Aberfan disaster: Surviving schoolchildren's trauma 55 years on

- Published

In 1966, 116 children and 28 adults were killed when a coal waste tip came crashing onto a school and its surrounding homes

Fifty-five years may have passed since the Aberfan disaster but Jeff Edwards still cannot get the image of his dead classmate resting on his left shoulder out of his mind.

The then eight-year-old was one of 240 schoolchildren at Pantglas Junior School when a coal waste tip came crashing down a hillside, engulfing the school and surrounding homes.

On that day - Friday 21 October 1966 - 116 children and 28 adults died, decimating the close-knit and thriving Merthyr Tydfil community in the south Wales valleys.

Jeff said the physical injuries he suffered that day healed in time but decades on his psychological trauma would "never really be dealt with".

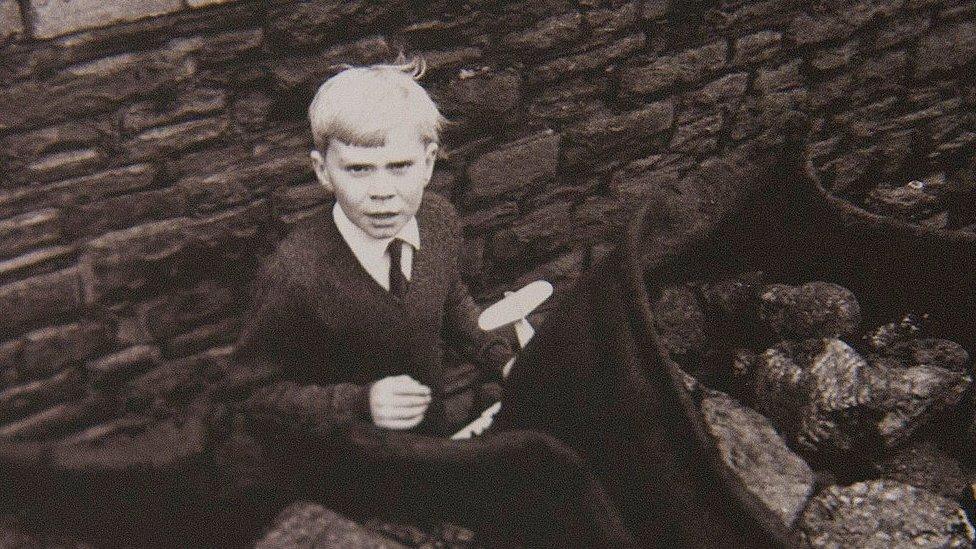

Jeff Edwards was only eight when he lost many of his friends

Little Jeff's day had begun like so many others, walking to school through his mining village which was prospering around Merthyr Vale Colliery.

He called in the tuck shop for his usual selection of sweets - pink shrimp, flying saucers, sherbet.

But at 09:14 that morning his life changed forever.

Jeff was the last surviving child to be rescued from Pantglas Primary School

"One minute you were a young lad looking forward to the half-term holidays, waiting for the lesson to start and the next minute I had death on my shoulder and had to grow up very, very quickly. My life had totally changed," he said.

He and his classmates Gaynor Madgwick and Gerald Kirwan, who were also eight at the time of the disaster, have been recalling the events of that day for BBC podcast Aberfan: Tip Number Seven.

Gaynor lost a brother and sister in the Aberfan disaster

'Black mass'

Gaynor was waiting for her teacher to begin a maths lesson when "within seconds this noise appeared completely from nowhere".

She said: "It was the most horrific noise, thunder - louder, louder and louder."

"It was like the noise of a jet airplane or something," added Gerald.

Gaynor said: "I remember turning my head seeing this black mass and trying to get up and run for the door.

"Then it was blackout. It literally froze people in their seats."

"I could see the big black mass hitting the windows," recalled Gerald.

"I think I was knocked out".

Jeff was trapped: "The next thing I remember is waking up with all this material that had come from the other side of the room on top of me.

"All this material was over me, and all these screams and shouts, but the lasting memory for me was the young girl's head on my shoulder...

"When I think of the disaster, that [image] was going to cause the problems for many years to come," he said.

'I just lay there'

"I never remember the slurry hitting me," said Gaynor.

"When I woke up I'd been catapulted to the back of the classroom - I just remember looking around desks, chairs, mud, slurry.

"I just lay there, I wasn't screaming, I was in shock."

Local men and the emergency services formed a line to pass freed children out of Pantglas Junior School

Amid the screaming and the chaos, Gaynor realised some of her classmates had not survived the impact: "There was another little boy who was sleeping, he didn't have any slurry over his face but as a child you immediately know that that child is dead.

