Drugs: How a county lines gang moved into Newtown

- Published

"It changed the way we lived, it got quite frightening"

A chainsaw slices through the front door of a terraced home.

It's a quiet cul-de-sac, on a new-ish estate, in a small, rural town in mid Wales.

Three doors away, for a brief moment Joy Jones tenses up. What fresh grief can the residents of this property be bringing to her street?

What she sees sends her running upstairs in delight. From the bedroom window she can see a street full of police, and her phone starts pinging with messages from neighbours.

"Everyone was shouting at each other and celebrating, the relief was unbelievable."

The police were finally arresting the drugs gang that had blighted their lives for nearly a year.

'It changed the way we lived'

Ms Jones has lived on the estate for over 20 years, raised her children there and sat on the county council.

But she could not stop the damage the gang inflicted on her neighbourhood.

"It changed the way we lived, it got quite frightening," she said.

People would turn up at the house day and night - buying, seeking or moving drugs.

Couriers - some just teenagers - would use one of a number of pedal bikes left on the front lawn to play their part in the sale and distribution of heroin and cocaine within the town.

"It was just horrible, it was like living in some kind of horror movie. It got so bad we would stay away from our home because we just couldn't bear to be here," she said.

And then there was the whistling.

"It was something they did when they were letting each other know something was going on, it seemed to be some kind of code," explained Ms Jones.

It was a stark contrast to the quiet, friendly neighbourhood she knew before.

The estate is a mix of privately owned homes and housing association properties.

When Anthony Butterworth first moved in things were fine, said Ms Jones, but when someone else moved in with him, it became a lot busier.

She estimates that in a 24-hour period, 50 people or more would visit the house.

"We'd see youngsters turning up, they'd knock the door, pick up a bike from the front lawn and disappear.

"We realised quite early on it was drugs being dealt there, but not the severity and the quantities."

'Drugs rife in communities'

Joy Jones said the "relief was incredible" when arrests were made

The house was being used by a Liverpool drugs gang as their safe house, where heroin and crack cocaine would be stored before being distributed in the town.

Just over an hour from Wrexham, less than two to Birmingham, with a population of about 12,000, it faced the same drugs problems as bigger towns and cities.

"It is rife within our communities," said Det Insp Gareth Grant.

At the time of the arrests he was head of Dyfed-Powys Police's serious and organised crime team - the unit charged with investigating the drugs that were infiltrating rural Powys.

"For the size of these towns, it was a major problem."

What did the operation look like?

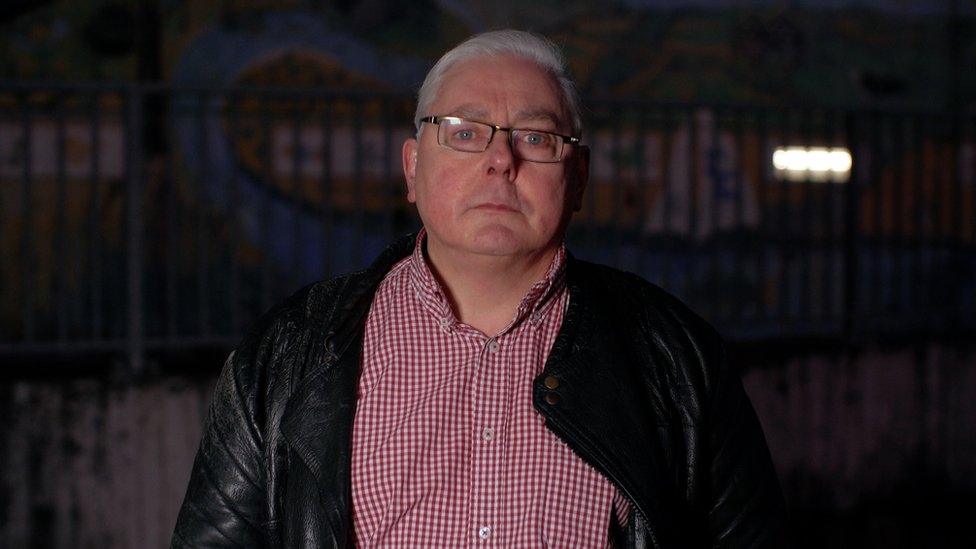

Det Insp Gareth Grant was head of Dyfed-Powys Police's serious and organised crime team during the operation

It's not a new phenomenon.

Just like a legal business, drugs gangs expand their operation, and seek out the profits to be made in smaller towns and communities.

