Logan Mwangi murder: What should happen to children who kill?

- Published

Craig Mulligan has been named as the 14-year-old boy involved in the killing of Logan Mwangi

A "complete shift" is needed in the way we deal with children who murder, a campaigner has said.

A 14-year-old boy and two adults were given life sentences for murdering five-year-old Logan Mwangi.

Dr Tim Bateman wants shorter maximum terms, children held in secure childcare establishments and the age of criminal responsibility, external raised to 16.

The Ministry of Justice said it was committed to trialling secure schools, external as a new model of youth custody.

Logan's mother Angharad Williamson, 31, his stepfather John Cole, 40, and Craig Mulligan, 14, killed Logan in July 2021, in a "brutal and sustained" attack at home in Sarn, Bridgend county, leaving him with "catastrophic" injuries.

His body was dumped in a nearby river.

Cole will serve a minimum term of 29 years in prison while Williamson will serve at least 28 years, after being found guilty of murder following a trial at Cardiff Crown Court.

Mulligan - who is not the biological son of Cole but was raised by him from the age of nine months - will serve at least 15 years.

Jon Venables (left) and Robert Thompson murdered two-year-old James Bulger in 1993

The age of responsibility

In many other countries around the world, Mulligan would not have come to court because his age would prevent him from being prosecuted for any crime, said Dr Bateman, chair of the National Association for Youth Justice.

The age at which children are regarded as responsible for their actions in law varies across Europe - from 10 in Wales and England through to 14 in Germany, 15 in the Netherlands and 16 in Portugal.

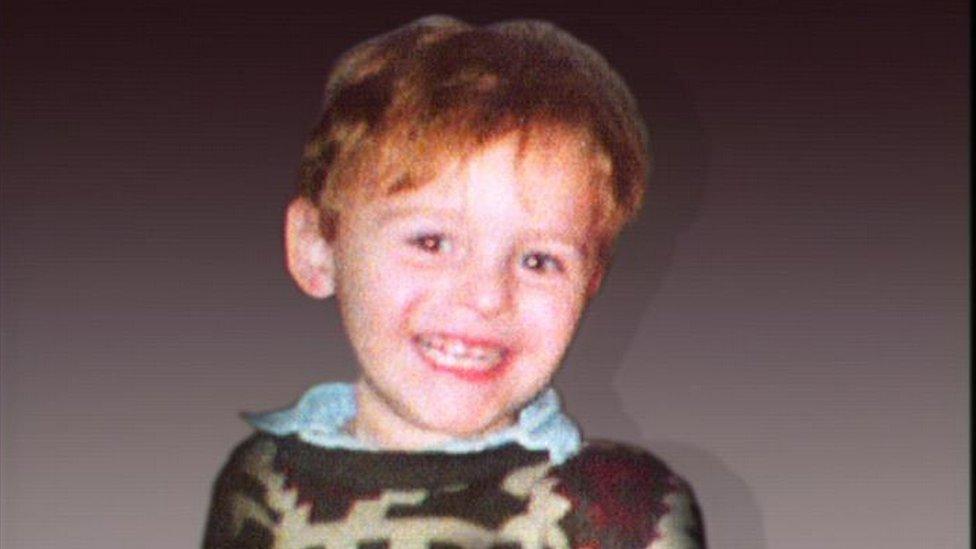

James Bulger was abducted from a shopping centre, tortured and murdered by two 10-year-olds in 1993

The youngest convicted murderers in modern British history are Jon Venables and Robert Thompson, the 10-year-olds who in 1993 abducted, tortured and murdered two-year-old James Bulger.

They were jailed for life but released on licence with new identities in 2001.

The year after James' murder, five-year-old Silje Redergard was beaten by two six-year-old boys and left to freeze to death in the snow in Trondheim, Norway.

But in Norway, no children under 15 are prosecuted and Silje's killers were left with their families, helped by psychiatrists and social workers and were back at kindergarten within a week, external.

Recalling the public outrage that followed James' murder, Lawrence Lee, the solicitor who represented Venables, said: "I don't think society could get their heads around how this kind of thing could happen."

He said the scenes outside the court, where people hurled bricks at the prison van, would "live with me forever".

Hundreds of toys, teddy bears and flowers were left in Pandy Park after Logan's body was found

When asked if he thought children should be held responsible for crimes such as murder, he replied: "Yes, I think, nowadays, more and more...

"Children now are much more aware, they are so aware of their rights... a lot of children are so streetwise they purposely hide behind the veil of anonymity, because they know they're not going to be named."

He believes it is correct to try children in court: "There's no way that these defendants can go free and they've got to be punished, but they've got to be educated as well if that's possible," he said.

Mr Bateman said had Venables and Thompson been a few months younger they would not have faced prosecution, but would most likely have been taken into care and placed in a secure children's home for a significant period until they were assessed as safe to release back into the community.

"The same end would have happened without going through the criminal justice process," he said.

"The negative connotations of criminal conviction and media identification could be avoided."

Dr Tim Bateman would like to see a shift in the way Wales and England deal with children who commit murder

"We have a rather odd situation in England and Wales in relation to children who commit murder," said Dr Bateman.