"Even as a child you know what death is," she said.

Hours later Gaynor would learn that her brother Carl, seven, and sister Marylyn, 10, who had been in neighbouring classrooms had also lost their lives that day.

"I remember distinctly there was another child's arm that had gone through a crack in the wall from the other classroom and was just hanging," she said.

"I don't know why but for some reason I was just holding on, pinching this hand and wanted this hand to move.

"When I look back now, and when I heard my brother had died, I always hold onto the hope that with me holding onto that child's hand it could have been my brother's.

"I hold onto that, it gives me comfort."

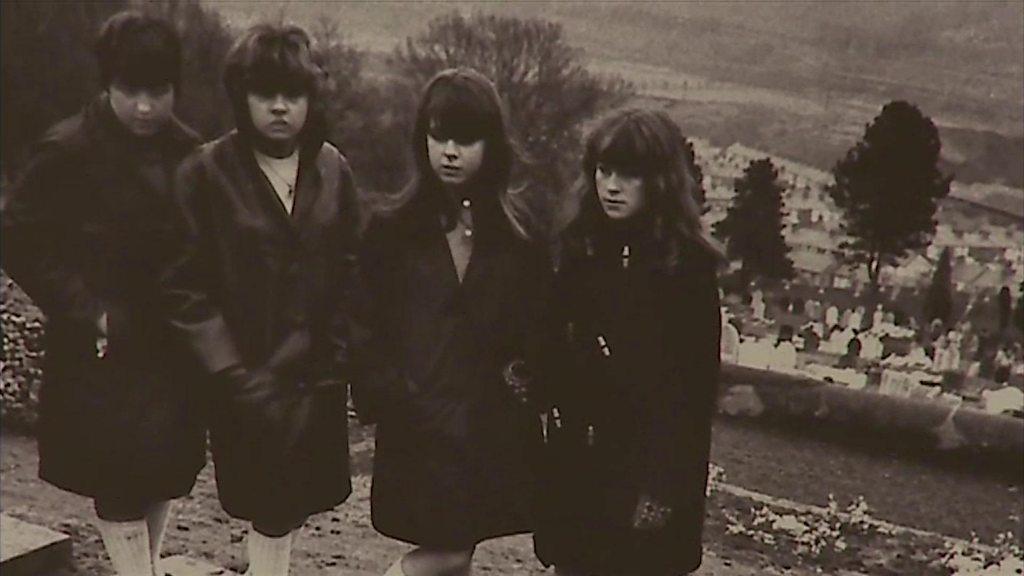

Gerald (pictured), Jeff and Gaynor all still live in Aberfan

'Earthquake'

When Gerald came round he was confused by the chaos around him: "I didn't know what had happened, I thought there'd been an earthquake or something.

"Everybody was screaming and crying," he said.

He saw one of his classmates, a young girl, had managed to get on top of the shattered school roof and was shouting that she was going to get help.

"Years and years later she said to me it'd played on her all her life that when she went out of that school, she run home and never told anybody where I was," he said.

"She said 'if anything had ever happened to you I don't know how I would have lived my life'.

"And I said 'If I could have got out love, I'd have done the same. I would have been gone'.

"You couldn't imagine as a little eight-year-old growing up thinking that... throwing that about in her head for all these years. What a thing to live with."

The trapped children could do little but to wait for help to arrive.

A mass funeral for 81 children and one adult was held a week after the tragedy

'Despair in his eyes'

"Where there were screams and shouts before, those screams and shouts got less and less as time went on," said Jeff.

"Effectively people were dying while we were just lying there in the disaster."

Eventually help did begin to arrive.

"The first face I remember seeing was my grandfather's," said Gaynor.

"That moment of despair in his eyes when he looked at me, I'll never ever forget that for the rest of my life - it was only then that I started to cry."

Gaynor had to wait while the rescue team dug out other children and removed debris before coming to her.

"I was handed to a chain of different people helping, through the window, then you were outside… my legs were just literally swinging because I'd broken my femur," she said.

She was carried through the commotion that had sprung up around the disaster site: "Sirens, ambulances, parents, chaos, everybody was running everywhere trying to find their children."

She was soon reunited with her mother: "For a very brief moment [she] didn't really care about me. She knew I was okay, she knew I was out, she knew I was alive.

"She wanted to go and find Carl and Marylyn."

'Really affected me'

As the first children were being pulled out of the rubble Prof Sir Mansel Aylward, then a 23-year-old medical student, was driving home to Merthyr Tydfil for a christening.

