Llanelli school strike: The schoolboys who defied the cane

- Published

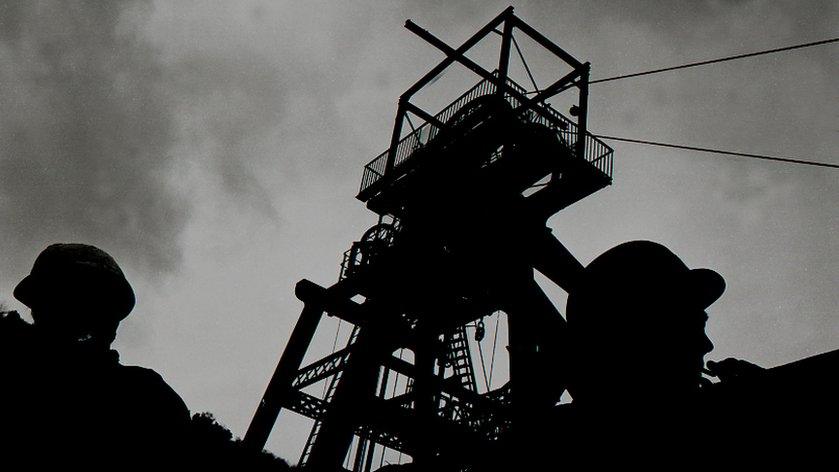

A strike at Llanelli railway station in August 1911

You may have thought Greta Thunberg invented the concept of school pupil strikes.

But around a century before the Swedish teenage activist called the world's children out on to the streets to campaign over climate change, schoolboys in Llanelli were already at it.

In 1911, about 30 pupils from Bigyn School walked out in protest at the "unjustified" caning of a fellow boy.

Although the Llanelli strike was quelled within a day, it spawned similar protests in 62 towns and cities across Britain and Ireland.

Historian Russell Grigg recounted the disturbance in a 2003 article for The Local Historian journal, external.

"Between 1910 and 1914 most of Wales, and indeed the whole of Britain, was caught up in a period of industrial strife known as the Great Unrest," Mr Grigg told BBC Wales.

"Here it included the Tonypandy coal strike, the anti-Semitic Tredegar riot, and in particular in Llanelli, the railway strike."

On 5 September 1911, the boys marched and sang their way through the streets of Llanelli, waving placards and calling on the pupils of other schools to join them - New Dock, Lakefield and Old Road schools came out in solidarity.

En route, they stopped at Park Street Chapel and held animated discussions on what to do next.

'Someone must die for the cause'

Historian Russell Grigg says it would have taken great courage for children to go on strike in 1911

While some of the children were out for a laugh, a politically aware hardcore was more determined to pursue their cause.

A flavour of the mood survives in the melodramatic words of one pupil who went on to lead the strike in Newport: "Comrades, my bleeding country calls me, the time has come. Someone must die for the cause."

Having made their point, the Bigyn boys returned to school up the hill.

Yet Mr Grigg said it should not be underestimated how much courage it must have taken those 30 pupils to walk out.

"Corporal punishment worked, wrongly, on two levels: Firstly, the physical pain of being hit, but more significantly the fear of receiving a beating," he explained.

"For those 30 boys to march out of their class, either the problems they were facing were so severe that they'd overwhelmed the consequences of a thrashing, or else the prospect of the social isolation they'd have received from their classmates was more terrifying than any caning the teachers could impose."

In Wales at least, the strike was written off as little more than children acting out the industrial disputes of their parents during the Llanelli railway strike and ensuing riots.

"From Cork to the East End," Mr Grigg says the strikes were sparked by a "genuine sense of injustice"

Indeed, one boy told a Daily Mirror reporter: "My dad is striking for his rights, why shouldn't I?"

However, Mr Grigg said he believed there was evidence to suggest the pupil strikes were a protest in their own right.

"You only have to look at the range of complaints the children had, and the number of cities it spread to, to realise that this was far more than just copycat," he said.

"From Cork to the East End - with issues ranging from corporal punishment, the length of the school day, holidays and the price of books - this was a genuine sense of injustice."

Classroom tensions

Spread through word of mouth and newspaper reports, thousands of pupils protested in a month of disturbances.

In Dublin, children pelted teachers and parents with rotten cabbages, while in London youths with sharpened sticks pillaged the streets.

Mr Grigg said the strikes highlighted the challenges and tensions in the school system.

"Education was far more fragmented between local authorities than it is today, so it's impossible to give one answer to what effect the strikes had," said Mr Grigg.

"From the late Victorian period, more enlightened educationalists such as the chief inspector of elementary schools Edmond Holmes had been advocating major reforms including a move away from teaching to tests, a more engaging curriculum and less discipline through fear.

"They hoped the 20th Century would be the century of the child with more child-centred teaching and a greater recognition of children's rights and voices.

"But corporal punishment remained a source of tension between teachers and pupils. While the local authorities made it clear that girls and infants were not to be hit, and reminded schools that corporal punishment should only be used as a last resort, in practice, abuses continued."

Preparing schoolboys for war

It would be 75 years before corporal punishment was banned in state schools

The two sides would be drawn closer together by the need to provide troops to fight in World War One.

Mr Grigg explained: "One thing that worried the authorities was that the school system was turning out boys who were too physically unfit to fight, something that had been noticed when recruiting for the Boer War at the turn of the century.

"This is why there was a greater emphasis on physical training and military-style drill exercises in school. It was thought that this would instil much-needed self-discipline. Corporal punishment was part of this culture of character formation, seen by many teachers as a means of maintaining classroom order and not likely to do much harm in the long run."

While school strikes petered out, Mr Grigg said he believed they did raise themes which continue to occupy modern-day educationalists, such as listening to what pupils have to say, creating engaging lessons and working with parents.

Corporal punishment was eventually banned in state schools in 1986.

Scotland was the first of the UK nations to ban smacking in 2020, with Wales following suit next year.

THE LONG WALK HOME: 20,000 miles, 4 years, 1 man

FORENSIC COLLISION INVESTIGATORS: Step inside the cordon with The Crash Detectives

- Published19 June 2019

- Published22 April 2018

- Published18 May 2017

- Published7 October 2015

- Published20 November 2014

- Published13 March 2014

- Published19 January 2012