Boxers at greater risk of early onset dementia, study finds

- Published

Peter Flanagan followed his dad and grandfather into the ring - but now wants fighting to be made safer

Men who boxed as amateurs in early life are at greater risk of early onset dementia, according to a new study.

Findings show they are at least twice as likely to have Alzheimer's-like cognitive impairment, with the onset of dementia starting on average five years earlier than those who had never boxed.

Cardiff University followed 2,500 men over 35 years for the study.

The International Boxing Association (AIBA) said research was ongoing around impacts to the head.

It added any changes to regulation would be grounded in "robust research".

The Welsh, English and Scottish amateur boxing associations said that they would fully consider the findings of the study and "significant improvements" had been made in amateur boxing in recent years.

For Peter Flanagan, growing up in a family of boxers, the sport has not just been a career, but a way of life.

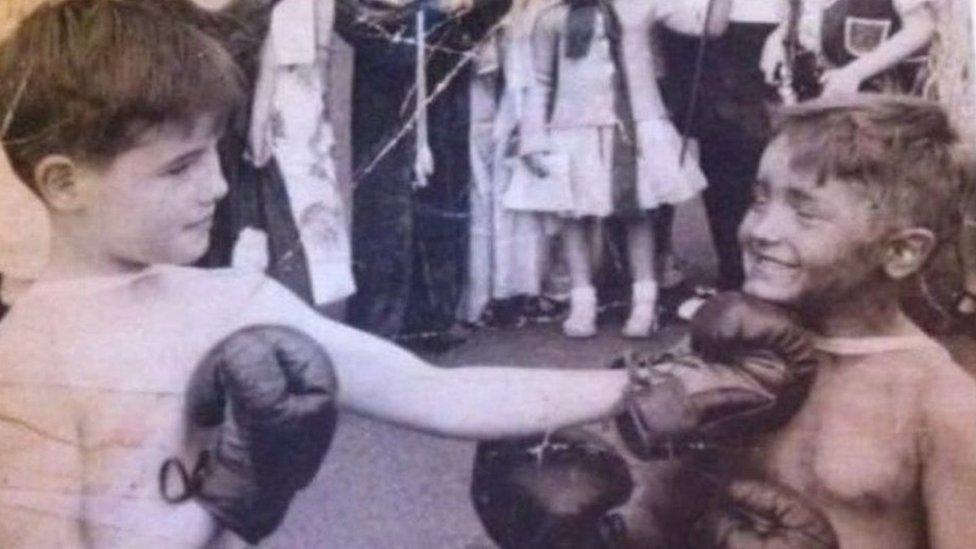

His dad and grandfather both started boxing when they were just 11 years old, and he followed in their footsteps into the ring.

"It's gone on right from the bare knuckle days, the Flanagans were all fighters," he said.

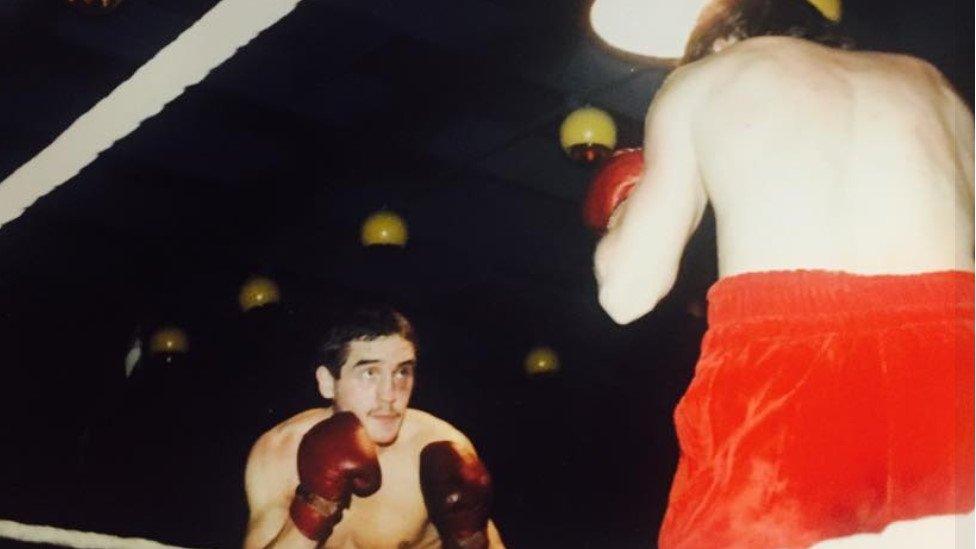

In the 1980s he began a six-year professional boxing career, fighting more than 40 times, and once, four times in 10 days.