As he got to Dowlais Top he was pulled over by police who told him he could not go any further because there had been a disaster in Aberfan.

On realising his medical training they sent him to the school to assist the rescue effort.

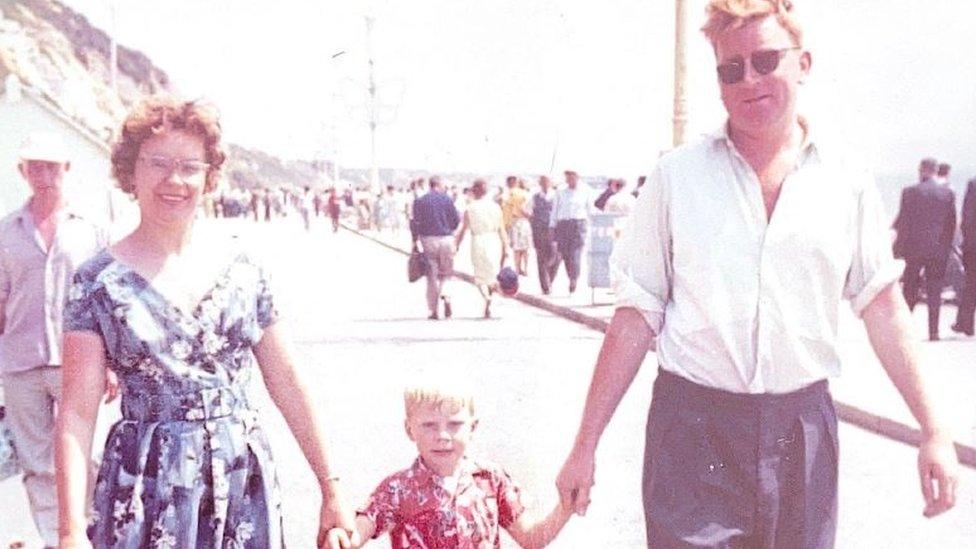

Jeff, pictured with his parents, says his psychological injuries from the tragedy have never been dealt with

"Up until recently I couldn't talk about this, what I saw will never leave my mind," he said.

"All the children were at their desks and they were covered in sludge, mud and had obviously died by suffocation.

"The teacher was dead as well, and he was standing in front of the children with his arms out, as if trying to protect them. That really, really affected me."

Gerald was eventually rescued and taken to a nearby house.

Two hours after the school was struck, a rescuer spotted Jeff's blond hair among the rubble and he was the last surviving child to be rescued.

With all the ambulances having already left the scene, he was taken to hospital in a greengrocers' van.

His younger sister Julie, then five, also attended the school.

He was later told she had been away from the school on a walk with her teacher and classmates when the spoil tip came crashing into the school, avoiding the disaster.

As the rescue effort continued and dead bodies were pulled from the rubble, Bethania chapel was turned into a makeshift mortuary.

Prince Charles met Gaynor and Gerald during a visit to Aberfan to mark the 50th anniversary of the disaster

Volunteers washed the slurry off the children, wrapped them in blankets, labelled them with a physical description and any items they were carrying and laid them out on pews.

Parents stoically formed a queue in the pouring rain outside.

'Never spoke about it'

Gaynor had been in hospital since being rescued that morning but her parents were yet to visit as they were searching for her brother and sister.

"It wasn't until the night time that my parents and my gran came in," she said.

"I asked if Carl and Marylyn were okay, and my father said to me 'Gaynor, they've gone to heaven'.

"That was the only time we spoke about it, never spoke about it after.

"No-one said to me about it, what had happened, how you were. It was basically a shower of love, nothing else.

"I was left to deal with that in silence and that silence continued for many years.

"I never, ever, ever got my answers."

Some of the 144 victims of the tragedy are buried at Bryntaf Cemetery in Aberfan

'Psychological injuries'

It was dealt with in much the same way in Gerald's family: "From the day it happened it was never mentioned again, kind of taboo," he said.

"I never spoke to my brothers or spoke to my mother and father about it, nothing. It was like a secret, our little secret."

Jeff and his sister Julie both survived the disaster

Fifty-five years may have passed but some wounds have yet to heal.

"As far as injuries were concerned, I sustained injuries to my head and my stomach," said Jeff.

"Those physical injuries would resolve themselves pretty quickly but it was those psychological injuries would never really be dealt with.

"You've got that for the rest of your life."

The podcast Aberfan: Tip Number Seven is available to download from BBC Sounds from 20 October.

A KILLING IN TIGER BAY: The full and shocking true story

Related topics

- Published19 October 2016

- Published13 September 2016

- Published10 April 2021