Island Farm prisoner of war camp volunteers battle to buy visitor centre

- Published

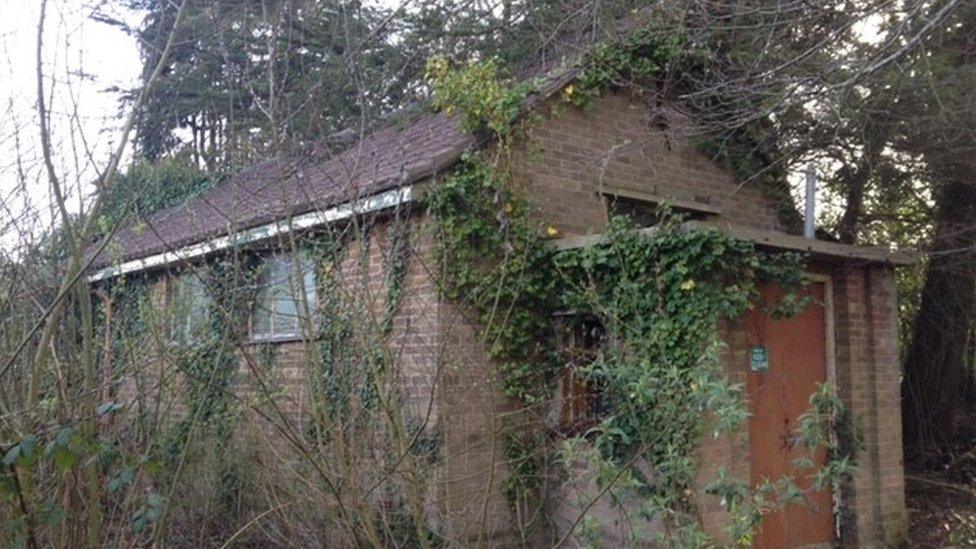

The visitor centre houses the museum about Hut 9 and Island Farm prisoner of war camp

Volunteers are trying to save a visitor centre on the site of the biggest escape attempt by German inmates on British soil during World War Two.

The group has spent nine years restoring Hut 9 on Island Farm prisoner of war camp in Bridgend.

On 10 March 1945, 70 German prisoners of war tunnelled their way out of the hut, which is now owned by the council.

Island Farm's privately-owned visitor centre is for sale and Hut 9 Preservation Group has first refusal.

Inside Hut 9 lies the entrance to the now sealed tunnel

The volunteers, who over the years have welcomed thousands of visitors to the centre, are trying to raise £40,000 and said a crowd-funding campaign was their only hope.

Brett Exton, chair of the group, said: "We've enjoyed a very healthy relationship with our landlord since we began in 2012 - he's allowed us to operate rent-free, and in return we've ensured the maintenance and security there."

"We've been offered a very fair price, but it's still an enormous amount to raise if we want to carry on with our open events, which are always fully booked, with 1,200 attending over a weekend."

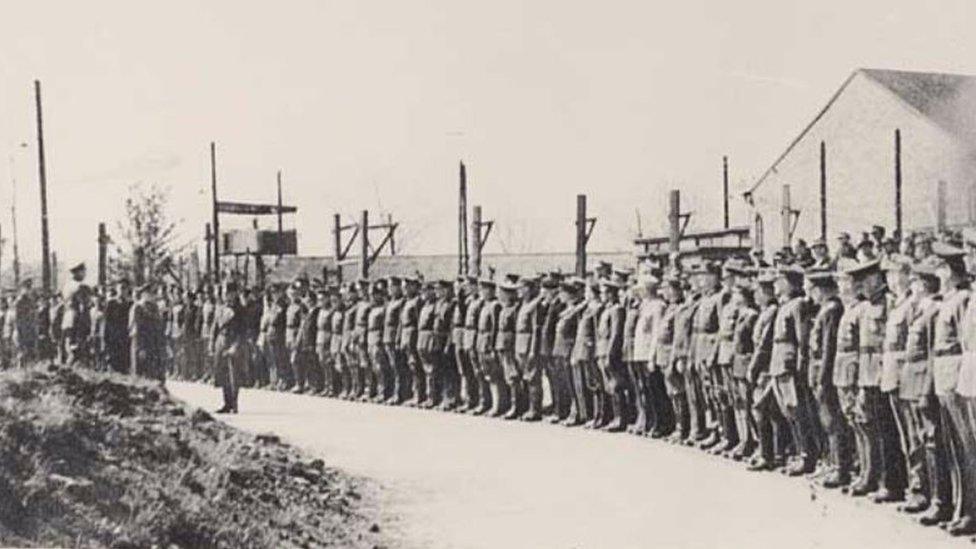

Hut 9: German prisoners of war tunnelled out from the hut in their escape bid

What is the history of Island Farm?

Island Farm started out life as accommodation for female munitions workers before it was requisitioned to provide barracks for United States soldiers ahead of the Normandy Landings in 1944.

It was then repurposed to hold thousands of captured German troops.

From the air: Island Farm in 1947

On 10 March 1945, 70 German soldiers tunnelled their way out of Hut 9 and under the perimeter wire.

They used slotted-together condensed milk cans to provide a ventilation shaft, lighting was wired to the camp's electricity supply, and tunnel props were cut from the camp's bunk beds.

Curry powder was sprinkled around the perimeter fence to confuse sniffer dogs.

