Cancer treatment gives terminally ill mother all clear

- Published

"I was told prepare my children for the worst"

A terminally ill cancer patient has been given the all-clear after becoming the first woman in Wales to be given a pioneering treatment.

Helen Wynne Hughes, 32, was given CAR-T treatment that uses the body's own cells to fight cancer.

The mother-of-three, from Denbighshire, had the therapy earlier this year after other treatments failed.

"When the doctor said it was clear... we were in tears. Finally, there was no cancer at all," she said.

Whatever Covid restrictions may be in place this Christmas, it is set to be special for the Hughes family.

It is a world away from a year ago when Helen was making memory boxes for her three young children - Aled, four, Tomos, two, and 19-month-old Beca.

"I had to tell them 'perhaps it is mummy's last Christmas'," she recalled.

"They are so small, it was very hard. Making memory boxes, looking back thinking I might not get to do things with them again."

Helen feared last Christmas would be her last

This festive period will also bring back memories of when this ordeal began.

It was Christmas Eve 2018 when she was told scans had revealed a mass on her chest "the size of a grapefruit".

She had felt unwell during her third pregnancy, only to be diagnosed with lymphoma.

"I was allowed to go home on Christmas Day to see the children open their presents and have lunch," she recalled.

"But I only managed two hours as I was so ill."

Helen, from Ruthin, started chemotherapy almost immediately and 10 weeks later, she gave birth to her "bundle of joy" Beca.

However last autumn she was given the devastating news that the cancer was unresponsive and had spread to her bones, liver, lungs.

"I was told to prepare my children for the worst," she said..

Helen and Elgan were married in 2019 when she was told the treatments were not working

Early this year, Helen was offered a glimmer of hope when she was told she qualified for the new Chimeric Antigen Receptors Cell Therapy (CAR-T) treatment that had just been approved by the NHS.

"CAR-T was the last hope for me. I'd do anything," she said.

Helen and husband Elgan had looked into getting the treatment privately but the estimated £500,000 bill made it "out of our reach".

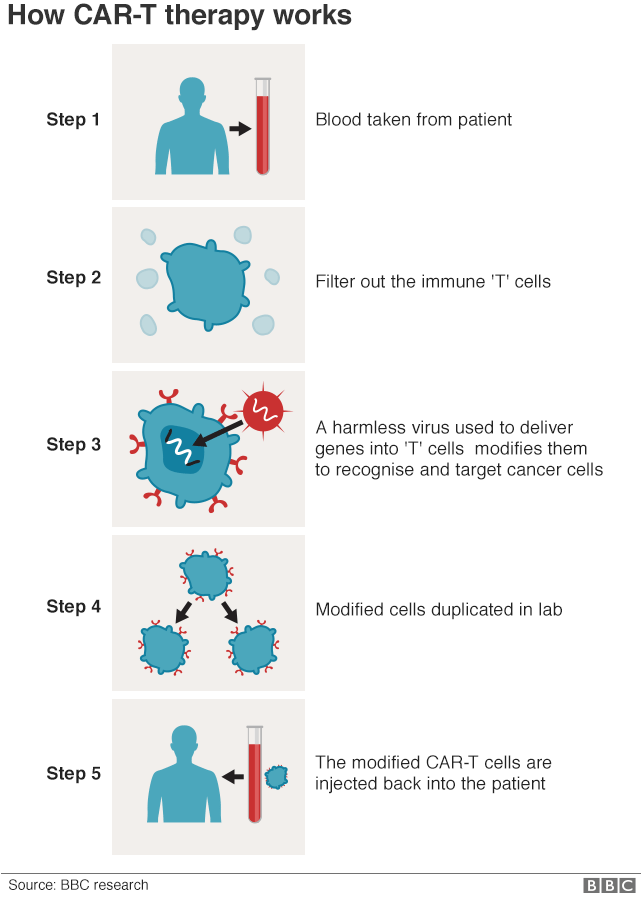

How does CAR-T treatment work?

CAR-T genetically reprograms the immune system to fight cancer.

It is a "living drug" that is tailor-made for each patient using their body's own cells

Firstly, parts of the immune system - specifically white blood cells called T-cells - are removed from the patient's blood, frozen in liquid nitrogen and sent to laboratories in the United States.

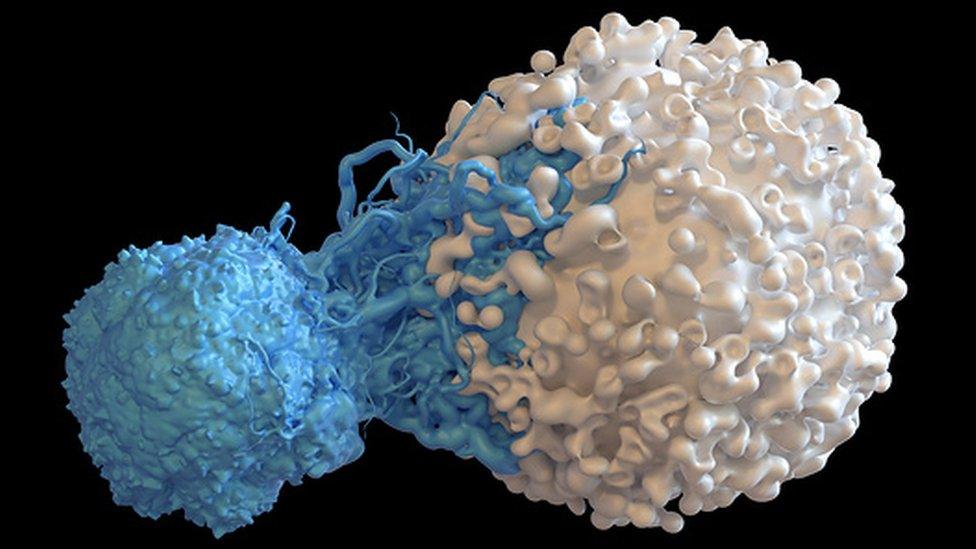

There, the white blood cells are genetically reprogrammed so that rather than killing bacteria and viruses, they will seek out and destroy cancer.

They are now "chimeric antigen receptor T-cells" - or CAR-T cells.

Millions of the modified cells are grown in the lab, before being shipped back to the UK where they are infused into the patient's bloodstream.

The whole process takes a month.

As this is a "living drug", the cancer-killing T-cells stay in the body for a long time and will continue to grow and work inside the patient.

Helen spent five weeks in hospital

Helen spent five weeks at The Christie Hospital cancer centre in Manchester when the first coronavirus lockdown had just started.

"There were some quite shocking side effects," she said.

"I couldn't remember who I was, I couldn't eat and I couldn't walk properly but it was all worth it."

The family then faced an agonising six-month wait to learn whether the treatment had worked.

Last week she was finally given the news she had craved, that the cancer "had all gone".

Helen Wynne Hughes was diagnosed with lymphoma while pregnant with daughter Beca

"I was prepared for the worst but luckily CAR-T has saved my life," she said.

"I feel quite proud being the first female from Wales to have the treatment and hopefully many more after me will be allowed to have the treatment."

While she still receives monthly blood transfusions because her immune system is "at rock bottom", she is now also looking for a stem cell donor and hoping to go back to work as a primary school teacher later next year.

"The stem cell treatment will hopefully mean the cancer can't return," she said. "So I'm looking for a match."

- Published20 January 2020

- Published21 June 2019

- Published31 January 2019