Brecon Beacons: Caver trapped for 54 hours relives survival fight

- Published

"One minute I was caving, the next minute the world went mad"

"I kept flipping between two states - there was 'I'm going to fight this and survive', which became, 'I really don't care'."

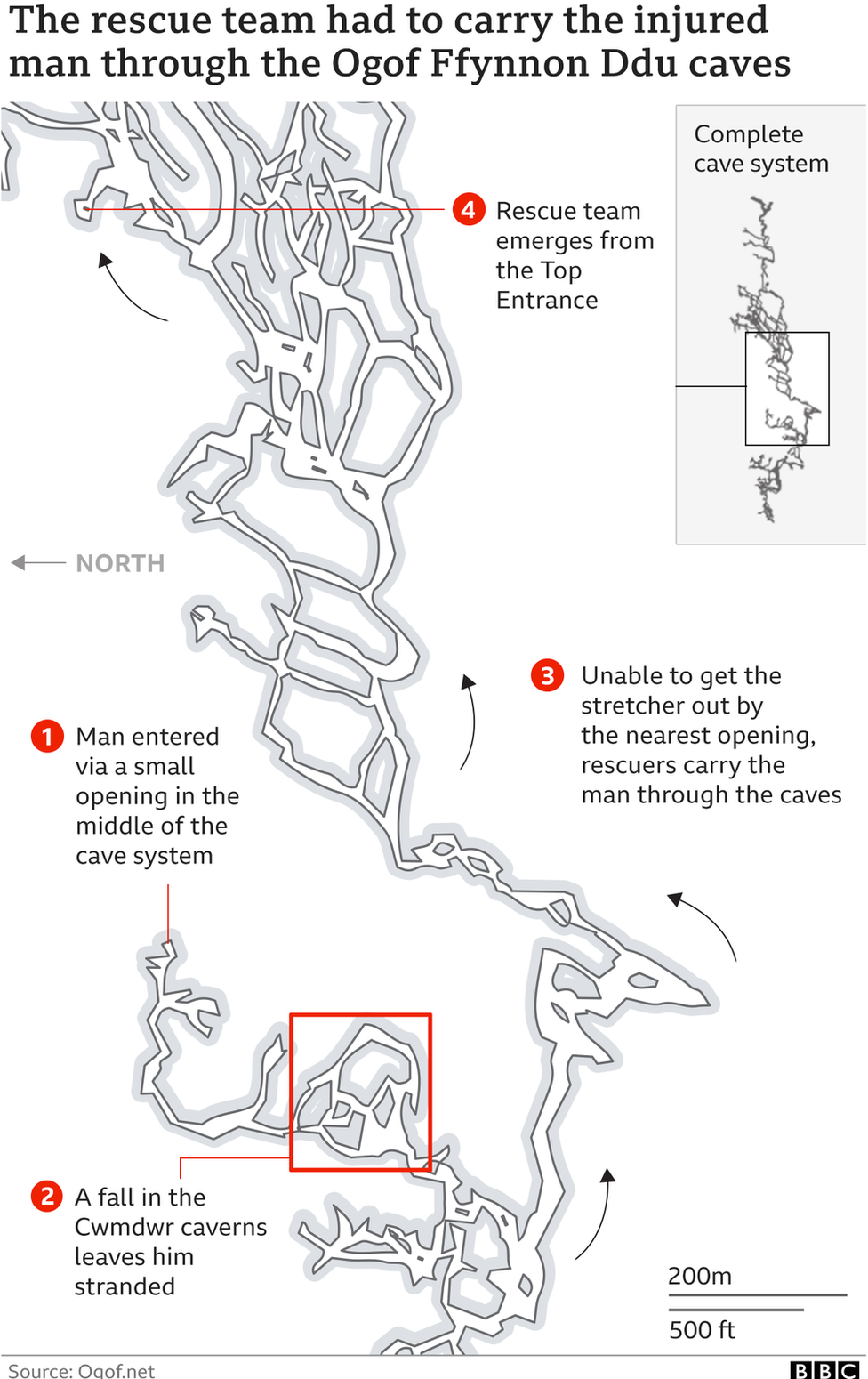

There were dark moments as George Linnane lay in agony, deep in the Ogof Ffynnon Ddu cave system after breaking a leg, his jaw and ribs in a fall.