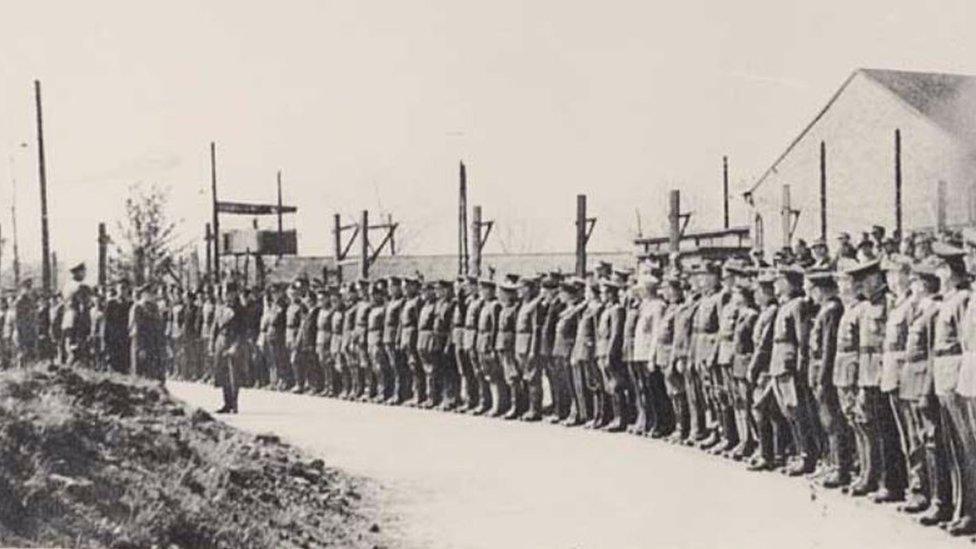

Officers at Island Farm salute Field Marshall Gerd von Rundstedt as he left to attend the Nuremberg war crime trials as a defence witness

Of the 70 prisoners of war, most were rounded up within a day or two but some made it as far as Swansea, Southampton and the outskirts of Birmingham.

"It seems incredible that all this work was able to take place undetected - it really was an entire camp effort," said Mr Exton.

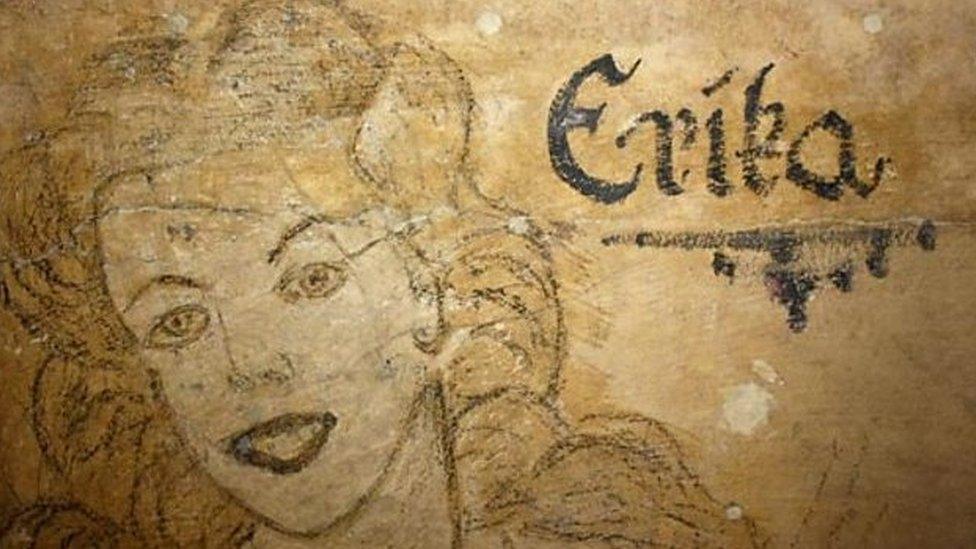

Graffiti drawn by prisoners can still be seen at the hut

"Although only a small proportion of the PoWs tried to escape, every single one of them would have been involved with providing distractions for the guards, including staging a play on the night of the break-out, and forming a raucous choir in the next door hut while the tunnelling was taking place."

Today, all that remains of the original camp is Hut 9 and the tunnel below.

When Mr Exton and his friends first unearthed it, it was neglected and vandalised.

Until now the volunteers have been allowed to use the centre free of charge

But the damage did reveal some secrets - a collapsed wall showed how escapees had rolled the clay soil they had excavated into balls and thrown them behind a false partition in the hut.

Following preservation work, the hut now looks as it would have in 1945.

The group has also had to contend with a colony of bats who share the hut, as well as the great crested newts and dormice that live nearby.

While the future of the hut itself is not under threat, Mr Exton said the visitor centre was essential: "If someone else were to purchase the site... the visitor centre would almost certainly have to be demolished.

"It houses our museum of all the artefacts we've been able to collect over two decades, and also provides a lecture theatre-style room where we give a talk before a visit to the hut."

He said the group's busiest weekends were around Armistice Day and the March anniversary of the escape, when "the weather is not often that good... and would probably put off visitors".

The Hut 9 Preservation Group has launched a crowd-funding campaign which has so far raised over £5,500.

Mr Exton said there was no deadline but "such an attractive site could sell as early as Christmas, so we really do need to crack on".

DEAR MRS CAMPBELL: A letter of celebration to Wales' first black headteacher

THE CASABLANCA: How a Cardiff nightclub changed our lives

Related topics

- Published6 June 2014

- Published4 January 2021

- Published6 June 2024

- Published7 March 2020