Olympics: Headstone bid for champion in unmarked grave

- Published

Cecil Griffiths is Wales' youngest Olympic track and field gold medallist

He is one of Britain's youngest ever Olympic champions but Cecil Griffiths died in poverty, so much so he was laid to rest in an unmarked grave.

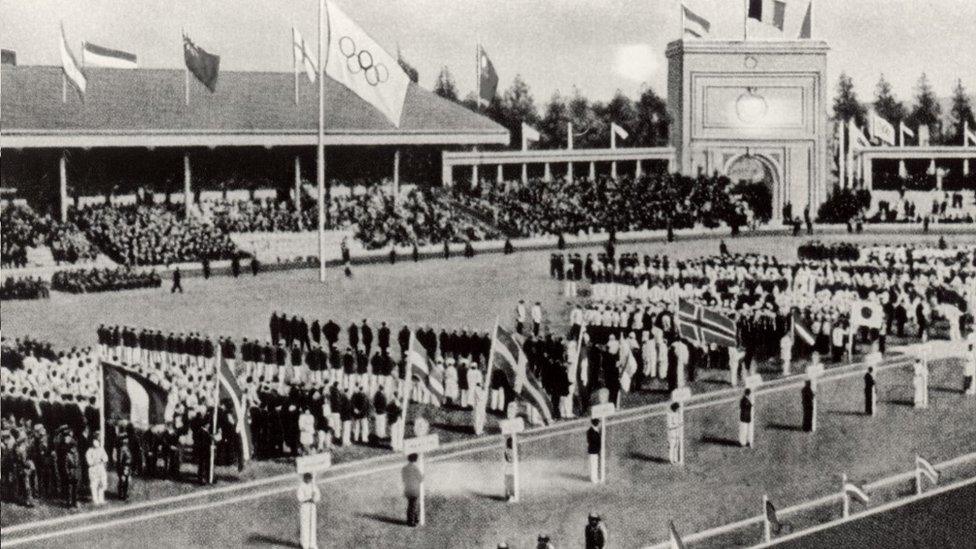

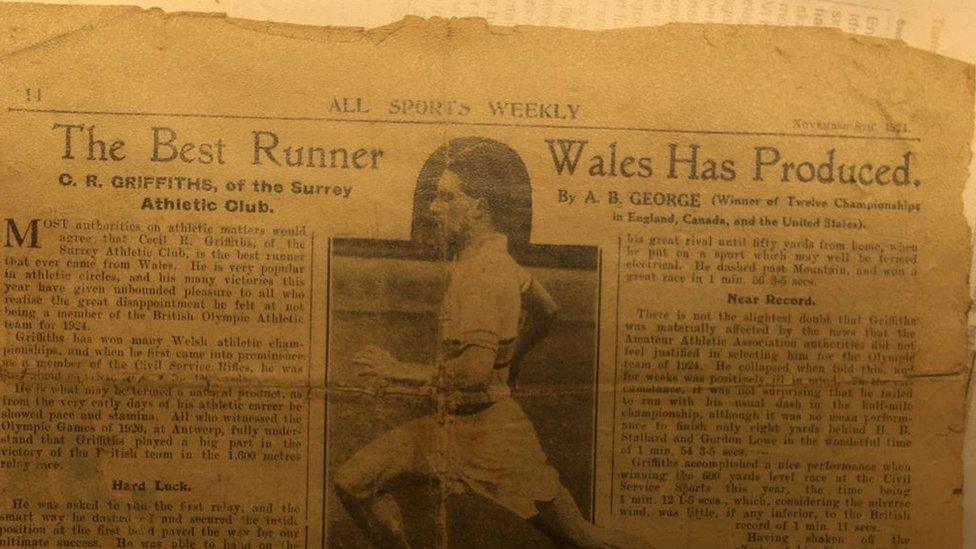

Griffiths was just 20 when he triumphed in the 4x400m relay at the 1920 Antwerp Games and one headline screamed he was 'The Best Runner Wales has Produced'.

But he was "robbed" of a shot at competing at the 1924 "Chariots of Fire" Olympics after a lifetime ban.

Now his granddaughter is raising money to get him the headstone "he deserves".

Griffiths, from Neath in south Wales, was just 20 when the former Territorial Army volunteer travelled to Belgium for his first - and what would become his only - Olympic Games in 1920.

