Black Lives Matter: The numbers behind racial inequalities in Wales

- Published

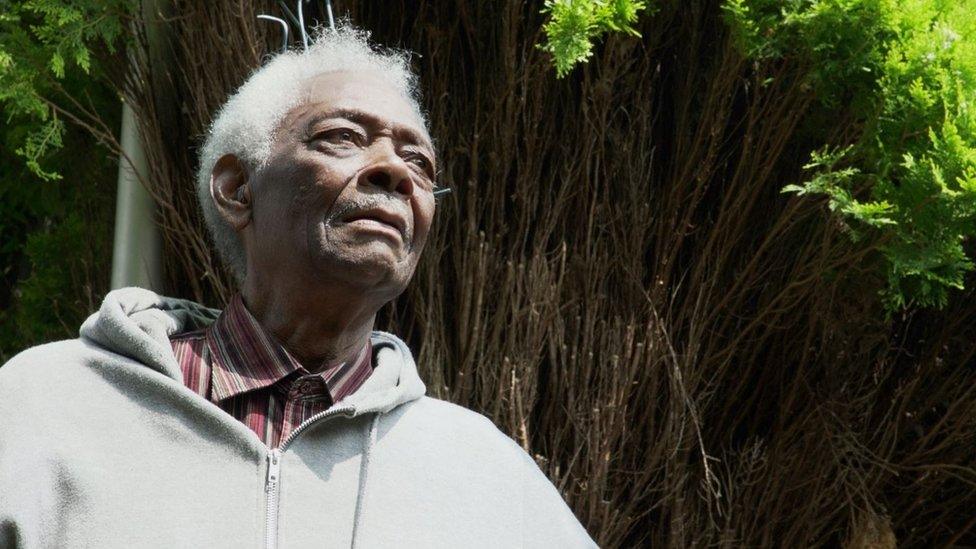

When Neville Howard arrived in the UK in 1947 society was very different

It was an act of defiance that started on American football fields but has reached Wales.

In front of Cardiff City Hall, dozens of people silently "took a knee".

They stayed that way for eight minutes and 46 seconds - the time it is said George Floyd spent with a policeman kneeling on his neck.

Some raised their fists and held banners proclaiming "Black Lives Matter."

Many similar gatherings have taken place around Wales in recent weeks.

Statistics show black, Asian and minority ethnic people (BAME) face inequality in many aspects of life in Wales.

Black people are six-and-a-half times more likely to be stopped and searched by police in Wales than white people.

They are also four-and-a-half times more likely to be arrested.

BAME people have lower employment rates and higher rates of economic inactivity than white people.

The gap is narrowing. But there are higher poverty rates in families where the household's head is not white.

What is 'taking the knee'?

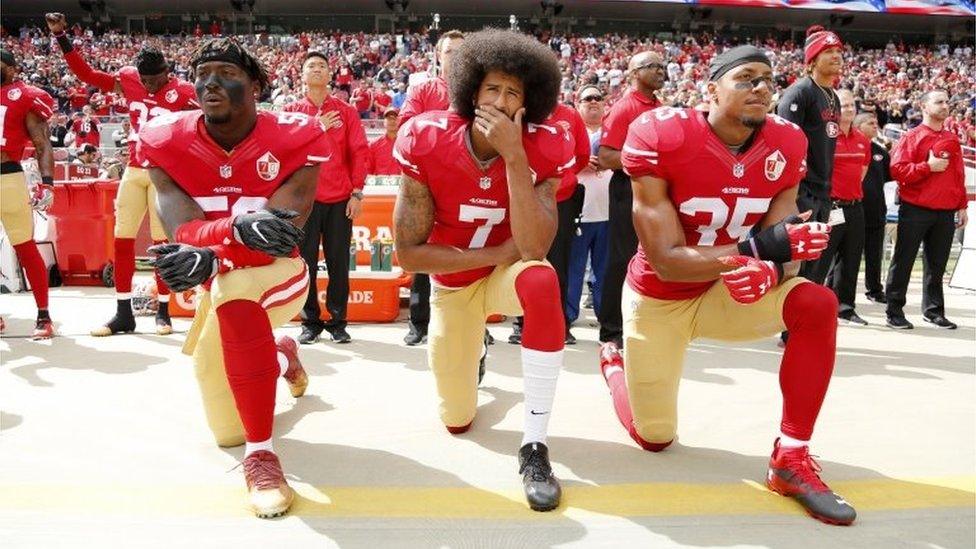

Colin Kaepernick (C), Eli Harold (L), and Eric Reid (R) taking the knee in 2016

American football player Colin Kaepernick first sat on the bench during the national anthem to protest against police brutality and racism - but this developed into kneeling in September 2016, generating US media attention.

Kaepernick said at the time: "I am not going to stand up to show pride in a flag for a country that oppresses black people and people of colour."

Kaepernick and team-mate Eric Reid were later joined by a number of other players, before a rule was introduced - later removed - that teams would be fined if players refused to stand for the anthem.

The gesture has since spread to other sports and protests around the world and has been frequently adopted during protests following the death of George Floyd.

At Cardiff City Hall, some cited the injustice of the coronavirus pandemic as a factor behind protests.

It has claimed a high number of deaths among BAME people.

Lockdown gave people "more time to read about things", said Stand up to Racism Cardiff's Hussein Said.

But "the main thing" was the disproportionate effect on BAME communities.

Statistics show black and minority ethnic people face inequality in many walks of life in Wales

Mr Said did not want protests to be "tokenistic."

"We are trying to make demands and put pressure on people who should really be doing things," he said.

One demand is the removal of Sir Thomas Picton's statue from City Hall.

Once a celebrated war hero, his legacy is being reassessed because of his brutality while governor of Trinidad.

'We've just had enough'

Law student Marwah Ahmed wants the school curriculum to include black history

Law student Marwah Ahmed wants the school curriculum to include black history.

"The only thing I learned was, we were slaves, that's it," the 18-year-old said. "Nothing else."

She said young black people in Wales dealt with racism "every day" and speaking up about institutional racism meant being "made to sound like we are crazy".

"Now it's blown up on social media, people are aware of it, people are educated about it," she said.

"And we've just had enough and we are here to speak out against it."

'Piled up'

Elbashir Idris said there were "systematic inequalities" in many institutions

Elbashir Idris, 24, said: "We really do feel the systemic inequalities.

"Be that from crime and policing, educational inequalities, healthcare, mental health, a lack of opportunities given to those in BAME communities.

"People from BAME backgrounds feel small micro-aggressions that have eventually piled up to the protests we've seen today, on top of police brutality."

'They had notes, I had coins'

Singing pensioner Neville Howard sailed from Jamaica to the UK aboard the Almanzora

Neville Howard is well known for singing in a bass voice around Cardiff.

The 92-year-old arrived in the UK from Jamaica in 1947.

He said equality in Britain was "maybe a bit better" than when he arrived.

"All of us over here with colour at the time were taken advantage of," he said. "And that hurt me.

"But after that, it was no good getting ill by carrying a chip on my shoulder."

Mr Howard sailed on the Almanzora which brought migrants to Britain the year before Windrush.

He remembered "no blacks, no Irish" signs in windows and being paid less than white workmates.

"They had notes, I had coins," he said.

- Published17 June 2020

- Attribution

- Published17 June 2020

- Published9 June 2020