A&E queues mean Wales' ambulances 'can't take 999 calls'

- Published

'Relentless' demand on ambulance staff

As lockdown restrictions have eased ambulance staff are having the busiest summer of their lives.

But the pressure on hospitals to find free beds can mean long waits outside for the paramedic crews until their patients can be admitted.

Some say they are "broken" after spending so much time queuing outside A&Es - unable to respond to new calls.

BBC Wales' health correspondent Owain Clarke has been given special access to crews, and 999 call managers.

'Demoralising'

Osian Roberts said he spends most of his time queuing outside A&E

Paramedic Osian Roberts has spent most of his 12-hour shift in the back of his ambulance.

He is outside A&E at Glan Clwyd Hospital, in Bodelwyddan, Denbighshire.

He knows every inch of tarmac in the hospital's ambulance bay, because that is where he spends most of his time.

"We know there are people in the community that are screaming out for an ambulance, but as you can see, a lot of ambulances are waiting here," he said.

"It never ever used to be like this. We used to bring poorly patients in, and we were out on the road again in 15 minutes.

"We could do 10 jobs a shift, today we've done two. It's so demoralising."

Osian first arrived at the hospital at 09:30 BST, two hours after clocking on in Llandudno, to bring in a woman in her 90s, who had fallen at a nursing home and hurt her elbow.

The patient, who has dementia, was given blood tests and a heart check, but must stay with Osian in the ambulance until a bed becomes available.

It is almost three hours until that happens.

"It is frustrating," Osian said. "The patient is becoming a bit irritable and uncomfortable, but it's literally one out, one in, in the department."

By mid-afternoon Osian arrives at the hospital for a second time.

The situation is worse - there are eight ambulances queuing.

Osian is with a man in his 70s who has fallen at home and may have had a mini-stroke.

He knows if a patient arrives more urgently in need of help, his will be pushed back.

Osian and other paramedics must wait with patients until a spot in A&E becomes available

The longer he waits the less able he is to respond to calls.

"You feel you've let your community down," said Osian.

"Although we've done the best we can for the patient in our care, we know there are people out there waiting for ambulances and we can't get to them.

"And when we do get to them they're angry and cross, asking 'Where have you been?'"

The patient is transferred to A&E at 18:50, just before the end of Osian's shift.

The crew has responded to three calls since starting at 07:30, out of 440 across north Wales that day.

Matching piling numbers of calls with tied-up ambulances is putting control centre staff under pressure.

Particularly as they say the service has been dealing with more 999 calls than ever this summer.

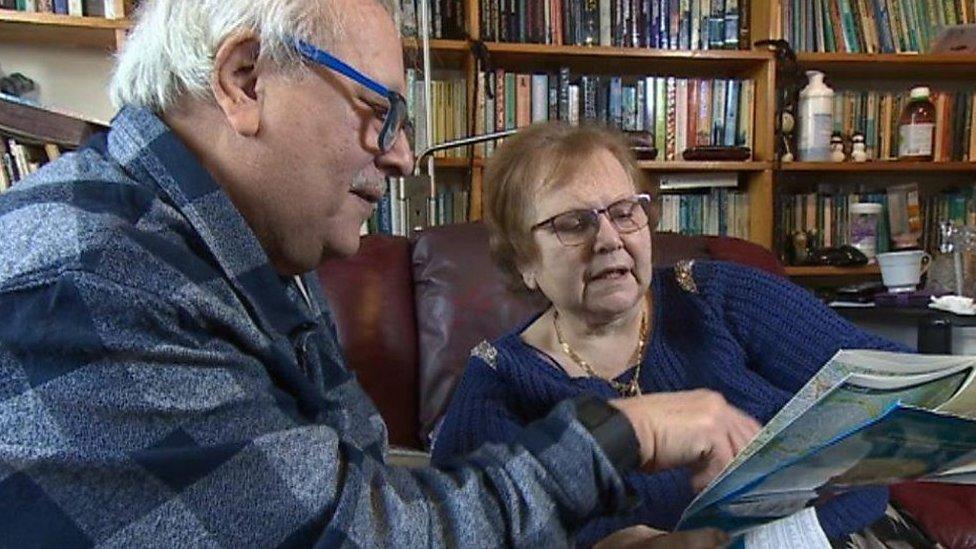

Ceri Roberts said this year was the busiest she had ever seen

Duty control manager Ceri Roberts has been in the service for 20 years.

