Recycling: Are soft plastics the final frontier?

- Published

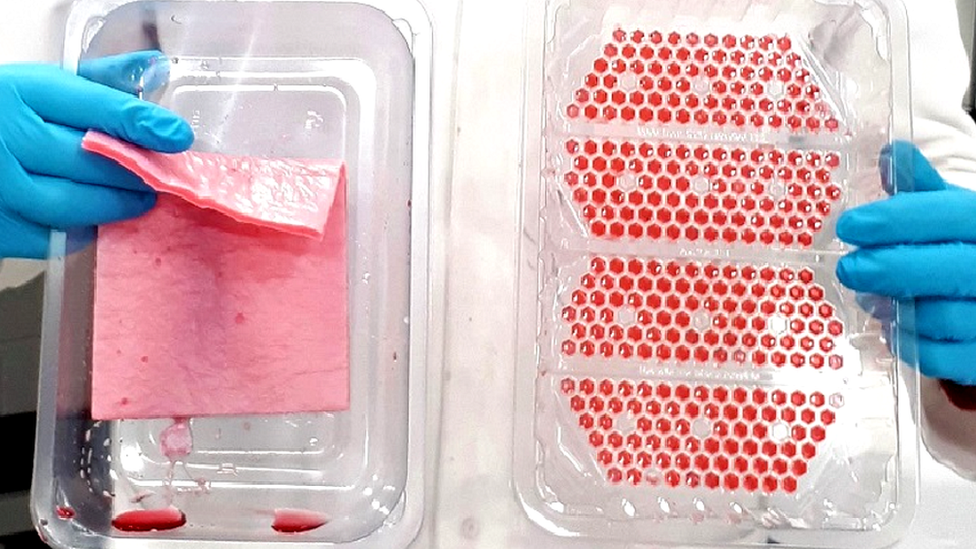

Soft plastics present complex problems to those trying to recycle them

Plastic. It's everywhere these days, even in our bodies. We all know we have to use less and recycle more.

Although we are all used to putting plastic containers into our recycling, what about all those tear-off film lids, bread bags and shopping bags which go into the rubbish bin?

Soft, or flexible, plastic - the kind you can scrunch up in your hand - includes everything from shopping bags to clingfilm. It makes up about 15% of all material which is unable to be recycled at council facilities.

In Wales, just 16% of local authorities collect some plastic film made of polyethylene (PE, commonly called polythene), the material which represents the largest volume of household flexible plastic waste at nearly 40%, according to figures from waste and recycling charity Wrap, external.

Ceredigion and Carmarthenshire are two of those offering kerbside collection of some soft plastics, including shopping or bread bags and toilet paper wrapping, but not items made from multiple materials, such as crisp packets or pet food pouches.

Others, such as Wrexham and Cardiff, offer disposal points at household waste centres, although some will handle soft plastics if it ends up in the recycling by accident.

In some areas, soft plastics can only be disposed of at supermarkets. Tesco, for example, announced in August, external shoppers could take all their soft plastic waste to its large stores - or through community recycling schemes.

Zero-waste store owner Amy Greenfield wants to see plastics recycling "simplified and standardised"

One example of this is Terracycle, external, the industry-funded scheme allowing members of the public to return plastic packaging or other items not currently included in domestic recycling to manufacturers for them to process.

People earn points for recycling which can be given as cash to charities, schools or other non-profit organisations.

Amy Greenfield is a director of Awesome Wales which runs zero waste shops in Cowbridge and Barry in Vale of Glamorgan and hosts Terracycle collection points.

The Barry store has monthly drop-off sessions for people to bring recycling which is collected the same day by a dedicated volunteer, while the Cowbridge site has permanent bins available.

Amy said: "I think a lot of people are really confused about what they can and can't recycle."

Different brands sponsor aspects of the scheme - Walkers runs crisp packet collections and Hovis runs bread bags - other brands can be collected as well, but they have to be very similar products.

Awesome Wales has lots of different containers for its Terracycle recycling efforts (l), including a crisp packet return scheme (r)

"That's why we've got so many different bins and different sections because each item has to be put in separately," she said.

"The main struggle for us is getting people to understand that that's important and basically our waste won't be accepted and our account will be suspended if we just send in whatever people wanted to shove in the bins.

"I think potentially it's a bit too heavily weighted to the consumer and the brands to need to make things simpler."

It would be much easier if there was more standardisation of packaging, according to Amy, with fewer types of plastic used for food packaging and a cut in multi-material products, which are harder to recycle.

"It needs to be simpler, it needs to be kerbside, it needs to be standardised and I think the industry isn't going to do that voluntarily so that's going to require legislation and coordination with local and national government to make sure that happens."

Can we change our behaviour?

Climate change minister Julie James wants producers to take on responsibility for plastic waste

Wales' first Climate Change Minister Julie James is in agreement that the burden of responsibility for managing soft plastics needs to lie with the manufacturers rather than the taxpayer.

She said: "It's a two-pronged approach. We do want to see facilities to recycle soft plastics but our primary push is on trying to stop them.

"We're going to be introducing a 'polluter pays' principle tax on the producers of it," with April as a target, depending on legislative programme issues.

She gave the example of soft film coverings for food products being swapped for a hard plastic lid that can be put back on, as these are easier to recycle, or a switch to something made from cellulose, which is compostable.

"We will be encouraging councils to start collecting [soft plastics].

