested in his work - such as gym bikes and game consoles in waiting rooms.

Hamed Amiri uses his own experiences to coach children not to feel held back by race

"If we hadn't have come to the UK, I wouldn't have had my brother for as long as I did. It gave us several more years to have those memories and laughter and crazy moments."

Describing his book, The Boy With Two Hearts, as a "love story to the NHS", Hamed added: "With Covid-19, people have started to realise what those front-line workers do for us.

"Our religion and culture and race didn't matter, we were just people that needed help.

"He was the boy with two hearts. He didn't actually have two hearts, I should clarify, it's a metaphor for who he was as a person.

"He had a faulty heart but he had a heart that was so much bigger than anyone could know."

The Boy With Two Hearts will be published on 18 June and featured as BBC Radio Four's Book of the Week from 29 June. Work is ongoing to turn the book into a play at Wales Millennium Centre in November 2021.

- Published23 July 2017

- Published8 July 2016

- Published1 April 2015