Barry: Mystery behind donation of WWI victim's medals

- Published

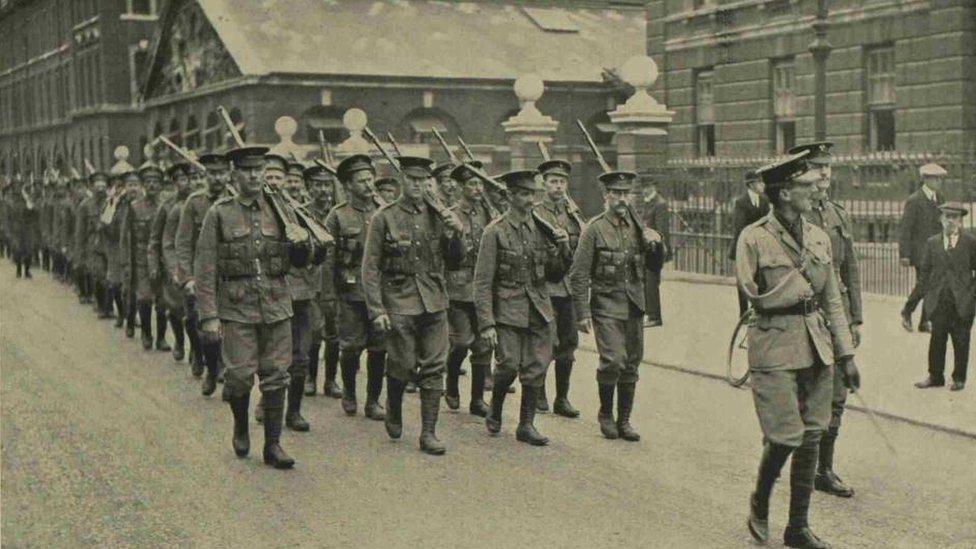

Joseph Heathcote served in the Grenadier Guards in World War One

The Barry War Museum had just reopened after lockdown when a man walked in and made a special donation.

He handed over the medals of Pte Joseph Heathcote, the first soldier from the Vale of Glamorgan town to die in World War One.

Pte Heathcote, of the Grenadier Guards, died aged 21 after just one day of fighting at the Battle of Ypres in Belgium, and was awarded the Mons Star, War Medal and Victory Medal at the end of the conflict.

Along with the medals was a letter explaining how they had come into the donor's possession via his grandfather - an antiques dealer in Chepstow, the town a little over 40 miles (64km) to the east.

Joseph Heathcote's medals: His name is inscribed on the reverse of the Bronze War Medal

Alun Robertson was greeting visitors when the donation was made.

He said: "A well-dressed gentleman dropped off a package of Pte Heathcote's medals, along with a covering letter from a 'Neil Wright', who had apparently received them as a present as a boy.

'When I came back he was gone'

"I turn around to get a donation form to fill in - which we have to do for every donation we receive - but when I came back he was gone."

The letter read: "I was given them in 1969 when I was about nine years old by my grandfather who was an antique dealer in Chepstow.

"Despite extensive research, I have not been able to identify any of his living relatives, so, sadly, it remains a mystery as to why they ended up in my grandfather's shop."

Glen Booker, chairman of the Barry at War Group, said this was not uncommon among donated exhibits.

He said: "In the years which immediately followed WW1 many of the bereaved families, or indeed injured servicemen themselves, were so impoverished that they parted with their medals just to make ends meet - though, especially at that time, they were so commonplace that they had no real value.

"Yet more commonly it happens that the family who have a personal connection just die out, so the medals cease to have any meaning to whoever takes over the estate."

He added: "That's where local museums like ours are so important.

"Maybe many of the items we have wouldn't be of interest to big nationals [museums], but our role is to act as the family of these people, and keep their memories alive long after there's no-one else to do so."

