Covid and sleep: 'Why can't I sleep and why are my dreams so vivid?'

- Published

It's 3am and you're wide awake in bed, thoughts racing.

You've counted valleys of sheep, drank chamomile tea and sprayed lavender mist on your pillows.

You've tried everything - even Google. So why are you still struggling to sleep?

The answer could lie in your anxiety about the Covid pandemic, psychologists say, and this could be stopping you from sleeping - or giving you crazy dreams.

Why can't I sleep at the moment?

The pandemic and lockdowns have made it harder to maintain routines and to fall asleep, with many people reporting feeling more anxious than usual, according to a survey by the Sleep Charity, last April.

Vicki Dawson, the charity's chief executive, said working from home and socialising on screens has had a huge impact on sleep, as well as worries about health and finances.

"There is a link between screen activity and having difficulty nodding off at night," she said.

"Screens are really stimulating and also there is some thought that they may suppress melatonin, which is the sleep hormone that we produce when it's dark, because the screens are essentially a light source."

Emeritus professor of clinical neuropsychology and trustee of The Brain Charity, Gus Baker, said the stress and anxiety associated with the pandemic has disrupted our "sleep architecture".

"When we're not in a pandemic, we would normally be going out to work, we'd be exercising, we'd be eating meals regularly, we'd be looking after ourselves and we'd be engaging in social activities," he said.

"What the pandemic has done is to interfere with that... that impacts upon our sleep."

Why am I having such vivid dreams?

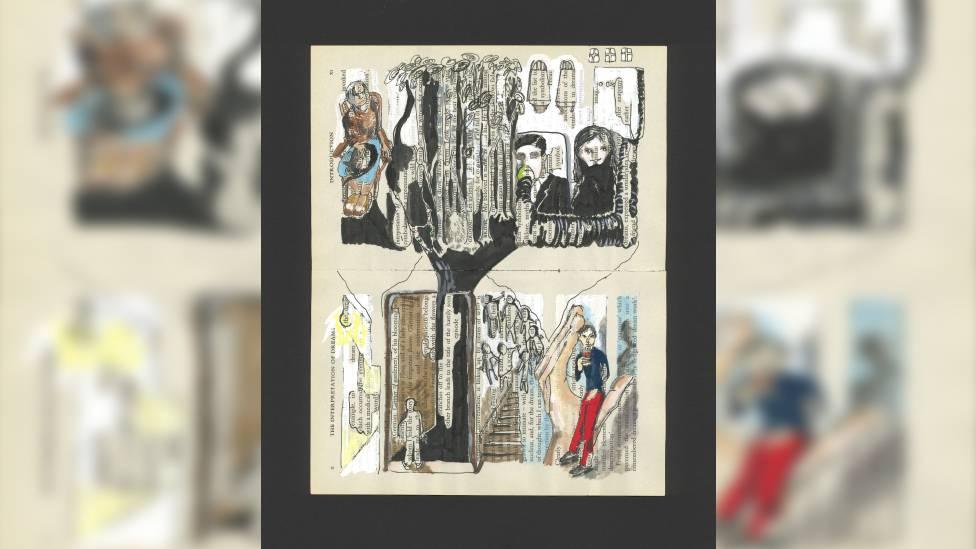

Libby Nolan's nightmare was painted on to extracts from Sigmund Freud's book The Interpretation of Dreams

Libby Nolan, 57, a nurse at a hospital in south Wales, contracted Covid at the start of the pandemic.

Soon afterwards, she began experiencing vivid nightmares.

"I was off sick for 10 weeks and that's when I had the dreams. It's like a recurring dream," she said.

The Covid pandemic gave nurse Libby Nolan nightmares

"[In my dream] I'm at a party or somewhere everyone's relaxed except me and I'm terrified, I'm absolutely terrified. And I'm running round trying to get people to recognise that there's danger and people are ignoring me.

"They know I'm there but they're just ignoring me and I can't get anybody to react."

Later in what she described as a "night terror", Ms Nolan dreamt she ran into another room where there was an old-fashioned ventilator attached to a faceless, long thin body on a hospital bed.

