Pembroke: Archaeologists hunt for Ice Age life under castle

- Published

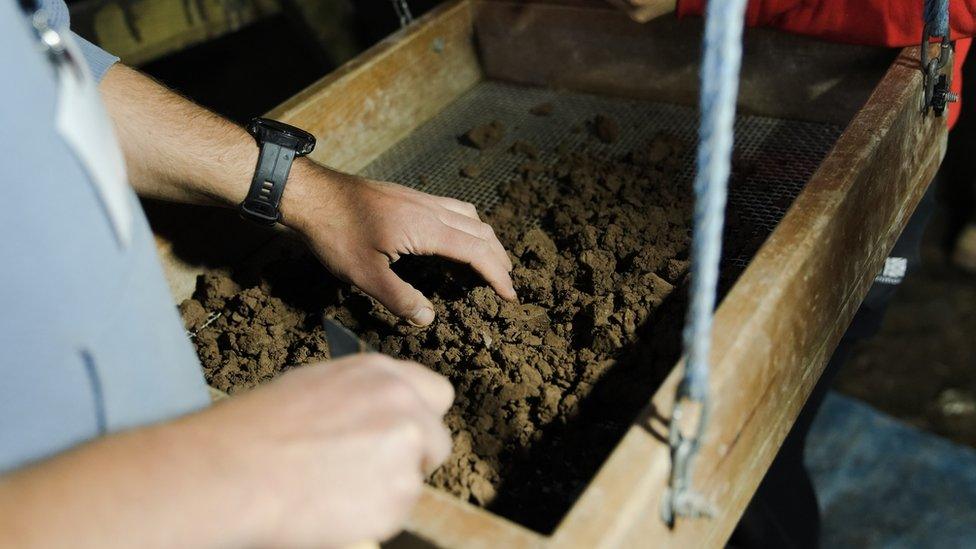

Reindeer and mammoth remains have been among the Ice Age artefacts unearthed by the team

Archaeologists have made discoveries which could be fresh evidence of life during the Ice Age during a dig under a town's castle.

They focused on areas of Pembroke Castle's Wogan Cavern that have remained undisturbed for more than 10,000 years.

Dig leader Dr Rob Dinnis said the team hoped to "come back and dig some more" after their "promising" finds.

The material now needs to be verified and dated.

A small team visited the cave last summer and found hints of early prehistoric material, including reindeer and woolly mammoth bones.

Although limited in size due to Covid-19 restrictions, the dig unearthed enough evidence of early human occupation to establish the cave as nationally important for the Mesolithic period - about 10,000 years ago.

Dr Dinnis and a team of 15 to 20 archaeologists returned on 27 June to look at how it was used by Stone Age humans and prehistoric animals.

A week-and-a-half into their three-week dig, the team have made a range of discoveries.

The material discovered will now need to be verified and dated

However, much of the cavern has not been explored and there is the potential for more work to be done.

The dig was funded by the Natural History Museum and the British Cave Research Association and follows longstanding interest in the cave by archaeologist John Boulton of the Devon Speleological Society, after visiting the site during a family holiday 10 years ago.

"What we're really looking for is human occupation during the Ice Age," he said.

"We've found that the cave deposits extend much further than we previously thought and that doesn't happen in Britain anymore - the caves have just been emptied."

Dr Elodie-Laure Jimenez, of the University of Aberdeen, added that it was a "unique chance" to explore what happened in the cave during the prehistoric times using the latest lab-based methods.

"We have the chance to understand a bit more about who lived in this cave, what kinds of animals and humans even, and when," she added.

John Boulton became interested in the site after visiting during a family holiday

According to Dr Dinnis, of the University of Aberdeen, much of the cave remains unexplored by modern archaeologists.

"It has long been assumed that the cave was dug out, either during the medieval period when it formed part of the castle, or during the very poorly recorded Victorian digs.

"Our work shows that is not the case. It's a promising site with potential. We've only dug two areas this time and we want to know if other parts of the cavern have items to discover."

Dr Dinnis said the team would "love to come back here and dig some more".

SAM SMITH PRESENTS STORIES OF HIV: From Terrence Higgins to today

LIFTING THE LID ON THE CARE SYSTEM: A shocking insight into the lives of young people in care

Related topics

- Published25 April 2022

- Published18 April 2022