Coronavirus pandemic: Coma patients coming home to 'different world'

- Published

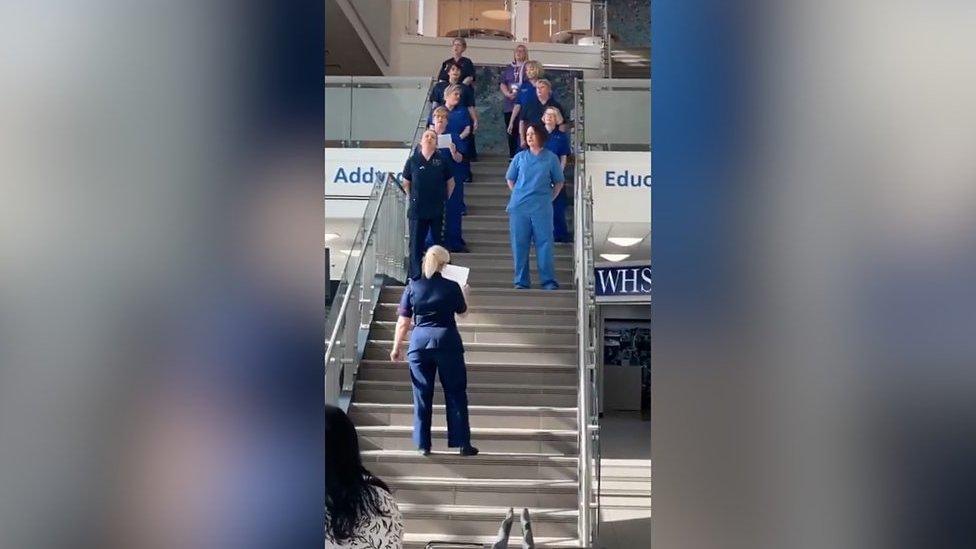

Callum Fleming feels he would be bedbound if it were not for the scheme

Intensive care patients who were seriously ill or in comas during the coronavirus pandemic have been coming home to "a different world".

Some are dealing with "survivor's guilt" after realising they lost loved ones.

And others wanted to do normal thing such as watching football while they recovered, only to find the country was in lockdown.

A "unique" scheme has now been extended to help them.

Funding was granted for the Swansea Bay health board area scheme just before the pandemic, and those who have been ill with Covid-19 can now access the support too.

Anyone who has been in intensive care for more than three days is offered hydrotherapy at Morriston Hospital, and can take part in community-based exercise programmes.

The same team provides physiotherapy in the intensive therapy unit (ITU), on the ward and at home - and a patient said the continuity of care made a huge psychological difference.

'There was no football'

Karen James, manager of the critical care and surgical physiotherapy team, said: "Everything had changed.

"Before, they may have wanted to watch a football match on the TV - except now there was no football.

"Sadly, we've also had quite a few patients who have lost important people, because Covid tended to affect families.

"That's a huge aspect of it. You get a little bit of survivor guilt, as well as the consequences of the horror they went through."

Ms James said that, if the service had not already been agreed, patients would not have been seen for three months or had any support after going home.

Among those helped is Callum Fleming, 26, who became so unwell with pancreatitis last September that he was put on life support and into a coma.

Callum Fleming was in a coma for six weeks

"I woke up six weeks later and didn't really know what was going on," he said.

Callum, a carpet fitter from Port Talbot, described the period as "a big blur", spending three months in hospital and receiving physiotherapy before returning home last December.

His condition deteriorated in February and when the pandemic struck, he was struggling to get up the stairs. But treatment and hospital appointments were cancelled and at first he felt abandoned.

During lockdown, while he shielded, Callum's family tried to help by repeating physiotherapy exercises with him, but he suffered mentally and physically.

"I would stay in bed just because it got so difficult to get about, to get down the stairs," he said, adding he believes he may be bedbound now if he had not received help.

His father Keith said when physiotherapists started visiting, it was like "a light had been switched on in the house".

Ms James said: "When you have a heart operation, you have cardiac rehab, you will get a programme explaining everything.

"But there are no services post-ITU because we have such a diverse group of patients.

"We could have everything from an 18-year-old who has been in a car crash to a 75-year-old with chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder, so we can't put them in groups of rehab."

Psychological problems 'higher' for Covid-19 patients

In the past, patients would not be seen until three months after they left hospital and only then be offered a six-week rehabilitation programme.

"But you hear of the devastation people have when they first get home, how they can't get up the stairs, how they're having to live downstairs, how they won't go out of the house," Ms James said.

"That led us to think about having a team that would follow them from ITU onto the ward, give them a little bit of extra rehab on the wards and then follow them home."

However, when the scheme was devised, nobody had any idea a large number of patients would be those who had battled coronavirus.

Ms James said many progress "remarkably quickly" in the communities, but added: "We are finding that the psychological problems for Covid patients are slightly higher.

"They've had quite a large cocktail of drugs and are paralysed for quite long periods of time.

"We feel there may be more long-term psychological consequences than we would normally expect with some of our ITU patients."

A SIMPLE GUIDE: How do I protect myself?

AVOIDING CONTACT: The rules on self-isolation and exercise

HOPE AND LOSS: Your coronavirus stories

She said there was an expectation the sickest would be the worst, but when someone was "sedated and paralysed" they did not see what was going on around them.

"When you're awake, watching things happen to other people, it can be more traumatic than for those lying there asleep," Ms James said.

"Some people have no recollection at all of being on ITU, others have very lucid times mixed in with the dreams and the visions and the hallucinations they've had because of the medication.

"They have very scary mixed images of what has gone on in ITU.

"Some people come out of it and say, 'it's changed my life, my life is so much better now because I survived this'.

"Other people struggle and feel like they can't get over it."

- Published24 May 2021

- Published16 July 2020

- Published19 April 2020

- Published24 March 2020