Identity: What does it mean to be Welsh?

- Published

Two writers share their experiences of being Welsh when your appearance "does not match an accepted aesthetic of Welshness"

Rugby, rolling hills, castles, coal and choirs - these are some of the images often associated with Wales and the Welsh.

But what are the experiences of Welsh people who have plural ethnic and cultural identities?

What preconceptions might a black child face in rural Powys or a hijab-wearing Muslim face in Cardiff?

Welshness should be seen as "a spectrum rather than a hierarchy... a patchwork quilt", said writer Hanan Issa.

She is one of a number of contributors to book Welsh Plural, a collection of essays "on the future of Wales" that offers "imaginative, radical perspectives that take us beyond the clichés and binaries that so often shape thinking about Wales and Welshness".

Writer Kandace Siobhan Walker and her family moved to the Brecon Beacons when she was a child

Writer and filmmaker Kandace Siobhan Walker, 27, said when she and her family moved from east London to Brecon Beacons National Park, Powys, in 2003 they were "poster children for multiculturalism, for globalisation".

From the age of nine until she left for university at 18, home was a remote house at the end of a bridleway.

She said it was difficult finding anyone who knew how to work with afro-textured hair so a hairdresser from over the border in Hereford would travel to see the family at home, her mother, who remains in the family home, found a man in Bristol who could order in Jamaican ingredients, and finding somewhere that stocked her favourite Caribbean drink sarsaparilla was a regular mission.

Kandace and her family, pictured in 2003, shortly after their move to Wales

'Why is she here?'

In her essay, Lights in the Dark: Notes towards a personal history of Wales in the 21st Century, Kandace writes about being "tolerated nowhere, questioned everywhere".

Asked about what experiences led her to write those words, she recalled a time when she was 14 and a woman stopped her in a supermarket carpark.

"She asked me what tribe I was, I was like, 'what you're talking about?'," she said.

She said hikers were often surprised to see a young black girl in the rural Welsh hills: "Even if I was just in my own garden, walkers would be thinking I'm another walker - and I'm like, 'I'm in a dressing gown'.

"There's that implicit idea, 'why is she here?'"

Writer Kandace Siobhan Walker says she has hope and pride in Wales and Welsh culture

'Where are you from?

She also writes about the "everyday dispossession" of white strangers asking 'where are you from?' - "a classic".

"It's a very loaded question and I think people know that," she explained.

"'You come from somewhere else, maybe your family comes from somewhere else, or like your ancestors do' they know that history is fraught and so it feels often quite entitled... 'what trauma do you come from? Like, what's gone on there?'"

She said by the time she got into her 20s she started simply saying, 'I'm from here'.

"I don't want to get into it with strangers usually."

Kandace Siobhan Walker says white walkers would often assume she did not live in the rural Brecon Beacons

She said when a black person asks the same question "it's almost always a completely different conversation because they're going to tell me where they're from".

"It's more like an excitement, we're going to compare, take out our little family histories and be like 'look how kind of similar bit different they are'."

She said white people who ask her where she is from have usually "decided their history is kind of ubiquitous and uninteresting that they don't need to explain themselves to me".

Kandace, who now lives in south London, said she wrote her contribution to the book at a time when she was thinking more about "purposely identifying as Welsh" and "who decides that".

Kandace Siobhan Walker lived in Wales between the ages of nine and 18

"What happens if I start telling people I'm Welsh and just letting them argue it out for themselves," she said.

She said for a long time she was "trying to let it not matter too much where I came from, or who I came from in terms of people - but eventually I just realised it was such an integral part of my life - my dad's family are African American and my mum's family are Jamaican Canadian...

"We moved to London but then moved to Wales so we've never fitted into a specific like pattern or group in terms of eras of migration."

She said through her writing she had realised "how much it meant to me to have grown up in Wales and be Welsh".

"I think Wales is just a fundamentally plural place, a place built on pluralities in its history and its culture and its language," she said.

"Despite kind of negative experiences I've had growing up, or even now, I always have hope and quite a lot of pride in Wales and Welsh culture."

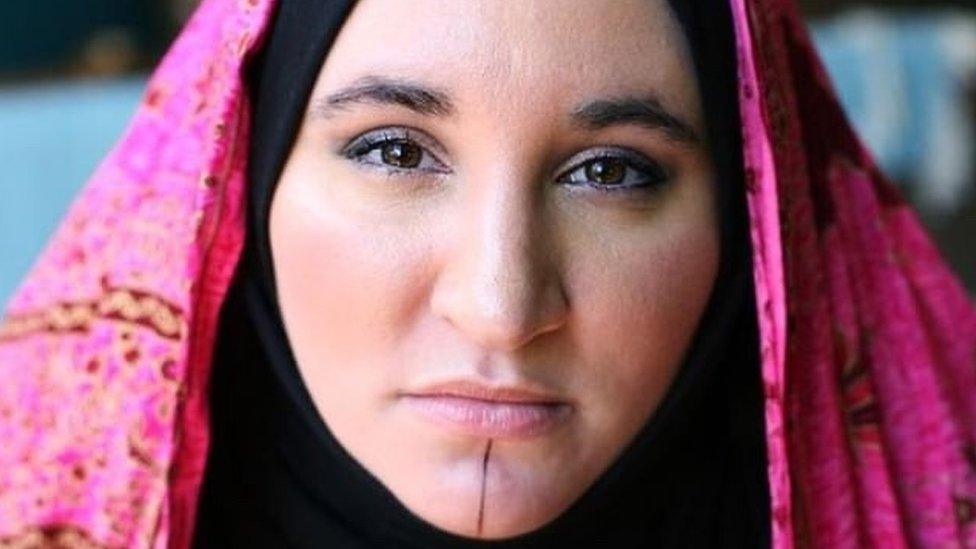

Writer Hanan Issa says people's perception of Welshness is too narrow

Writer Hanan Issa, 35, from Cardiff, said is was a discussion about the "frustrations of how narrow the perception of Welshness is" at the Hay Festival with three other Welsh writers that eventually led them to work on the book.

She said she had always had a "plural perception of identity".

"I'm mixed race, I've got Welsh heritage and Iraqi heritage," she said.

She said people had sometimes assumed she was not Welsh because of her appearance.

"Not so much recently, but you know I have had experiences where people will say things like 'oh your English is very good'.

"It doesn't work, this idea that you have to look Welsh."

In her essay - Have you heard the one about the niqabi on a bus? - she recalls times people have "faced abuse because their outward appearance doesn't align with people's perception of Welshness".

She writes about the time her white mother, who was wearing a niqab, was abused by a man in Cardiff indoor market.

"Looming over her, he shouted in a Cockney accent, 'Why don't you go back to your own country'.

"Without missing a beat my little nan squared up to this bully saying, 'she's my daughter and she's Welsh but you are not. Why don't you do us a favour and go back to your country?'"

She concludes the anecdote: "While it is a story of triumph, Nan's defence relied on my mum's white Welshness to emphasise her right to belong here."

Hanan says some people have sometimes assumed she is not Welsh

Hanan said there was a "very strange, luminous space between being seen as something foreign but having all these experiences that were very Welsh".

So, what does it mean to be Welsh?

Hanan said an integral part of Islamic faith is "khalifah", meaning caretaker.

She wrote: "Perhaps Wales and Welshness belongs to all those who care for her and the people who call her home."

THE STORY OF MIWSIG: Eleri Price and Huw Stephens time travel with Welsh language pop

MARGINS TO MAINSTREAM: Michael Sheen introduces new writers revealing their truths

- Published20 October 2021

- Published4 March 2021

- Published22 February 2022