If hypothermia was not going to kill him, maybe a lacerated spleen or punctured lung could.

"I might never have come out," he admits.

Describing being trapped underground for 54 hours, he said: "One second I was caving, the next minute, the world went mad.

"And then it all went black. And then two minutes later, I woke up in a very different state."

George, 38, has been back to the scene of one of the longest cave rescues the UK has seen, where about 300 volunteers rushed to his aid from around the country.

Feeling "lucky to be alive" and "very lucky" to still have his right leg, he is keen to return to caving and has joined the specialist team that brought him to safety.

"It was meant to be a five or six hour easy trip, out in time for dinner and fireworks," he says of the ordeal that started one Saturday last November.

Perhaps the first question is why a mechanical engineer from Bristol was in a dark, cold complex that reaches about 902ft (275m) below ground near Penwyllt in the Brecon Beacons.

It is one cavers are always asked without ever really being able to answer, he says.

George had started out as a diver and wanted to become a cave diver to access more remote sites.

For this he needed to learn caving, but fell in love with the pursuit in its own right, adding: "When people think of caving, they think of small passages and crawling and misery.

"And that's really not what it's about. We do that stuff. But we do it to get to the good stuff, pretty amazing things that 99.9% of the population will never see.

"It's another world down there. It's like being on the moon or another planet."

He set out in a small group on the morning of 6 November, planning to be out that afternoon.

George has met some of his rescuers, pledging his support as a volunteer

But at some point, deep in the complex that is 61km [38 miles] of twists and turns, an "instantaneous" fall happened, with George having a feeling of "legs whirling around in mid-air, arms grabbing for something".

"At that point, it was pure reflex," he said, before things went blank.

When he came round, it was obvious the bottom half of his leg was broken, there were also teeth missing.

Much of his body felt uncomfortable - at the time he didn't know the seriousness, such as his lower leg displacing itself from the top half, his jawbone being "smashed into a number of pieces" and a large hole that went through to the inside of his mouth.

There were also three broken ribs, a dislocated clavicle with his collarbone pulling away from his ribcage, a lacerated spleen, a collapsed lung and a broken scaphoid in his wrist.

Rescuers entered the system from a small entrance as they tried to get to George

George was upside down on a slope with his legs far higher than his head, and despite the "intense waves of pain", he quickly realised he would need to put himself into a more comfortable position.

Dragging himself by the tips of his fingers for a number of metres, he struggled to turn his body position around.

"I was just screaming and screaming in pain at that point. It was nasty. And then when I got to that point, I also flipped myself from my front over to my back," he said.

"I did this so that I could prop myself up into a sort of semi-seated position and then start waiting it out. And that was agony as well."

His friend Mark checked on him before going to raise the alarm and another friend, Mel, was perched above, fearful of moving a muscle in case she knocked any rocks down on him.

She stood talking to him for hours as they awaited help, although he admits only remembering "bits and pieces".

George says caving is part of who he is and is keen to get back as soon as possible

He recalls giving one-word answers, being told to "wiggle things" to try and keep warm, and to generally stay conscious and "with it".

He describes "dark times" when he would fight, but then give in to a "let whatever's going to happen, happen" state, when he didn't really care and just wished Mel would stop talking.

"It was when those first advanced first aiders turned up, from that point onwards, I always felt like I had a chance. But initially, I wasn't sure I was going to make it."

At this point, he had been underground for four hours and described himself being "quite inwardly-focused", trying to manage the pain rather than thinking how he would get out.

Rescuers took it in turns to hike up the hill from their base and enter the cave system

He remembers hearing voices in the distance and realising they were no longer in his head, but how he was brought to the surface remains "a bit of a blur".

There was the initial assessment and his leg was put in a splint, and then he was offered pain relief but remembers thinking it was not strong enough.