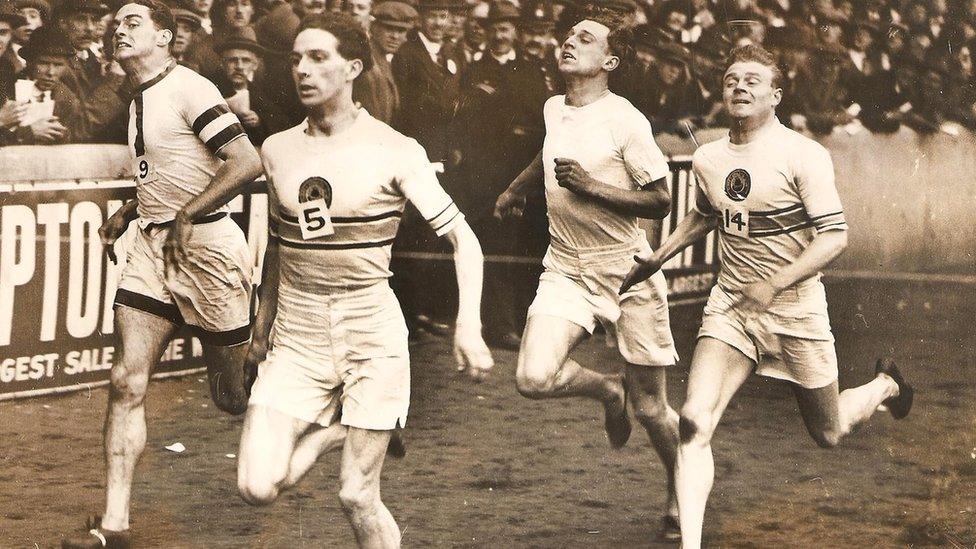

Illness forced the Surrey Athletics Club member out of the individual 400m event, but he starred in the relay and helped Britain win their first of just two 4x400m relay Olympic titles.

Griffiths built up an impressive lead in the first leg and his biographer John Hanna saying: "I have a newspaper article with the headline in The Times that reads 'The Best Runner Wales has Produced'."

Griffiths followed up his Olympic success with British half-mile titles in 1923 and 1925 and remained in the top three for nine years - but he would never compete for Great Britain at the Olympics again.

Olympic gold medal win a "marvellous achievement" for Cecil Griffiths

In 1923, the Amateur Athletic Association imposed a lifetime ban on him after discovering he accepted cash prizes - totalling £3 - as a teenager, which contravened their rules.

His biographer, also Griffiths' grandson-in-law, believes this "robbed" him of the chance of adding to his Olympic tally in the 1924 Paris Olympics which was immortalised in the film Chariots of Fire.

