Foot-and-mouth disease: 'Continual worry' for Wales' chief vet, 20 years on

- Published

Looking back at the 2001 foot-and-mouth outbreak

The risk posed by foot-and-mouth disease is a "continual worry" for Wales' most senior vet, two decades on from the last major outbreak.

Christianne Glossop said 2001 was a year of terrible memories she will "never forget".

Across Wales a million animals were slaughtered, with farming and tourism thrown into crisis.

There are now "solid contingency plans" to minimise the chances of such widespread infection, she explained.

Appointed chief veterinary officer for Wales in 2005 when powers over animal health and welfare were devolved, at the time of the epidemic Prof Glossop was working in private practice.

The first case was detected at an abattoir in Essex on 19 February 2001.

"Everybody involved in agriculture would remember exactly where they were and what they were doing on that dreaded day," she said.

Within a week, the virus had reached Anglesey.

Powys and Monmouthshire were also to become among the worst-hit counties.

Christianne Glossop recalls how farmers cried in her arms when she told them their pigs were infected

Distressing scenes of billowing smoke from burning pyres and carcasses being buried in vast pits filled TV news bulletins in a year consumed by efforts to get the outbreak under control - at an estimated cost of £8bn to the UK.

Footpaths were closed, tourism nosedived, major events such as the Royal Welsh Agricultural Show and the Urdd Eisteddfod were cancelled and a general election delayed.

Highly infectious, foot-and-mouth disease causes fever and painful blisters inside the mouth and under the hooves - and can be fatal for young animals.

For Wales' farmers the fact the 20th anniversary of the crisis coincides with current lockdown restrictions has brought often traumatic memories to the surface.

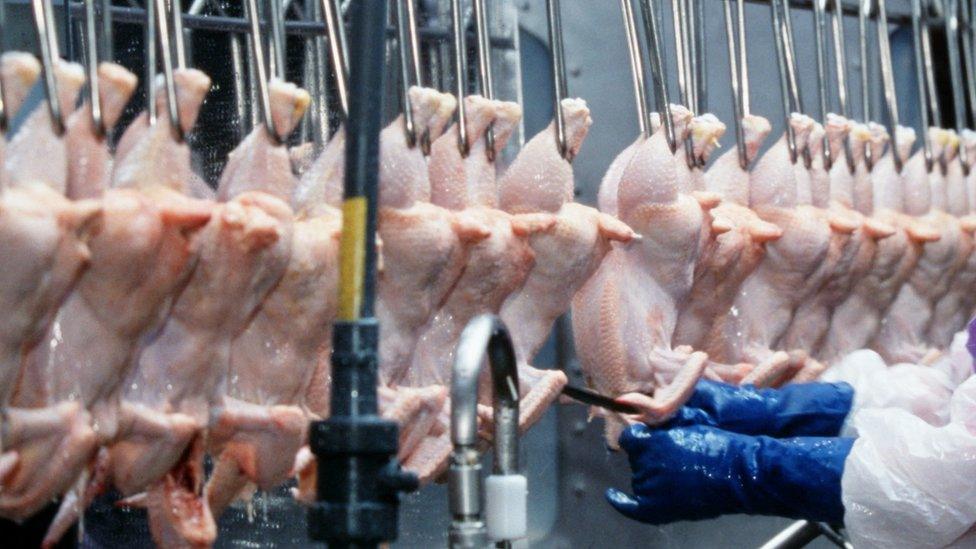

Foot-and-mouth disease caused widespread disruption throughout the UK in 2001.

"What was very sad and emotional was watching the animals being slaughtered on the farms and then being burnt and the smoke afterwards. It was something that sent a shiver down your back really," said Gareth Davies, who runs an upland farm in Cwmgwilym, north of Brecon in Powys.

His sheep and cattle were shot after signs of infection were found on a neighbouring farm.

"One day you've got a farm full of livestock and the next day it's empty, like a graveyard," he said.

Twenty years ago livestock across the UK were being burned

"It's a real shock - because we live with these animals, they're part of us - we have a respect and a loyalty and an affection for them.

"It's no different to the average person in the street with their pet dogs - it's the same emotional feeling you have."

Sheep were being tested in the Brecon Beacons in 2001 in an effort to control the spread

Prof Glossop recalled visiting a pig farm and having to break the news it had been hit by foot-and-mouth to the farmer and his two grown-up sons.

"We stood in the farmyard and these men, they cried in my arms. It's not something you can ever forget."

Lessons learned from that time mean Wales and the UK are better placed to respond in future, she believes, pointing to a smaller outbreak in 2007 in Surrey that was quickly contained.

"A lot of things have changed since 2001. I do believe the plans we have in place are much tighter now, they're more robust and we know what to do."

Systems for registering and tracing livestock have improved, particularly for sheep and pigs, so the authorities know where they are.

A six-day standstill rule limits movement of animals on and off farms to allow time to spot signs of disease and prevent its spread.

A UK-wide movement ban would also be introduced immediately in the event of a new outbreak - unlike in 2001 when a delay of several days was blamed for making the situation worse.

Anglesey was the first place in Wales to have a positive test in 2001

Prof Glossop believes the devolution of animal health and welfare powers is another step forward, meaning Wales can tailor its own plans to the nature of the farming industry in the country.

"We have a close working relationship with our farmers and our vets - we can call people together and share messages quickly and widely. I sleep with my phone by my bed and any time of day or night somebody out there could be seeing signs of a notifiable disease."

Joint exercises are also carried out across the four UK nations - the last, codenamed Blackthorn, taking place in 2018.

Stephen James, chair of the Welsh Government's animal health and welfare framework group, said it was "so important everyone sticks to the rules".

"This applies if you keep hundreds of animals or even just a single pig behind your house - you mustn't keep it under the radar."

John Mercer says a risk remains from illegally imported meat

Strict border controls are also vital, according to John Mercer, who worked for the state veterinary service at the time of the epidemic and is now director of the NFU Cymru farming union.

It is thought one way the virus could have reached the UK in 2001 was through illegally imported meat, leading to a ban on feeding animals with any catering waste or kitchen scraps.

"We have excellent protocols in place to stop anything coming in via the legal trade but there's always a risk when it comes to the illegal trade as we know foot-and-mouth is endemic in some parts of the world," Mr Mercer explained.

'Healing'

The events of 2001 had "really pushed people to the edge", he said. "Let's hope we never see that again."

Wales' final case was identified in Crickhowell, Powys on 12 August 2001, with the country declared free of foot-and-mouth disease in December that year.

Slowly the countryside returned to normality, which Prof Glossop describes as a "healing in people's hearts and a healing in the land".

- Published23 January 2020

- Published24 October 2017

- Published8 June 2020