"I basically lost somewhere between 12 and 18 hours, probably towards the 18 hours," he said.

People have told him the first mission was to get him through the narrower passages into the main thoroughfare and a tent to keep him warm.

When he was safely in it, rescuers were also able to give George sugars and liquids through an intravenous line.

After rescuers started arriving, much of the journey out of the cave is a blank for George

He had initially been given energy gel, but his jaw injury had left a hole on his mouth, meaning it fell out before it reached his throat.

But there are a few memories: "Once those initial rescuers turned up, I guess my body went into shock and possibly some sort of hypothermia.

"I then start remembering things again quite a long time later, on the Sunday afternoon, perhaps even the evening."

By this time there were more than 100 people helping with the operation, with about 300 set to join in total, including many familiar faces.

"Once I started becoming more aware of my surroundings again, it became obvious to me that people had come from the Forest of Dean and from the Mendips," he said.

"And then I started seeing faces I recognised from Yorkshire. It just became obvious that people were coming from all over the country."

Cavers had come from all around the UK after hearing about what had happened

At first, he admits to feeling guilty but also incredibly grateful they had come, but perhaps the familiar faces relaxed him to the extent he described the final leg of the journey as "a really, really good experience".

"You enjoyed it, almost in a funny kind of way, I did," he said.

"I'm sure the morphine didn't hurt. If I had been in loads and loads of pain at that point, it probably wouldn't have been.

"We've done a couple of days of the rescue by that point, being strapped to that stretcher backboard being very, very uncomfortable.

"So it was nice to know that it was going to be over at some point."

The sense of relief was compounded by the fact he knew he was on "the home stretch", with the last part a fairly spacious area, with lots of people around him.

His fellow cavers had formed a line and passed the stretcher along with plenty of banter.

There were many familiar faces helping to get the stretcher out of the cave system

There was then an "overwhelming sense of relief" as they got to the exit, and George's first thoughts were of wanting to get off the backboard.

But still strapped to it, he was put straight into the back of a Land Rover and taken down the hill to a waiting ambulance.

His wrist is still strapped up and he will need dental surgery later this year and despite feeling lucky not to lose his leg, there is no doubt he will be back underground soon.

The "single bloody-mindedness" of 300 people to travel from around the UK to help him is one of the reasons.

Their dedication even ran to searching the accident scene for his missing teeth - a task that proved fruitless.

George was eventually taken away in a 4x4 ambulance

"This is one of the things that I love most about caving is the sort of camaraderie in the sense of community that we have, this distinctive thing that we do," George said.

"It creates a really sort of tight-knit bond between cavers."

As well as a sense of gratitude to his rescuers, it is also the realisation that in an accident "there is only one way out" from underground, and his experiences could one day help someone in a situation such as the one he found himself in.

It is with this in mind he has signed up as a volunteer for the South and Mid Wales Cave Rescue Team, which co-ordinated the operation.

Two-and-a-half months after the accident, George is recovering well and hopes to resume his passion soon

He said: "Caving is a very safe sport, generally speaking, for people that know what they're doing.

"It's as safe as crossing a road. But things do happen occasionally. And when they do, there is only one team of people, one type of person that is going to get you out of there.

"The fire service can't do it, mountain rescue can't do it. The only people that can do it is other cavers, because they're the only people with the skill set to do it."

While he describes volunteering as a rescuer as "the right thing to do", there is also another reason he will be back caving as soon as possible.

It is something that perhaps everyone else who has fallen in love with the other-worldly experience can relate to.

"I'm a caver and I'm a diver," George said.

"It's what I do and what makes me happy. And I know that whilst something bad did happen to me, the chances of it happening again is very, very low.

"Let's hope so. I don't think I would be happy if I didn't go back to it."

BARGE BASHING AND BICKERING: Explore Welsh canals with Maureen and Gareth

DIG OUT YOUR CAGOULE AND TIE UP THOSE BOOTS: The Welsh Coast awaits, explore it with Derek

Related topics

- Published10 November 2021

- Published8 November 2021

- Published8 November 2021