"Breathless with terror," she ran into a room where a large cat covered her face, stopping her from breathing.

Ms Nolan's nightmare is now the focus of Dreams ID, a joint project between Swansea University and University of Wales Trinity Saint David, on dreams during the pandemic, where nine participants told their vivid dreams to psychology professor Mark Blagrove and a global online audience.

Dr Julia Lockheart painted the participants' dreams as they were telling them to the psychologist

Artist and head of contextual practices at Swansea School of Art and University of Wales Trinity St David, Dr Julia Lockheart, painted each dream, which will be exhibited at the Freud Museum London from 19 May to 12 September and at Oriel Science in Swansea from 22 May.

"Mark [Blagrove] said to me, if I tell the dream it will go away - and it has," said Ms Nolan.

She said they had discussed how much anxiety she had faced as a health worker, particularly in the early stages of the pandemic.

"I can't tell you the terror in the hospital - we all thought if we catch it we die... it was really terrifying," she said.

"Nobody was sleeping. Work was so scary and it was hard seeing some of the things, but your team are like your family and you don't want to let them down.

"I wasn't alone. Everyone I spoke to was having really horrible dreams about death."

Prof Mark Blagrove of Swansea University led the study into people's dreams during the pandemic

Prof Blagrove said: "We had nine online discussions with health or key workers in which they would discuss at length a recent dream or nightmare.

"There was a real close connection between the dream and what had been happening to them in waking life."

What happens when we don't get enough sleep?

Experts agree that regular lack of sleep can have adverse effects on our physical and mental health, with research linking it to increased risks of strokes and heart disease.

"Sleep deprivation has a huge impact on every area of life. There's lots of research about how it impacts our mental health and we know from missing a few nights how quickly it takes to feel low in mood, depressed, even anxious, because of that," said Ms Dawson from the Sleep Charity.

"If you're sleep-deprived it's much harder to make decisions and you might be more irritable.

"There's lots of research too around the physical side of things, so our immune systems become compromised if we are sleep-deprived and overly tired, so we tend to pick up things that we perhaps wouldn't have done. There's research on links to heart disease, strokes, obesity, and it's a very depressing picture.

"But if we turn it around and we get healthy sleep, what can that do for us? The benefits are huge, we look better, we feel better, we perform better, it has all sorts of positive knock-on effects, yet we often don't give sleep the priority that it really deserves in our lives."

Prof Blagrove said: "Having at least seven hours is really quite important for people from the point of view of the sleep washing out toxins that are in the brain.

"Research shows there's a risk of dementia for those getting less than six hours of sleep on a persistent basis, over decades."

How to get more sleep

There are a number of ways people can minimise the impact of the pandemic on their sleep patterns, from banning the TV from the bedroom to simply closing the curtains.

"Try to avoid working on the actual bed, because we want the bed to be associated with sleep and not with the workspace," said Ms Dawson.

Prof Penny Lewis says sleep engineering can help improve slow-wave sleep which affects memory, brain health and even susceptibility to dementia

"I would suggest making a clear distinction between using the bedroom for work and using it for sleep and relaxation, like wearing a pair of work shoes, so when you're wearing them you're in work mode and when you take them off you're in home mode."

Prof Baker added that working from home has changed the bedroom from being "a place for sleep and sexual relationships".

"What you need to do is ensure that's what your bedroom is for, so you need to remove any electronic gadgets from your bedroom," he said.

"You've got to create a habit for good sleep... before you go to bed you make sure that you haven't consumed alcohol or coffee or tea or any stimulant for at least an hour or two before you go to sleep.

"Go to bed at the same time each night and try to stay in bed until the same time each morning. You've got to learn how to switch your mind and body off and almost prepare it for sleep."

AUTISM, CORONAVIRUS & ME: Dan’s top tips for coping with Autism during a pandemic

TALKING IS KEY: Paralympian Aled Sion Davies: 'I didn’t even know mental health was a thing'

- Published18 February 2021

- Published27 February 2021

- Published9 October 2020

- Published26 May 2020

- Published15 March 2024

- Published15 March 2019