But Mr Flanagan, who lives in Glossop, Derbyshire, was diagnosed with dementia four years ago.

Peter Flanagan is fighting dementia by raising money for charity - and walked the Great Wall of China

He described how he was working as a builder when he started to forget things.

"I'd go to the builders' yard, I thought I had everything in my head, but then I'd go back and I'd forgotten vital things," he said.

"Then one day I was driving on the motorway and I just didn't have a clue where I was, where I was going… but within a few minutes it came back."

His daughter Tina said it was frustrating as she noticed his mental health and memory were declining.

"He denied it initially, [he was] very proud… he wanted to carry on being the strong provider for mum," she said.

When her dad was diagnosed with dementia, his consultant was adamant boxing had played a part in scarring his brain.

Mr Flanagan wants to see rules changed to help protect others during training, including limits to head sparring.

Mr Flanagan spars with one of his 11 grandchildren

His short-term memory may be patchy, but his long-term memories of fights remain vivid.

"I got a big punch and from then on I had a big black spot in my vision, I couldn't see him," he recalls of one brutal fight.

"The referee spoke to me, I couldn't see the referee... I went out to the second round and I just couldn't see."

Cardiff University's peer-reviewed study, published in the Clinical Journal of Sports Medicine, is believed to be the first looking at the long-term effects of amateur boxing on the brain.

Author Peter Elwood, involved with the Caerphilly cohort since 1979, described the findings as "very powerful".

Boxing is "in the family's blood", according to Tina Flanagan - dad Peter (right) spars with big brother Andrew in the 1960s

"You collect the information about the factors that you think may be related to dementia or heart disease," he said.

"But you collect it when the men are healthy, they haven't talked to their friends about it, haven't read about it, so very few thoughts are in their minds already and they tell you clearly and, I believe, with total honestly."

Cognitive and psychological tests were conducted every five years on the middle-aged men, who boxed seriously as youngsters.

When they got to between 75 and 90, the medical records were inspected of those with falling cognitive test scores and symptoms.

Anyone experiencing memory loss was seen by a geriatrician and neurologist, before being tested for dementia.

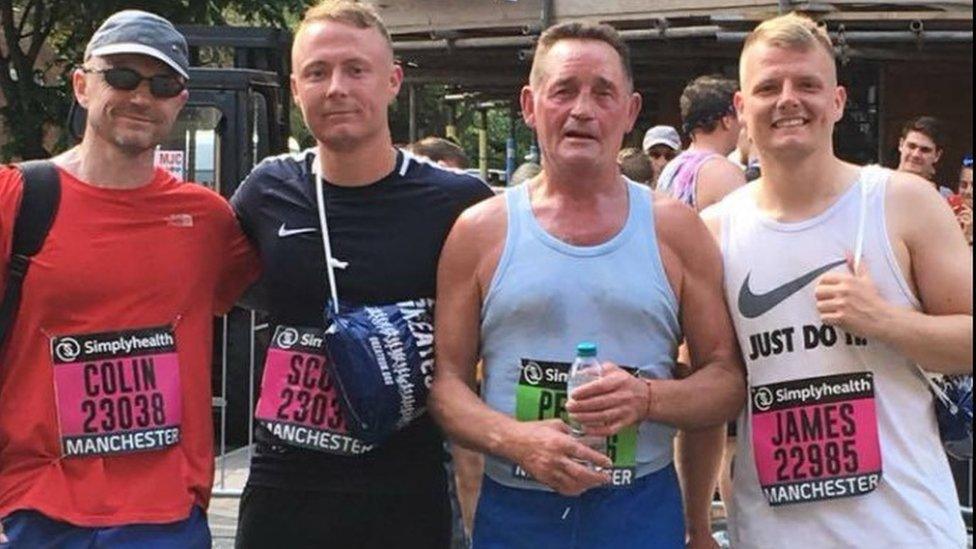

Peter (centre right) has raised money through walking the Great Wall of China, running marathons and sky diving

Prof Elwood admitted being "taken aback" by the results, saying: "The men who had boxed had evidence of a lower cognitive function, of symptoms, of loss of memory, of confusion, and on their tests on their psychological functions."