"This year I think it's the busiest I've seen," she said.

"August is always a busy month but this time there seems to be no respite at all. We've got over 24 calls waiting for a response at the moment and the longest amber call has been waiting five-and-a-half hours."

The waits, Ceri said, can be longer.

"It's quite heart-breaking at times," she said.

"You can go home from a shift tonight and come back in tomorrow and see the same patient waiting in the stack, not having had an ambulance at all.

"You want to empathise and think, 'gosh, what if that was my parent or my family member?'"

The pressure on the north Wales service, she said, was caused by several factors.

They include the relatively elderly population in the area, a backlog in demand - as some have been reluctant to get symptoms checked during the pandemic, people more likely to be out as Covid restrictions have eased and, with fewer people travelling abroad, north Wales being busier than ever.

Dozens of calls can be waiting for responses at any one time

Senior paramedic Hefin Jones works on the control centre's clinical desk and gives advice over the phone.

"I've been in the service 30 years and I've never seen it as busy as this," he said.

"It's people coming out of lockdown, people not going abroad as we live in a touristy area. The number of people on Anglesey, say, is three times more than the usual population."

This is an "enormous worry," he added.

"The worst part, which we deal with a lot on the clinical desk, is people who've been waiting long, long hours for an ambulance response, but you don't have an ambulance to send.

"As clinicians we try to support them [on the phone] as best as we can."

Hefin said the post-lockdown workload had trebled with extreme pressures now routine.

He and Ceri urged the public to help ease the strain.

Senior paramedic Hefin Jones said post-lockdown the workload had trebled

"We've had all types of calls, from sunburn, fish-hooks in feet, cramp in legs, through to much more serious calls," Ceri said.

"I'd like people to think before they dial 999. It's not just a go-to number.

"We've got the 111 symptom checker online and that's a good place to start."

She said the difference would be "immense" if people thought more before dialling 999.

"It could mean that the patient who was waiting five hours today could have had a response in maybe 10 to 20 minutes," Ceri said.

Elsewhere, it is a worrying time for those working on the front line.

Emergency medical technician, Joanne Martin, is often on shifts relieving crews outside hospitals so they can take breaks.

"I've been coming into the hospitals during the crews' meal-break windows to allow them to have 30 minutes away from their vehicles," she said.

She had no answers to resolve the situation and feared the future held "bleakness".

Welsh Ambulance boss, Jason Killens, said the service was in "uncharted territory"

She said: "A lot of my colleagues have applied for other jobs or have left the ambulance service in the past six to 12 months and that's a great loss because they're good, qualified and experienced people.

"A lot of us feel pretty broken. It's not a positive future at the minute and a lot of people are weighing up their options."

Osian Roberts said the current pressures are leaving staff demotivated and demoralised.

Monitoring patients outside hospitals for hours was not the job he trained for 32 years ago.

He said: "Even though the job itself gives you great satisfaction, helping somebody and making somebody better, being here for hours on end with someone who is needy, and someone who is poorly does get you down.

"Pre-hospital care for me was about helping people out in the community, and bringing them to hospital, not being part of the hospital on the yard.

"I think [the system] needs drastic reforms."

Emergency medical technician, Joanne Martin, feared the future held "bleakness"

Welsh Ambulance Service chief executive, Jason Killens, apologised to patients who had endured long waits, saying the service across Wales was in "uncharted territory".

He insisted the service was working hard to deal with the situation and had recruited "over a couple of hundred" new staff in the past 18 months.

"We're recruiting and training more through the rest of this year, which will be (paramedics) on the streets as we approach winter," he said.

The Welsh government said getting patients from ambulances and into A&E remained a "significant challenge" and recently announced £25m to improve the outcome of emergency calls.

A spokesman said: "A range of local and system-wide factors contribute to these delays, including reduced physical capacity within emergency departments, increased levels of demand, and pressures elsewhere in the system."

Betsi Cadwaladr health board chief executive, Jo Whitehead, said it was working with councils to support patients who were fit to go home, but needed more help before they could be discharged safely.

She said: "This will help to improve the flow in our hospitals and discharge rates, which will support our ability to transfer patients from ambulances more quickly."

- Published20 July 2021

- Published22 July 2021

- Published28 July 2021