"There is an issue with kerbside collections about the [refuse] vehicles and how much separate stuff they can actually pick up and, frankly, in many people's houses how many bins you can have exactly?"

Bins like this one in the Co-op accept soft plastic from customers for recycling

Her department has been having "long conversations" with the supermarkets - which the minister calls the biggest procurers of plastic-using products - about giving people more choice.

This includes letting people bring their own containers and filling up themselves, in a much larger version of the zero-waste stores run by people like Amy.

"So it's a combination again. A variable fee, a fine on some products in order to try and get rid of them, and a behaviour change campaign [among the public] at the same time," she said.

There have been discussions looking at opening regional material recycling facilities (known as murfs) which fall into two types: Clean - recycled materials which are then sorted - and dirty- where general black bag waste is taken and separated.

Ever wondered where your recycling goes after it's collected, or why you have to clean it or separate it first?

Ms James said: "There is some possibility that if we had reprocessing purpose for them, we could just let people put all their plastics into one bag and just separate them out at the regional facility.

"If we could centre that at a circular economy point, so somewhere that's generating electricity, near one of our anaerobic digesters because all our food waste goes there and is turned into electricity, if the fleet was electric and being fuelled by the recycling facility, it's a lot more viable."

She also said Wales would move to a system of mandatory labelling on what can and cannot be recycled as " lot of consumers are really annoyed".

"At the moment [with the numbered triangles on packaging] most people think 'that must be recyclable' and put it in, but some of the numbers mean not in the UK, or only in one place in the world."

One of the unintended consequences of a push to reduce plastic use by suppliers could mean making it harder to recycle those that are left, by not having enough to make reprocessing plants commercially viable.

Ms James explained that when food waste recycling was introduced in Wales, ministers had to guess how much processing capacity to allow for in order to guarantee digestor plants, external a certain income.

It turned out people's behaviour altered much more quickly than expected and they stopped producing so much food waste once they could see the volume with their own eyes, meaning the government now pays slightly more in fees because there is less volume than anticipated going through the plants.

How recycling is collected can affect what can be accepted and what is thrown away

Waste and recycling charity Wrap recently ran a 12-week pilot scheme to trial soft plastic kerbside collection in a number of south Wales council areas.

Emma Hallett, from Wrap Cymru's collaborative change programme, said: "In order to collect them effectively we need to ensure they're kept separate from other types of materials so they can be recycled, and also that they don't contaminate the other materials being collected."

The trial helped them understand the type and amount of materials people would put out and how to ensure that, if collection services were offered, materials could be properly collected and recycled.

"It's vital that people put out materials that the council's looking for because the processes that will be followed for recycling will only work with certain types of material," said Emma.

"Although to most people plastic film and wrapping bags might appear to be similar, there are actually a lot of different types of polymers that are used in the manufacture of materials and so each one may need a different treatment according to what it's made of and how it can be recycled."

One of the issues, as Ms James touched on, is that existing collection lorries in council areas that collect recycling in separated containers do not have a section for soft plastics to go in.

Meanwhile, in places where recycling is all collected in one bag or bin - adding soft plastics which cannot be easily separated into the mix risks either contaminating other recycled goods or causing snarl-ups in automated sorting centres' machinery.

However, this has not deterred other places from doing just that - in September the Republic of Ireland introduced soft plastics into its domestic collections, external.

People there are able to add bags and other plastic wrappings to their existing dry recyclables bin, providing all material is clean and dry.

The Irish government's Department of the Environment, Climate and Communications said less than a third of plastic waste packaging was recycled in the country, but it had committed to meeting European Union targets of 50% by 2025 and 55% by 2030.

It added: "There have been advancements in packaging design and investment in recycling technology. This allows segregation of different material types in recycling facilities in Ireland."

Plastics are now brought to recovery facilities and separated out before being sent to specialised, polymer-specific recycling plants. Any that cannot be recycled are sent as solid fuel to replace fossil fuels at cement kilns.

Is plastic all bad?

"Plastic in many cases is better than other alternatives" says waste expert Rebecca Colley-Jones

Rebecca Colley-Jones is the circular economy manager for the Polyolefins Circular Economy Platform (PCEP), a network for all parts of the plastic production and user chain, and a Welsh council member for the Chartered Institute of Waste Management.

"The industry has identified that there is work that needs to be done, that they need to invest not just money but time in developing solutions for these problems," she said.

"For example, there's a number of projects looking at digital water marking for plastics that have been printed, and things like AI [artificial intelligence] is being trialled at plants.

"So that means when the material is captured, more of it can be sorted and go to recycling avenues."

She said there was already a big shift towards using single-material products to enable easier recycling, but added that packaging was "there for a reason", such as providing a seal to make food last longer.

"When you look at the carbon savings improved by having the packaging... it's quite a lot."

She said industry members were "desperate" to be able to recover soft plastics, adding: "They don't want it to go for incineration. They want it to be captured separately, be able to be identified and go back into the system."

Although plastic has definitely had a lot of bad press, rightly at times, it does have a place, Rebecca stressed.

"It's a durable, flexible material and as long as it's captured and put back into use it's not a worse material and in many cases is a better material than other alternatives."

WHAT'S THE BIG IDEA?: Food for the mind, and inspiration for the soul

THE ASIAN WELSH: How immigration from the Indian subcontinent transformed Welsh health, culture and the economy

Related topics

- Published20 November 2021

- Published5 November 2021

- Published5 November 2021

- Published25 October 2021

- Published25 October 2021

- Published29 April 2019