There was a "threefold increase" of symptoms and signs of Alzheimer's, with the onset of dementia appearing up to eight years and, on average, five years earlier compared with those who had not boxed.

Improvements have been made to boxing since those in the study fought - rounds and bouts are shorter, gloves at amateur level are more padded, with headguards used at some levels.

However, the science on headguards has changed and the governing body no longer uses them at men's senior amateur level.

Mr Flanagan said during his time sparring could be violent.

"Everyone was just trying to knock each other out, it just seemed to be the order of the day," he said.

While he believes training has improved, he wants to see the introduction of limits on sparring to the head during training.

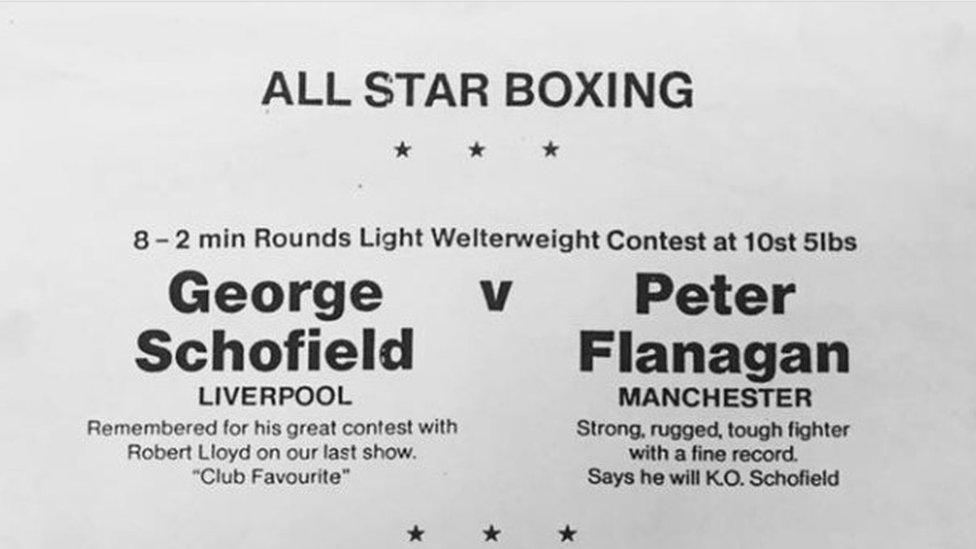

In one fight programme, Mr Flanagan was described as a "strong, rugged, tough fighter"

In a joint statement the Welsh, English and Scottish amateur boxing associations said they were continually working to make boxing as safe as possible.

"No boxer can spar or compete without an annual medical and must have a medical check before and after each bout, while a doctor also needs to be present at every competitive bout at any level, whether in a club show or national championship," it said.

"Any boxer who is suspected of being concussed by a doctor, or where the referee has stopped the bout, is not allowed to compete or spar for 30 days automatically and this is recorded to ensure adherence."

Sparring is also controlled, with pad and bag work now "an important part of training", they added.

Fighting dementia

AIBA said: "As the study makes clear, amateur boxing many years ago in this part of Wales can be linked to cognitive health issues.

"And as the study also makes notes, there have been significant changes since then: in terms of gloves, headguards, contact load in training and competition, and so on."

AIBA added its priority was the health and wellbeing of boxers, and research was looking at impacts to the head.

"Any further changes to regulations and or recommendations on sparring will be grounded in robust research and will be based on our ongoing commitment to boxers and those who support them," it said.

Mr Flanagan keeps busy with his 11 grandchildren and fundraising for charities, including Ringside, which aims to open a care home for retired boxers.

"In a lot of ways I'm maybe in self-denial, but every day I'm convincing myself I'm strong," he added.

"I'm training to fight dementia, like I trained to fight at boxing."

- Published10 November 2021

- Published30 October 2021