Coronavirus: The story of Wales' 100 days of lockdown

- Published

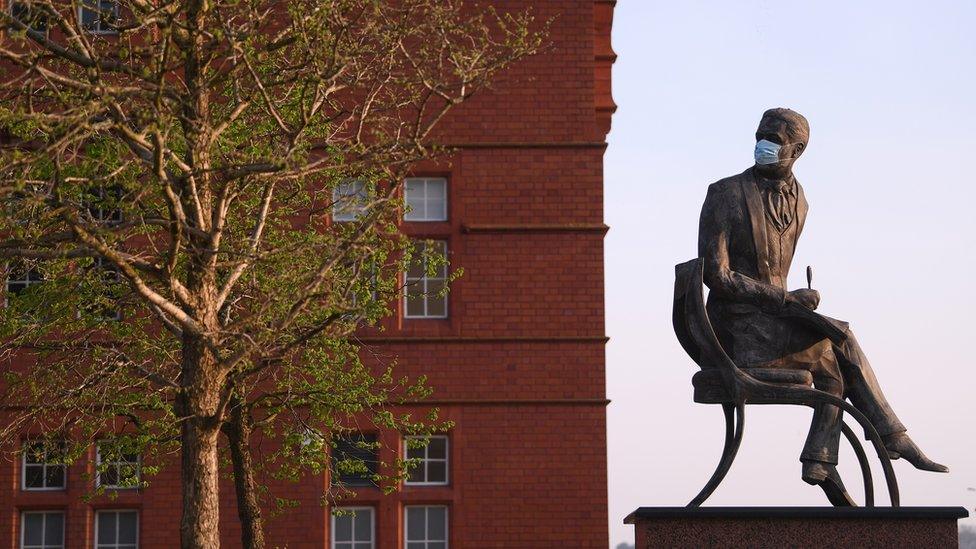

Facemasks are now a common sight in day-to-day life

Wales is now 100 days into lockdown after the outbreak of the global coronavirus pandemic.

It was 23 March when Prime Minister Boris Johnson - and his counterparts in Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland - announced unprecedented restrictions.

Businesses and schools closed, millions of employees were furloughed and - for those who were not - working from home became the new normal.

So what has happened in the first 100 days of lockdown?

What happened on day one?

A series of measures - described as "unprecedented in peacetime" - came into effect on 23 March which saw all High Street shops closed, except those selling food and essential items. Pharmacies, banks and post offices were also permitted to stay open.

First Minister Mark Drakeford urged people in Wales to go out just once a day to shop for basic food and to exercise close to home.

All social events, as well as gatherings of more than two people in public, were banned.

When did the first coronavirus death happen in Wales?

The lockdown came exactly one week after the confirmation of the death of the first person in Wales with Covid-19.

The 68-year-old, who had underlying health conditions, died in Wrexham Maelor Hospital.

This came just over two weeks after the first confirmed case. On 28 February, chief medical officer Dr Frank Atherton said the adult - linked to Swansea's Bishop Gore School - contracted the virus in northern Italy.

There have been 2,408 deaths involving coronavirus in Wales, up to 19 June.

New powers in response to crisis

The Senedd has been mostly empty for three months as politicians carry out meetings remotely

Less than 24 hours into lockdown, Welsh ministers were given a host of new powers in a bid to tackle coronavirus.

Politicians in the Senedd passed a motion giving their consent to the law without a vote, which meant authorities could take people into, or keep them in, quarantine, curb or ban mass gatherings and close premises.

Clap for Carers is born

Wales claps for carers for the 10th and final time

At 20:00 on the first Thursday of lockdown, a tradition began that would involve millions of people up and down the country - Clap for Carers.

Thought up by Annemarie Plas, who was inspired events in her home country of the Netherlands, it saw people take to their doorsteps, windows and balconies to clap their hands and bang their pots and pans to give a boost to the people working on the front line.

The final weekly clap was held on 28 May after Annemarie herself said it would be "beautiful" to end it after 10 weeks.

As it turned out, this was not the end - people have been asked to take part in an annual Clap for Carers, starting on 5 July - the 72nd anniversary of the creation of the UK's National Health Service.

First hotspot emerges

In the early days of the pandemic, one corner of Wales earned the unwanted title of the country's hotspot.

Aneurin Bevan health board, which covers the old county of Gwent in south east Wales, recorded 358 cases by 26 March and there were fears the area could be "following Italy".

It had more than double the number of cases of any other health board, although that trend did not continue and the latest stats show two other health board now have more cases.