But today you're more likely to hear it described as county lines.

And unlike the legal retail sector, violence will be used to drive out local dealers, while children or vulnerable adults will be threatened and coerced into transporting drugs and collecting payment.

So the risks are kept at arm's length from the gang and dealers make the sale remotely, using dedicated mobile phones.

"You had one individual working along the county lines model, embedded in that house with a vulnerable individual who lived there previously," explains Det Insp Grant.

"They would then send out messages and then the drugs would be taken from there for onward supply to individuals around the town."

Eighteen members of the gang were convicted

At the trial, Butterworth's barrister said the 52-year-old's involvement in the conspiracy to supply the Class A drugs had been relatively short-lived.

The gang only moved into his house when the electricity was cut off at the previous house they had been using.

Prior to that he had convictions for cannabis possession. The judge in the case acknowledged Butterworth had his own vulnerabilities, but he did not feel the gang had coerced him into working for them.

During the trial, the court heard over the space of 12 months, police received 46 calls about activity in and around Butterworth's house - which did not go unnoticed.

On the ground, officers targeted drug movement and sales with stop checks and searches but work was also done to get the community on board and increase calls to 999, as well as protecting others at risk of having their homes taken over by dealers.

Meanwhile, 80 miles away at Dyfed-Powys Police headquarters, the serious and organised crime team had been tasked with investigating the bigger issue of heroin and crack cocaine being shipped into two mid Wales towns.

Det Insp Grant had a core team of eight full-time detectives. He said they were arresting people throughout the duration of an 18-month investigation but they knew expectations were low.

"Right at the start I'm not sure the communities were assured we were going to have the impact we knew we could have," he said.

He was all too aware of the impact the drugs were having.

"It ruins the lives of the individuals taking the drugs, has a massive impact on their families, but ultimately it has a massive impact on the communities because of the associated crime trends we tend to see with this type of drug use.

"You'll see a massive rise in antisocial behaviour, associated thefts, violence, robberies etc they can all play a part in drug use."

He would not reveal the covert techniques used as part of the operation, but by the time they reached the arrest phase, 40 to 50 officers were involved.

"Over a million pounds worth of drugs were seized, we've now convicted 20 individuals of drug dealing offences, and they've been jailed for a total of 150 years.

"We were able to go quite a way up the chain in this investigation."

It is something the judge in the case acknowledged - praising the force for not being content targeting only the user or street dealer but "the source".

The leaders of the conspiracy, Jack Ross, Karl O'Hara, Michael Williams, Ryan Langshaw and Daniel Putterill, all from Liverpool, were sentenced to a total of 47 years for the supply of Class A drugs into Newtown and Llandrindod Wells.

Anthony Butterworth received five years for conspiracy to supply drugs and died in prison last year.

What difference did the arrests make?

The property that was used by the gang is still boarded up

It depends who you ask.

For Ms Jones and her neighbours - the difference was obvious and "it's wonderful".

The force have said since 2019 no county line has been identified in the region.

Det Insp Grant said: "It is one of our biggest challenges that when we conclude one investigation the big thing for us is trying to prevent something getting as much of a problem again - and it is very difficult.

"What we will have then is people trying to establish themselves as the new drug dealers within those towns. It's up to us - along with a multi agency plan - to have something in place where we can try and prevent these problems escalating."

In practical terms, that means making arrests the minute new dealers emerge - so other gangs cannot fill the void created.

"But it'll certainly make a big difference for a town this size for quite a considerable amount of time," he said.

Barry Eveleigh says more money needs to go into treating drug addiction

Barry Eveleigh, from drug and alcohol charity Kaleidoscope, said the arrests had not made much difference as "markets are replaced pretty quickly".

He said: "If anything you find the purity goes down, prices go up and potentially people have to commit more crime in order to fund the same habit.

"You want a substitute, which is what treatment services can offer. But by and large that doesn't happen."

"On average we might see someone twice a month - how can you change somebody that's been addicted to heroin for 10 years just by seeing them for an hour, twice a month? It's very, very difficult."

He said the violence associated with drugs was also an issue, but he said: "I don't want to start panicking people that Newtown is a place that's rife with drugs, knives and violence.

"It's just a small undercurrent that generally doesn't spill out into the wider community. But when it does it can be quite serious."

MOTHERS, MISSILES AND THE AMERICAN PRESIDENT: The story of Greenham told like never before

CITY OF HORSES: The people and traditions behind Swansea's urban horse community

- Published1 September 2021

- Published20 December 2019

- Published14 January 2020