Operation Mincemeat: The Welsh drifter who helped end WW2

- Published

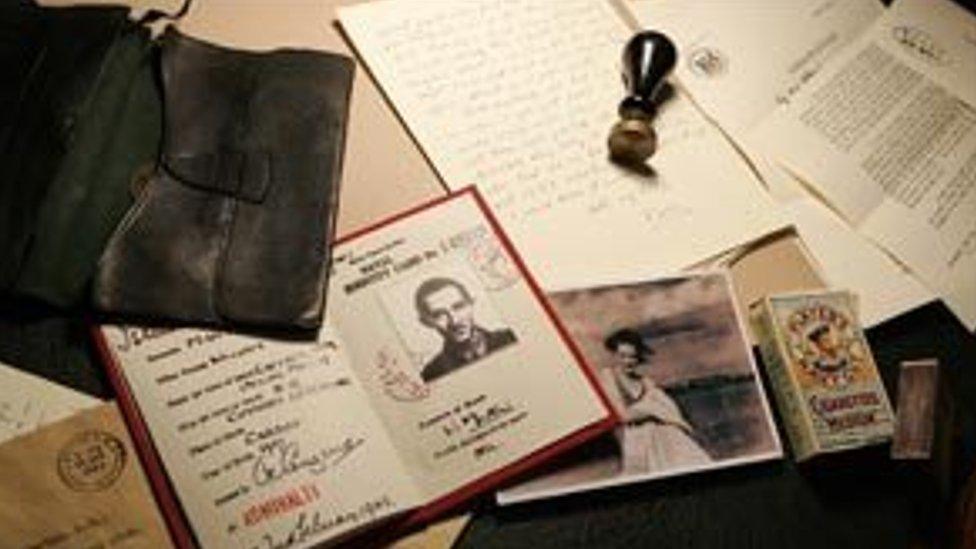

Glyndwr Michael's body was given a fake identity as Acting Major William Martin

"The only worthwhile thing that he ever did, he did after his death."

British intelligence agent Ewen Montagu's view of Welshman Glyndwr Michael may be somewhat harsh.

After all, after his death aged 34, he helped to end World War Two months earlier than it could have ended, saving hundreds of thousands of lives.

In April 1943, his corpse was used for Operation Mincemeat, the most audacious hoax of the conflict.

It duped the Germans into redeploying entire regiments away from Sicily to Greece and the Balkans.

Historian Ben Macintyre's book, Operation Mincemeat, has now been made into a film by Warner Brothers and is due for release on Good Friday.

"Glyndwr Michael is possibly the most unlikely hero of the entire Second World War," he said.

"He ran to London to escape incredible poverty during the Great Depression of the 1930s, which resulted in his father's own suicide after the collapse of work in the mines."

A coroner's report says Glyndwr Michael took his own life by taking poison, but historian Ben Macintyre believes he may have mistakenly eaten rat poison

Mr Macintyre said Mr Michael's body was found in a warehouse in King's Cross, London, with a coroner's report saying he had taken his own life by taking poison.

"But I contest even that; I believe he may have been so hungry that he even ate poisoned bread left out to kill rats," he said.

Straight out of a Bond novel

Whatever the cause of the death of Glyndwr Michael, who was from Aberbargoed in Caerphilly county, the vagrant's body was soon handed over to London coroner Bentley Purchase, who had been placed on high alert for a body whose injuries would not be inconsistent with having fallen out of an aeroplane with a failed parachute.

Once in the hands of agents Charles Cholmondeley and Ewen Montagu, the transformation into Acting Major William Martin began.

While Glyndwr Michael was kept in a mortuary refrigerator, agents Cholmondeley and Montagu set about creating his fake identity

It was a plan first conceived by James Bond writer Ian Fleming in the 1930s: use a dead body to float false plans into enemy territory.

By late 1942, success in the North African campaign had allowed the Allies to turn their attention to the "soft underbelly" of German-held Europe.

Sicily was the obvious launch point, since control of the island meant control of shipping in the Mediterranean.

The problem was, it was too obvious.

The man who never was

"Everyone but a bloody fool would know that it's Sicily," said the then prime minister Winston Churchill.

That did not stop the Allies wanting to take Sicily though, as a stepping stone to Italy. So they needed to pull off a spectacular act of misdirection.

A briefcase full of fabricated military secrets was chained to his arm

So Glyndwr Michael became Acting Major William Martin, chock-full of fabricated military secrets chained to his arm in a supposedly unbreakable briefcase.

With Mr Michael kept in a mortuary refrigerator, Cholmondeley and Montagu got to work on the details they were certain would make the hoax more believable to the Germans.

They gave their fake officer an exhaustive identity and backstory, beginning with the name William Martin, a common surname in the Royal Marines, and the rank of Captain (Acting Major), which they deemed high enough to carry top secret documents, but not so important that the enemy would know him.

