Conjoined twins Marieme and Ndeye settling at Cardiff school

- Published

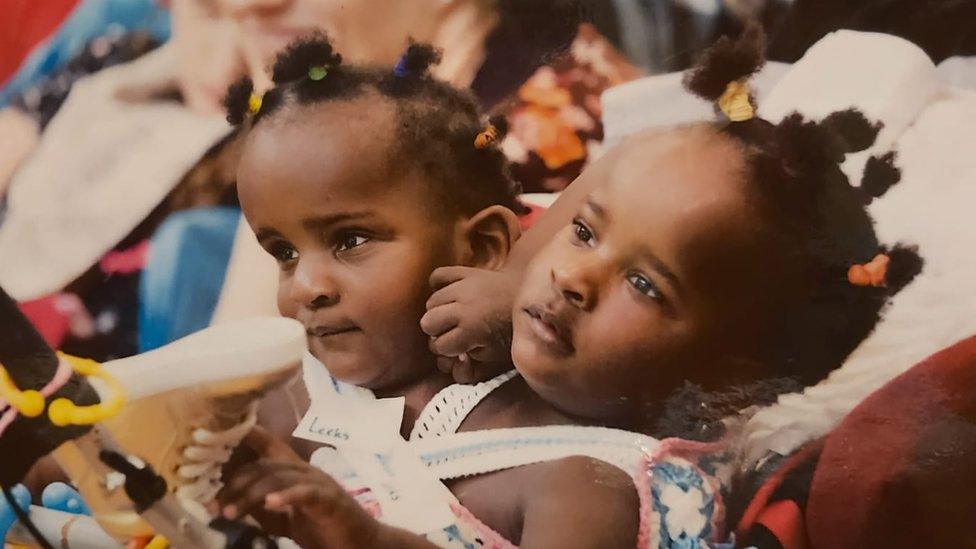

The twins' father says what they have achieved is a 'herculean achievement'

Conjoined twins who were expected to die within days when they were born are nearly four years later said to be settling in at their Cardiff school.

Marieme and Ndeye Ndiaye were brought to the UK from Senegal in 2017 by their father Ibrahima for treatment at London's Great Ormond Street Hospital.

The girls, now four, are learning to stand and their father said their progress was "a Herculean achievement".

Their head teacher said the girls had made friends and were "laughing a lot".

The girls, who have separate hearts and spines but share a liver, bladder and digestive system, have conditions which put them at higher risk of complications from Covid.

However, Mr Ndiaye said he had wanted them to start school for their development.

"When you look in the rear view mirror, it was an unachievable dream," he said.

"From now, everything ahead will be a bonus to me. My heart and soul is shouting out loud, 'Come on! Go on girls! Surprise me more!'."

Mr Ndiaye brought the girls to the UK through funding from a charitable foundation run by Senegal's first lady Marieme Faye Sall, before he sought asylum.

In March 2018, the family were moved by the Home Office to Cardiff as asylum seekers can be moved anywhere in the UK and they now have discretionary leave to remain.

In 2019, Great Ormond Street surgeons considered attempting separation but it was something Mr Ndiaye did not want because of the risks involved.

The girls have such complex circulatory systems medics now believe they would not survive being separated

Since then, doctors have found the girls' circulatory systems to be more closely linked than previously thought and neither would survive without the other, making separation now impossible.

The girls' head teacher Helen Borley said they were learning well since starting reception in September and had made new friends.

'Different characters'

She said: "Children either say, 'I'm Marieme's friend' or 'I'm Ndeye's friend' - they don't say, 'I'm the twins' friend'. Children very much identify as being one person's friend or another - because the girls are very different characters.

"They are laughing a lot - which is always a good sign, isn't it? Any child that is laughing a lot is a happy child."

Marieme receives oxygen from Ndeye's stronger heart and food via their linked stomachs

For the twins, school needs to fit around hospital visits.

In October, the girls needed surgery at Great Ormond Street Hospital.

Dr Gillian Body, a paediatric consultant at the Children's Hospital for Wales in Cardiff, said the procedure was important, despite the risks.

She said: "The girls have complex anatomies and that makes them prone to infections and potentially sepsis.

"One of the challenges we had was getting antibiotics into them quickly, and this tube or cannula they've had fitted, means we can get them into them more quickly with less distress to the girls."

The girls have been experiencing the feeling of standing, at children's hospice Ty Hafan

She said Marieme's heart was complex with lots of abnormalities that cause her problems with doing exercise and can lead to breathlessness.

'Finding that balance'

At children's' hospice Ty Hafan in Sully, Vale of Glamorgan, the girls have been learning what it feels like to stand.

A special frame gives them the experience of being upright, helping build strength in their legs.

Physiotherapist Sara Wade-West said it had been hard for them.

"It's a really different sensation when you're used to being sat down, to be upright can be scary," she said.

"To start with, particularly Ndeye wasn't very keen. We try and sneak the therapy in around the play, encouraging them to reach for toys to make them work a bit harder, but if they know it's therapy it's not so fun.

"Because of their cardiac function we can't push them too much so it's finding that balance - challenging them to get stronger but not exhausting them."

The twins' father Ibrahima Ndiaye said they were his "warriors"

Watching his daughters stand is more than just a breakthrough for their father.

"They are showing that they don't only want to live, but be active and play their part in society," he said.

"All these achievements bring light and hopes for the future. But I know how fragile, complex and unpredictable their lives can be."

Mr Ndiaye said his hopes were "parallel to my fears" as the girls had "so many times come close to the worst".

"But the very least I can do for the girls is figure out my hopes for them," he said.

"The most I can do is to be beside them and live inside that hope and never allow anything to take that hope away.

"They are my warriors. They have proved they will never surrender without fighting. It is not yet over."

- Published23 January 2019

- Published5 August 2019