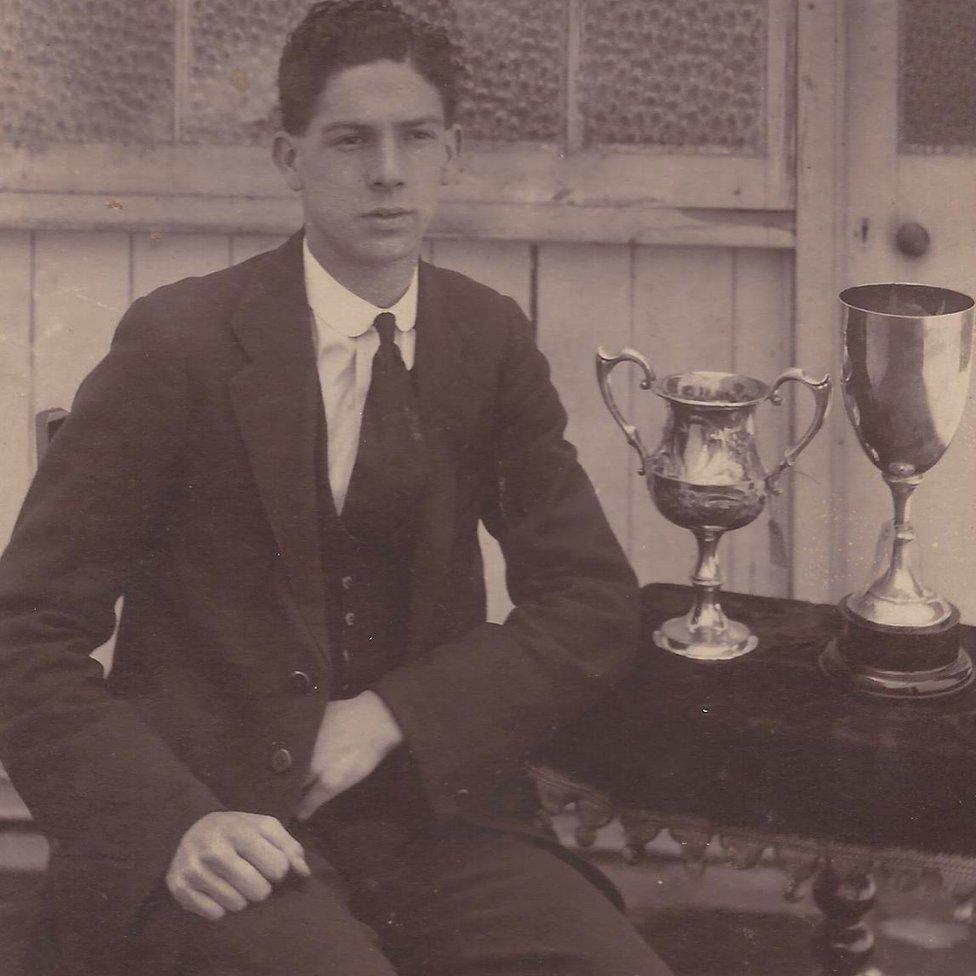

In 1931, facing financial hardship in the Great Depression, Griffiths sold all his medals and trophies apart from his Olympic gold.

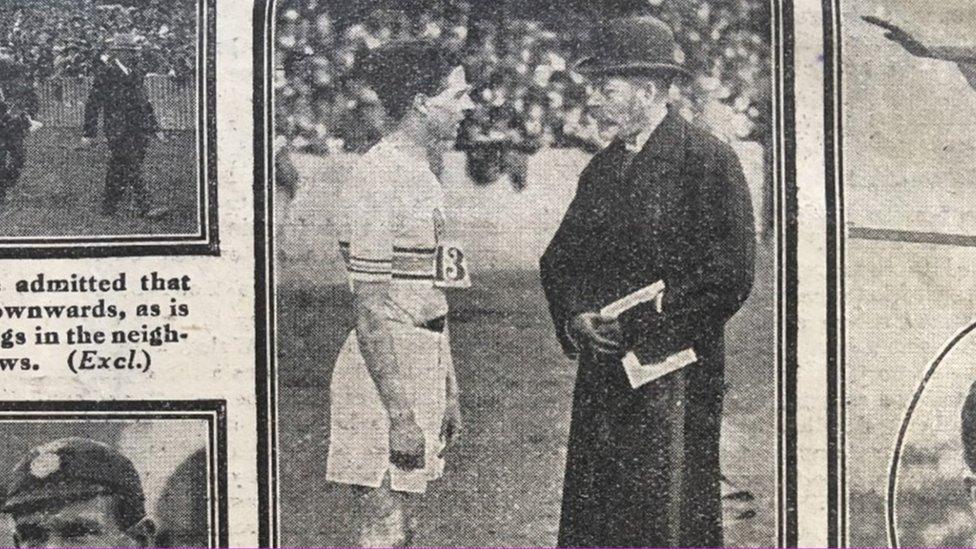

An old newspaper clipping shows Griffiths talking to the King after a race

Cecil Griffiths went on to become the British champion in the half-mile distance in 1923 and 1925

When he died aged 45 in 1945 in London, fianncial hardship meant his family were unable to afford a headstone for the former Olympic champion's grave at St. Lawrence's Church in Edgware.

Now his granddaughter Vanessa Hanna, who has terminal cancer, is determined to place a headstone at the unmarked grave of the Olympic gold medallist before she dies.

The 66-year-old, who is in the late stages of rhabdomyosarcoma, external, said her grandfather never recovered from the ban.

His family still has Cecil Griffith's Olympic gold medal from 1920

"I feel it was cruel when he was banned from the Olympics, he went into a deep depression afterwards," she said.

"He was robbed because he could have achieved so much more and I feel that now about myself being robbed of my life, because of cancer it has robbed me of a normal life with my husband and grandchildren."