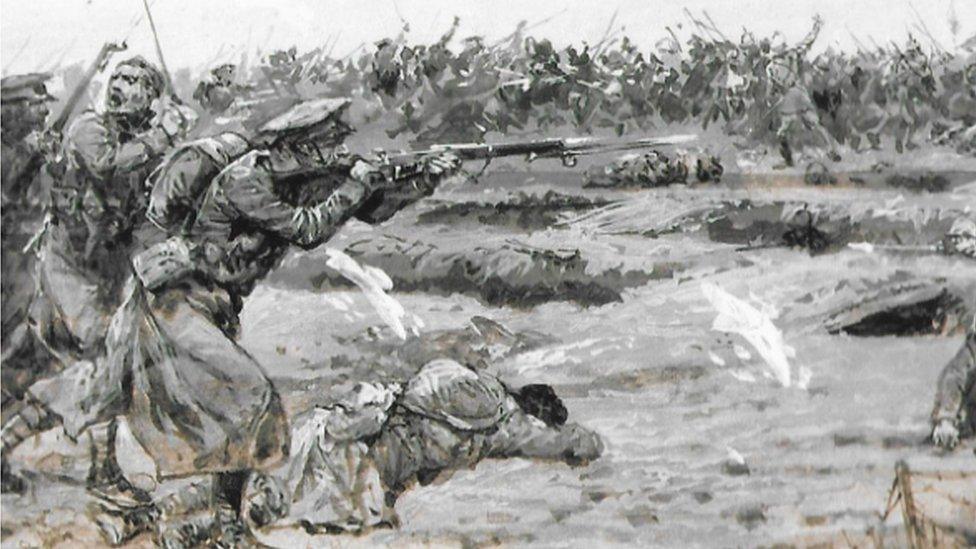

Joseph Heathcote was injured at Nonne Bosschen and taken to a field hospital in Ypres, where he died

Pte Heathcote was wounded at Nonne Bosschen, and died on 29 October 1914, a day after he went into action. That made him one of the first soldiers from Wales to die in the conflict.

It would take a month before his parents, of Amherst Crescent, were told, and another week before it was reported by The Barry Dock News.

'Thousands of men were soon dying'

Rosemary Chaloner, a historian and volunteer at the war museum, said the fact his death was reported individually showed how early it came.

She said: "Sadly, just weeks after Joseph's death there would have been far too many casualties for each to have been reported individually.

"Even though the oft-reported line was that the war would be over by Christmas, in reality thousands of men were soon dying - in Joseph's battle alone there were 54,000 Allied [soldiers] killed and wounded before the end of November."

The war had started in late July, months before Pte Heathcote's death. Ms Chaloner said it was not until this time that fatalities became more commonplace.

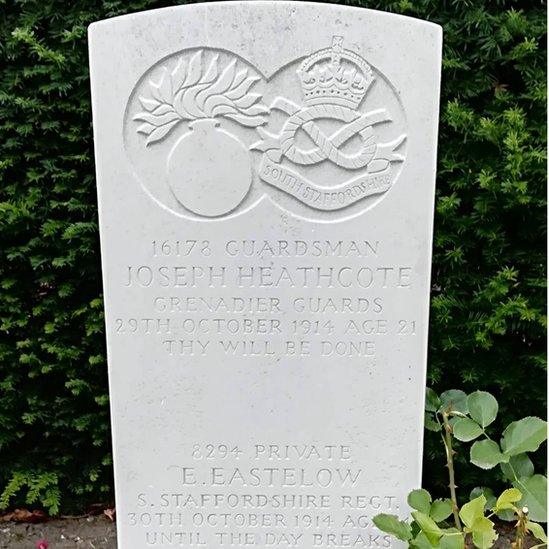

Joseph Heathcote shares a grave in Ypres with Pte E Eastelow

She said there was something of a "phoney war", where armies marched towards each other, when he landed in Le Havre on 13 August 1914.

'Bucolic stroll could not last'

She said: "His first days in France would have been spent passing through some idyllic countryside. Although their British-made boots proved inadequate for the hard cobbled French roads, they must have wondered what all the fuss was about.

"This bucolic stroll could not last, and by October a trench line 475 miles (765km) long would stretch from the North Sea, through Belgium and France, to the Swiss border."

Pte Heathcote is buried in Ypres Town Cemetery Extension, Plot ll, Row A, Grave 43.

He shares his grave and headstone with Pte Eastelow, 1st Battalion South Staffordshire Regiment, who died of his wounds one day later.

"This was a period of the war when the fighting was much more fluid than it would soon become," said Ms Chaloner,

"Deaths like that of Joseph would soon demonstrate the need for entrenchments, which would come to signify the Western Front, and which would lead to the stalemate of the next four years."

Barry War Museum has constructed a purpose-built display case for Pte Heathcote's medals.

Mr Booker said: "He, and all our fallen will never be forgotten, as long as there are people here to keep the museum going.

"We'd love for as many as possible to come and view the medals, and if anyone could help solve the riddle of what happened to them we would be delighted to learn more."

BARGE BASHING AND BICKERING: Explore Welsh canals with Maureen and Gareth

WONDERS OF THE CELTIC DEEP: Encounter mythical coasts and extraordinary creatures

Related topics

- Published11 November 2021

- Published6 November 2021