Then came the "pocket litter" - everyday items anyone would have on them. In Martin's case, this meant keys, stamps, cigarettes, matches, a St Christopher's medallion, theatre ticket stubs, a receipt for a new shirt, a letter from his father, and even an overdraft notice from Lloyd's Bank.

These had to be written in special ink so as not to run while in the water.

Ewan Montagu spent months fleshing out the fake officer

But Ben Macintyre maintains that the most convincing part of the puzzle was Martin's fiancée Pam.

"The level of detail they went to was incredible: including wearing the supposed Martin's uniform and underwear so it would seem worn to the right extent.

"I was lucky enough to meet 'Pam' (Jean Lesley), in her 80s, and she took me down to the Thames to the point where she and 'William' had supposedly got engaged. We could all believe it - so good was the story that even Montagu's wife became convinced he was having an affair."

The deception

Cholmondeley and Montagu prepared the body and loaded it into a container filled with dry ice for the journey to Scotland; the vehicle was driven by a pre-war motor racing champion.

The submarine HMS Seraph was waiting. It took 10 days and two enemy bombings to reach the drop-off point.

All the while, the crew was unaware of the purpose of its mission. Once the officers lowered Martin into the water, the engines revved so that the wash would push it towards the Spanish shore.

Glyndwr Michael's body was discovered by a sardine fisherman off the coast of Spain on 30 April, 1943

Early on 30 April, 1943, a sardine fisherman came across the supposedly drowned British officer near Huelva, Spain.

The German military intelligence, the Abwehr, fell for it hook, line and sinker, and a copy of Martin's letters for the plans of a Greek invasion landed on Adolf Hitler's desk.

Meanwhile, in a dim, smoky and cramped basement room of the Admiralty in London, the men and women of British intelligence banged the tables and jumped up and down when the message to Hitler was intercepted by Enigma code-breakers at Bletchley Park.

Final Welsh connection

Mr Macintyre said there was a final Welsh connection which may have eventually convinced Hitler that the body was genuine.

"One of the letters from Martin's father was supposedly written from a hotel in Mold," he said.

"When researching my book I went back to the original register, and would you believe it? There was a Mr Martin penned in on the correct date of the letter; the depth of the back-story is incredible."

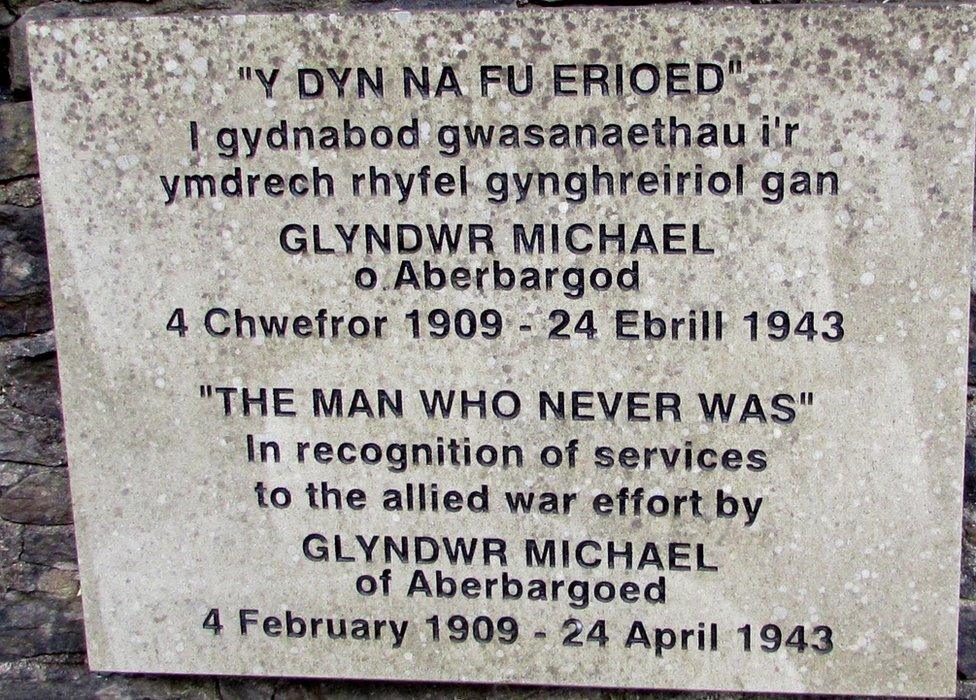

A plaque memorialises Glyndwr Michael as "the man that never was" in his hometown of Aberbargoed

The British followed up their deception with an easily intercepted telegram to the Spanish, asking for the return of Martin's briefcase as soon as possible.

"Secret papers probably in black briefcase. Earliest possible information required. It should be recovered at once. Care should be taken that it does not get into undesirable hands."

Within 38 days of the Allied invasion of Sicily on 10 July 1943, the island had been captured, and shortly after Italy fell, bringing about the downfall of Benito Mussolini's regime.

Glyndwr Michael was buried in Huelva, in Spain, with full military honours.

Related topics

- Published6 February 2022

- Published13 March 2022