Testing target abandoned

In April, the first minister admitted coronavirus testing had not "been good enough" after a drive-in testing centre for key workers was shut on Easter Monday - a move that one politician said "beggars belief".

Just one day after admitting this, the Welsh Government faced more pressure after it scrapped its target of 5,000 tests a day by mid-April with Mr Drakeford himself calling parts of the plan unachievable.

No new targets were set after this date - at which point the Welsh government only had the capacity to do 1,300 tests a day at most.

Plaid Cymru called the move a "scandal", while the Tories accused ministers of "piecemeal disorganisation".

'I could've sworn I turned my mic off'

Remember - if that line isn't through your microphone logo - everyone can hear you

Ministers - much like the rest of us - have got very familiar with the Zoom video-conferencing app during lockdown, but for the man at the forefront of Wales' fight against coronavirus, one virtual meeting made headlines for all the wrong reasons.

Health Minister Vaughan Gething had to apologise to his Labour colleague Jenny Rathbone after he was caught swearing about her after forgetting to turn his microphone off.

"What the [expletive] is the matter with her?" he said, much to the amusement of several of his colleagues.

Health board fails to properly report deaths

Wales largest health board, Betsi Cadwaladr, was criticised after it failed to report its daily cases.

On one Thursday, it announced 84 deaths in one go, making it seem as though Wales had seen the biggest daily jump in confirmed deaths, but it actually included Betsi's figures for a whole month.

This was followed four days later by a second health board - Hywel Dda in west Wales - admitting it had under-reported its deaths by 31.

Past the peak

May brought some good news as Mr Drakeford said the peak of the virus had passed, heralding the news the first relaxation of lockdown rules could begin, almost two months after they were imposed.

Subsequently, people were allowed to exercise outside more than once a day and some garden centres began to reopen.

Wales and England take different roads

Sign of the times - Wales and England have had different rules in place since May

For the first six weeks of lockdown, Wales, England and Scotland all took the same approach with the message "stay at home, protect the NHS, save lives".

This changed on 10 May when England shifted to a message of "stay alert" as the UK government allowed people to travel further and spend more time outdoors.

However, Mr Drakeford urged people in Wales to still stay home "wherever you can".

Only from 1 June were people in Wales allowed to meet with friends or family from another household, but they were still urged to stay within five miles of their home.

Back to school

June saw some glimmers of normality return, including professional sports being allowed to resume, the announcement schools would reopen at the end of the month and how a post-coronavirus Cardiff city centre would look.

With England and Wales now having different rules and restrictions in place, one Welsh minister attacked his Westminster counterparts, saying the UK government had "given-up" on a science-led approach to coronavirus.

This came after England's easing of lockdown before Wales led to confusion, with police in one area of Wales having to turn away 1,000 cars in just two days. Officers said many of the people they spoke to claimed not to know they were breaking the law.

Factory outbreaks see spike in cases

The end of June saw outbreaks of coronavirus at three different meat and food factories.

2 Sisters on Anglesey has had 210 confirmed cases, with Rowan Foods in Wrexham reporting 166.

Kepak in Merthyr Tydfil has told household contacts of the 130 of its workers who have tested positive to self-isolate.

What next?

Hugs - remember those?

On Monday, Mr Drakeford announced that families from two different households would be allowed to spend time in each other's homes as of 6 July.

People must choose and stick with one other home, which cannot be changed once arranged.

It follows similar "support bubble" schemes elsewhere in the UK.

So cooking, exercising and even hugging are now back the agenda for families as Wales, like the rest of the world, takes slow but steady steps towards a normal life once again.

The most obvious political theme of the past 100 days has been the divergence in the four nations' approach to this crisis.

The difference in approach between governments in Wales and England caused confusion at times, but it also did more than any other event in the past 20 years to increase people's understanding of devolution.

It has also raised the profile of the first minister and Welsh Labour leader, Mark Drakeford, who had previously been struggling for visibility among Welsh voters.

This matters because there's a Senedd election looming next May and an election is always the acid test in politics.

Irrespective of how well or badly they think Mr Drakeford's government has handled the crisis, can we expect to see a higher turnout?

In the 20 years of devolution in Wales, fewer than half of eligible voters have taken part in Senedd elections. This time around, voters know how much power Welsh ministers have over their daily lives, so will more of them want a say in deciding who to give that power to?

A SIMPLE GUIDE: What are the symptoms?

AVOIDING CONTACT: Should I self-isolate?

LOOK-UP TOOL: Check cases in your area

MAPS AND CHARTS: Visual guide to the outbreak

- Published27 September 2020

- Published27 June 2020

- Published25 June 2020

- Published11 June 2020