Only one Welsh athlete has won Olympics track and field gold since he and Jack Ainsworth-Davis struck gold as part of the 4x400m relay team with Griffiths in Antwerp in 1920 - with just four Welsh Olympic track and field golds in history.

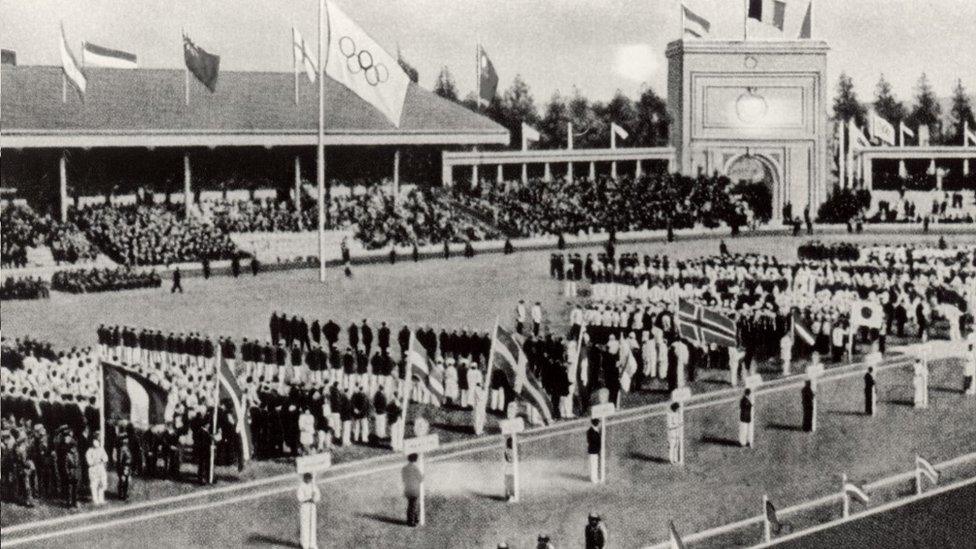

The Antwerp Olympics were the first to take place after the First World War

Last year, on the 100th anniversary of her grandfather's Olympic win, Mrs Hanna decided to take action.

"I feel very strongly he should definitely be remembered," she said.

"It means a great deal to me I've always felt so proud of him from a very early age."

Mrs Hanna said she had fond memories of taking his gold medal into school when she was aged six during the 1964 Tokyo Olympics- and believes a headstone is important for future generations:

"He's always been in my heart," she said.

"We want to recognise that he existed and give him a grand memorial forever more so our grandchildren can go there and pay their respects in a civilised way.

Vanessa Hanna and her husband John believe Cecil Griffiths should get more recognition

"I too realise now it's important for something like that to be at his grave so the family can visit and say hello when you've died and pay their respect."

Mr Hanna said he had regularly been beating the so-called 'Chariots of Fire' athletes from Oxford and Cambridge and the ban was a way for British athletics bosses to prevent the working class Welshman from competing.

"It was an era when sport was governed by the upper classes and this was a way for the AAA to get Cecil out of their hair," he said.

"He won £1 prize money when he was just 17 running in a charity event for the home guard in his hometown in Neath.

"A month later he took part in a race in Swansea and that was logged - he won £2 in that race which for his family would have been incredibly important."

'Criminal'

Mr Hanna, 66, said Griffiths' father died when he was eight-years-old so in a time with no social security and the prize money would have been critical for his mother and two siblings.

"Six years later, the powers that be found this information out when he started to beat their Oxford and Cambridge athletes and they used this against him and banned him at the end of 1923."

The family have kept news cuttings about their Olympian relative

He believes the ban stopped Griffiths from becoming a household name.

"He was described in a national paper as the best runner Wales has ever produced and I think that can still be argued today," he said.

"Only a few weeks before the 1924 Olympics, Cecil beat Douglas Lowe in the half mile race... he beat Lowe comfortably but with Cecil banned, Lowe went on to win gold at the Paris Olympics in the half mile.

"He could have run in the relay too so I believe he could have won a further two medals if he'd been allowed to compete and that would have put Cecil Griffiths right at the top of the league of British athlete's medal tally in track and field."

- Published23 August 2020

- Published23 August 2020