Cardiac arrest: Thousands of defibrillators unknown to 999 service

- Published

Could cooling make survival more likely after cardiac arrest?

Tens of thousands of defibrillators across the UK risk being unusable because 999 call handlers do not know about them.

When someone has a , external, ambulance staff can only direct bystanders to the nearest defibrillator if it is on a central register.

"That could be the difference between life and death," said Adam Fletcher, head of British Heart Foundation Cymru.

A campaign to register defibrillators on The Circuit, external has now been launched.

Sales of defibrillators rose after footballer Christian Eriksen's cardiac arrest during Denmark's opening game of the European Championships in the summer.

The device - which gives a high-energy electric shock to the heart - was used as part of the emergency action that saved Eriksen's life after he collapsed on the pitch.

One was also used to help save a football fan who collapsed in the stands during Sunday's Premier League match between Newcastle United against Tottenham Hotspur at St James' Park.

Survival rates are low in the more than 30,000 out-of-hospital cardiac arrests each year in the UK, according to the British Heart Foundation (BHF) - with fewer than one in 10 people surviving.

How to use a defibrillator and save a life

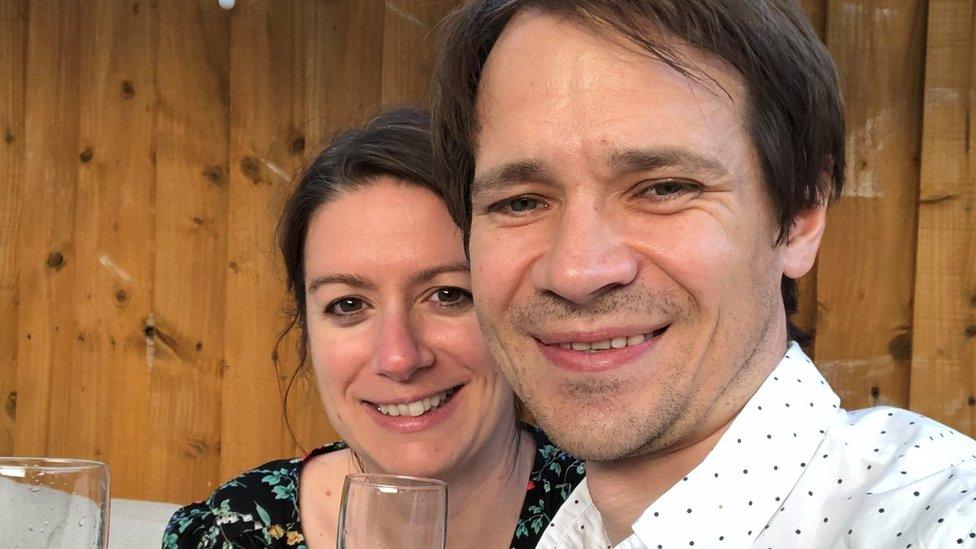

Andrew Barnett was 46 when he had a cardiac arrest in 2018 while playing in a parents v children football match.

When he collapsed, leisure centre staff ran to his aid, with a defibrillator, including Sheila Mott, who opened the defibrillator box while her colleague started mouth to mouth on Andrew.

"The pads went on him and Ben [her colleague] started to do compressions - then the machine said to halt and it was analysing his body, so we stopped," said Sheila.

Andrew Barnett feels lucky he had a cardiac arrest where a defibrillator was available

Sheila explained the machine then signalled that a "shock" was required.

"I just pushed the shock button, then it analysed the body again and said to start CPR, which Ben did and we didn't have to shock him again," she said.

Andrew, who is involved in the BHF's campaign, added: "I was really lucky - I was in the right place at the right time, with trained staff who knew where the defibrillator was and it was working.

"It's a bit of a lottery at the moment. You feel that you were the lucky one, and then you feel really sorry when other people aren't in that position."

Sheila has been doing first aid training for more than 30 years, and now trains others to use defibrillators, both with Girlguiding and the Royal Life Saving Society.

Sheila Mott says the machine expains what needs to be done to help save a person's life

"I feel quite proud of myself. That's the first time I've used it for life - to save somebody," she said. "But I've always practised every month with them.

"We do CPR training with Brownies and the older children learn to use the defib. I think it's very, very important it gets across to all age groups - if they cannot manage the compressions on an adult, they might be able to tell somebody how to do it."

The charity, the Resuscitation Council UK, St John Ambulance and Association of Ambulance Chief Executives, said the UK's low survival rate was partly because defibrillators are used in fewer than one in 10 out-of-hospital cardiac arrests.

BHF said early CPR and defibrillation could double the chances of surviving and it was often down to 999 call handlers being aware that a defibrillator was nearby.

"If we don't know a defibrillator is there, we can't send somebody to get it, to potentially save somebody's life," said Carl Powell, the clinical support lead for cardiac care with the Welsh Ambulance Service.

Shakin' Stevens said he nearly died after a cardiac arrest and now campaigns for more CPR to be taught

While the 14 UK ambulance services previously had their own databases, The Circuit will eventually replace these with a new national database.

But of the 5,500 in Wales that are registered, there is another challenge - more than half risk being redundant without a "local guardian" who looks after the defib and makes sure it works.

"We can't be 100% certain those defibrillators are rescue ready at any one time," Mr Powell said.

"If we deploy one of those defibrillators that doesn't have a guardian, we take it off the system until a guardian checks it."

He explained ambulance staff would make those physical checks when possible, but it was a resource-intensive task for a service already under pressure.

Medical emergency

"It's a question of communities who have worked so hard to get public-access defibrillators, to actually look after them - to make sure the batteries are still functioning or the pads are within date - so that if they're needed in a medical emergency, they're ready to go," he said.

"Unfortunately we hear these stories, where it's turned out there was a defib maybe 100 yards round the corner," said Mr Fletcher.

"But because it wasn't registered, the call handler at the ambulance service couldn't direct that bystander to get it. And that's what we want to end.

"The current situation is tens of thousands of defibrillators are not currently registered, and the ambulance service don't know where they are which is obviously a big problem."

The Welsh government recently announced £500,000 additional funding for the Welsh Ambulance Service and Save a Life Cymru to buy nearly 500 defibrillators - a condition of which is that they must be registered on The Circuit, with a local guardian.

HEART AND SOUL : Ray Lopes is young, gifted and black; tonight's the night

TIP NUMBER 7: The families of Aberfan fight for justice

Related topics

- Attribution

- Published18 October 2021

- Published1 October 2021

- Published15 September 2021

- Published23 August 2021

- Published22 August 2021

- Published18 July 2021

- Published18 June 2021

- Published16 June 2021

- Published14 June 2021

- Published16 October 2017