Social care crisis: Woman, 92, waited four months to be discharged

- Published

Mrs Hanson's family felt "lucky" to bring her home, eventually

Just a week after being admitted to hospital with an infection, 92-year-old Esme Hanson was well enough to go home.

But it would be four months before she could return to her family because of a lack of available care.

One care provider told BBC Wales staff shortages were so bad, it handed care packages back to the local council.

The Welsh government admitted the situation was "fragile", and it had committed £48m of extra funding to ease the social care crisis in Wales.

When Mrs Hanson became unwell in May, she was admitted to Morriston Hospital in Swansea. Her care arrangements, put in place due to her dementia, were cancelled.

However, it was not until September that a new package was finally re-instated, by which time her mental health had deteriorated, according her son Andrew.

He said his family were "lucky" to finally get her home.

"If you've got somebody over 70 that needs care, you don't know when they're going to come out of hospital," he added.

Esme Hanson spent four months in hospital waiting for home care to be arranged

It was only after the Older People's Commissioner for Wales advised the family to organise their own care, and ask the council to fund it, that Mrs Hanson's care arrangements were put in place and she was discharged.

He said his mother now received "wonderful" care at home three times a day.

Swansea council said it was extremely sorry for the delay and that every effort was made to find a package of care with a provider during the "unprecedented" times of the coronavirus pandemic.

But Mrs Hanson's experience is not unique. There were more than 1,000 patients in Welsh hospitals unable to return home due to a lack of care, according to Welsh government figures, external last month.

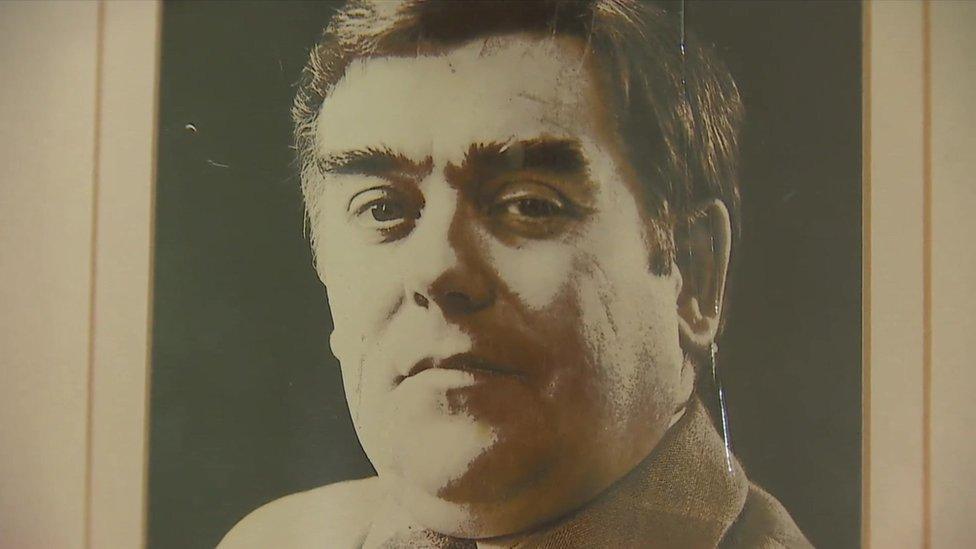

Care company director Keri Llewellyn said staffing levels were at their lowest for almost 20 years

Care Forum Wales has warned the care sector is facing its biggest staffing crisis "in living memory".

One home care company, All Care, said staffing levels were at their lowest since 2002 and recruitment has been "virtually zero" for months.

Director Keri Llewellyn said "a downward spiral" of staffing shortages meant companies were handing back care packages to councils.

She added care staff were exhausted from working through the pandemic, while low wages made recruitment and staff retention difficult.

"I do need something for my staff now. Some hope, maybe a retention bonus," said Ms Llewellyn.

The strain of working through the pandemic has told on carers such as Nicola Peta Hales and Jane Davies

Care manager Jane Davies has been helping with daily rounds due to staff shortages.

"You are very tired and you need to spend time with your own family, but you can't see those people go without care," she said.

Nicola Peta Hales, 54, said the stress of being a domiciliary care worker almost became too much.

"I did feel like quitting and I was very close to it not so long ago, but I decided to stay because I love the job."

The Association of Directors of Social Services (ADSS) Cymru has called on the UK and Welsh governments to provide more help.

Last month, the UK government announced a national insurance tax rise, some of which will be used to help fund the care system. On Wednesday, the chancellor is due to outline spending plans for the next three years.

The Welsh government admitted the situation was "fragile".

Deputy Minister of Health and Social Care Julie Morgan said implementing a living wage of £9.50 per hour for carers was a priority, along with improving working conditions.

"We have to get the system to a place where there are not long waits," she added.

- Published1 September 2021

- Published14 September 2021

- Published7 September 2021

- Published3 September 2021

- Published18 June 2021

- Published17 March 2021