"For instance, if you think about smoking - an adult can choose whether or not they wish to smoke... if they wish to damage their health [but] we don't take that view in relation to children who can't buy tobacco until the age of 18 because we don't regard them as fully responsible - they can't be trusted to take full account of the long term implications.

"To a large degree, when children break the law those assumptions go out of the window and suddenly we attribute full responsibility to children."

'Complete shift'

Dr Bateman said he wanted to see "a complete shift in the way that we deal with children who commit murder", including releasing them "when there is still plenty of opportunity for them to make the transition to adulthood in a relatively normalised environment".

He said: "We're one of the only countries in Europe that has an automatic life sentence for children who commit murder."

Detention during Her Majesty's Pleasure, external is a mandatory life sentence imposed when a child or young person is convicted or pleads guilty to murder.

The starting point for determining the minimum sentence where the offender is under 18 is 12 years and 15 years for those over 18.

"I would like to see a much shorter maximum sentence available for children, as happens in many other parts of the world," he said.

But Mr Lee has faith in the current system: "[We should] trust the parole board that they will not release that child until they are fit for return to society," he said.

"There could be serious consequences if they're released too early and they reoffend."

A Ministry of Justice (MoJ) spokesperson said: "While it is for independent judges to decide sentences, we have changed the law for children who commit murder so that judges have a range of starting points that account for the child's age and the severity of the murder."

'Increase prospects'

About 75% of children who receive a custodial sentence go to young offenders institutions which are "very, very similar to adult prisons", Dr Bateman said.

A smaller number go to privately managed secure training centres and others go to secure children's homes.

Logan's mother Angharad Williamson and stepfather John Cole were found guilty of his murder in April

There are 14 individually managed secure children's homes throughout Wales and England, which restrict children's liberty to ensure their safety while providing care, education and support.

Local authorities can place children there if they are deemed to be a significant risk to themselves or others and the Youth Custody Service can place children who have been remanded to custody or are serving a custodial sentence.

Dr Bateman also wants an end to young offenders institutions, and all children who receive a custodial sentence held in childcare establishments.

"There are higher levels of staffing, support is much more thorough, there are opportunities for therapeutic interventions, capacity to work with the child towards their release, engage them in education and training and massively increase prospects for them in later life," he said.

Mr Lee said that whatever type of facility a child was held in they must have a "proper education, proper upbringing, so that eventually the chances of him being returned to society in a fit state is enhanced".

An MoJ spokesperson said: "We are committed to trialling secure schools as a new model of youth custody that embeds education and health at its heart to reduce reoffending."

Solicitor Lawrence Lee represented Jon Venables at the trial for James Bulger's murder in 1993

What about anonymity?

In the Logan Mwangi murder trial, Judge Mrs Justice Jefford granted anonymity to the 14-year-old defendant through section 45 of the Youth Justice and Criminal Evidence Act, external.

However, these restrictions were challenged by the media at sentencing, and the judge lifted the order, meaning on Thursday he could be identified for the first time as Mulligan.

At the trial of Venables and Thompson, the judge lifted reporting restrictions, saying: "The public interest overrode the interest of the defendants."

In 2001, they were granted new identities and lifelong anonymity when they were released on licence.

A court order banned anyone from revealing their new identities.

In 2015, a judge lifted reporting restrictions on the naming a 15-year-old boy who murdered teacher Anne Maguire in Leeds.

Mr Justice Coulson said identifying Will Cornick was in the public interest and would have "a clear deterrent effect".

Dr Bateman said: "The fact that we can identify children is something which is out of step internationally."

Logan was found dead in the River Ogmore in Sarn, Bridgend county, last July

He said naming could encourage vigilante behaviour, not just against the child defendant but also their siblings and the wider community.

He said it could also be detrimental to the defendant's rehabilitation: "If they wake up and see their picture on the TV, on the front page of the newspaper as a child murderer that will have a significant impact on their development, the way that they see themselves, in my view, is likely to increase the risk that they will continue to be a danger to others."

He said it would also have a negative impact on them after being released: "Employers will be much less likely to offer opportunities to children who have been all over the front pages of the newspapers, colleges will be much less likely to offer places to such children."

Mr Lee said he saw both sides of the issue: "I would have grave misgivings about naming but on the other hand, I'd have grave misgivings about remaining anonymous...

"I could understand a judge saying 'right, well let's name them and if we can save a teacher's life, if you can save any victim's life, it's worth it'.

"On the other hand, they will be thinking 'well if I do name, he is it going to be a target for revenge'."

Normal life?

How Logan Mwangi's killers tried to fool police

When asked if Mulligan could ever have a normal life, Dr Bateman said it would be difficult.

"It will be difficult to come of age, to make the transition to adulthood in a custodial institution and not spend your time, as most adolescence do, learning how to deal with the wider world, learning how to be an adult."

Mr Lee is more optimistic: "It depends on whether or not they're branded evil," he said.

He said excursions outside prison would be essential towards the end of his sentence: "If he is kept in custody for 10 years, unless he has the opportunity of dipping his toe into real everyday life, I think his chances of being normal again are very slim."

- Published22 April 2022

- Published21 April 2022

- Published23 April 2022

- Published21 April 2022

- Published22 April 2022

- Published21 April 2022