April Jones: Is the internet safer after April Jones' murder?

- Published

April's tragic case has made a difference in protecting children today, says the Internet Watch Foundation

April Jones' murder brought policies that were "game-changers" in protecting children, says one regulatory body.

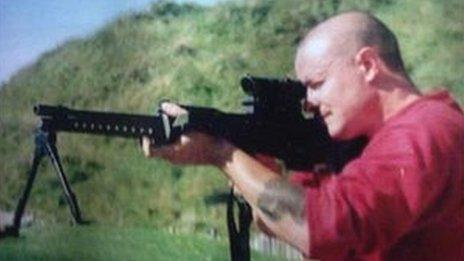

April, five, from Machynlleth, Powys, was abducted and killed in 2012 by Mark Bridger, who had a mass of child abuse images on his computer.

Her parents pushed for change and the Internet Watch Foundation were given powers that has since seen them remove millions of images.

The organisation said it was a "wake up call" but they continue to face issues.

They said with being able to identify and remove abuse, they have found a "national crisis" around children being tricked into filming themselves at home, meaning they are more vulnerable than ever.

April Jones went missing on 1 October 2012 near her home, sparking the largest search in British police history.

She was abducted and killed by local man Mark Bridger, "a dangerous fantasist" and paedophile who received a whole life sentence for her murder.

A library of child sex abuse images were found on his computer, and evidence of search terms including "naked young five-year-old girls" as well as pictures of murder victims including the Soham victims Holly Wells and Jessica Chapman.

He also had Facebook pictures of local young girls, including April and her sisters.

April's remains have never been found.

April's parents have been campaigning since her death for stricter laws surrounding sex offenders in order to protect children.

Following a campaign by her parents who said police were not doing enough, the then prime minister David Cameron granted the IWF additional powers in the UK to scan for and remove abusive images, working alongside law enforcement.

Mr Cameron was vocal after her initial disappearance, branding it "a parent's worse nightmare", particularly as she had cerebral palsy like his son.

He said about reforming methods of searching for material, he wanted to "look her parents in the eye" and have helped.

'A wake up call'

April Jones' family's campaigning has helped protect other children, says Susie Hargreaves of the IWF

Ten years after April's death the chief executive of the IWF, Susie Hargreaves said the powers granted to them following April's murder were a "game changer" in internet safety.

She said April's death was a "wake up call" and she praised the "bravery and courage" of April's family "to do everything they could to ensure it would not happen to any other children".

Ms Hargreaves said: "It meant that we were able to massively increase the amount of images and videos of child sexual abuse we were able to take down from the internet, and I don't think that would have happened without the tragic events around April's death."

At the IWF, 50 analysts work to remove the images, tracking down the source and where they are hosted, working alongside the Crown Prosecution Services and British police forces.

Ms Hargreaves: "The year April died we removed 13,000 web pages from the internet - last year we took down 252,000 web pages.

"Every single web page we remove can have thousands of images - so that equates to millions of images of children being sexually abused."

Hywel Griffith reports on how the case unfolded

The IWF is one of very few organisations outside law enforcement globally, that is allowed to search for and remove these kinds of imagery.

Ms Hargreaves said online child abuse however "is at an all time high", with British police forces are recording more online child sex offences than ever and across more platforms.

"I have to face the fact that we will probably never eliminate online child sexually abuse, because it's a global issue," she said.

She added the IWF had seen a huge rise in this sort of crime in lockdown.

Prior to the pandemic there were 300,000 people classified as "representing a risk to children" in Britain.

In 2021, that figure rose to 850,000.

The charity said there were eight million attempts to access child sexual abuse images in Britain, across three internet service providers, in the first three weeks of the pandemic.

'Parents in the other room'

Victims online are getting younger and more vulnerable as predators no longer need to be in the room to abuse anymore, says the IWF

Ms Hargreaves said it is also more common now for young people be "tricked, encouraged and coerced" into filming the content themselves.

"These children are in their homes, their parents often think that they're safe because we can hear the sound of domestic chatter going on in the background, and yet the parents seem to be totally unaware that their children are being preyed upon by paedophiles", Ms Hargreaves said.

She added the images are often girls aged between 11 and 13 but said they are getting younger, and in the first six months of 2022, they removed 20,000 reports of self-generated content of children aged seven to 10.

"We have a national crisis around this, and we need to do everything we can to stop that," Ms Hargreaves said.

'Every photo is a crime scene'

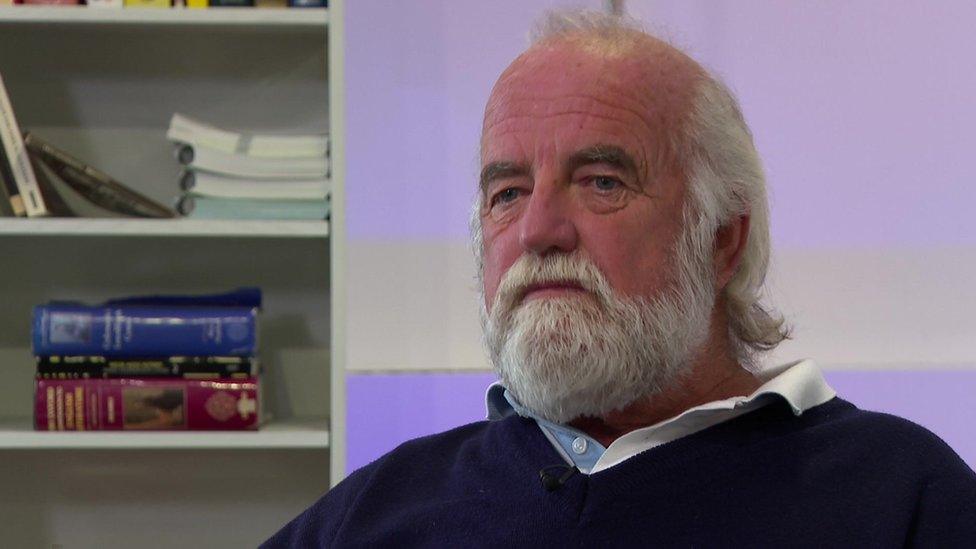

Dai Davies has worked on child abuse cases in the past and says more needs to be done to protect children online

Dai Davies, a former superintendent with the Metropolitan Police, assisted in the Madeleine McCann case but also consulted for April Jones'.

He said whilst changes were made at the time they did not go far enough and there needs to both "coordination" and "education" in order to tackle the issue.

"It was 10 years ago now and what was shocking was the discovery that the accused had so much child images on his computer. It was indicative even then of the issue of child pornography online," said Mr Davies.

He said it is particularly important now as more and more children are tricked into creating the imagery themselves.

"Each image is a crime scene and a crime against children and we have to as a society address it."

He added the crimes need to be prioritised and big companies held to account criminally if they are found to be negligent.

"Ten years on where are we? We are still dealing with this issue and the scale is horrendous."

He said a windfall tax on these companies might be a way to support police and organisations in protecting children.

David Cameron met with April Jones' parents in 2013 to discuss child abuse imagery online

The likes of Google and Microsoft have blocked thousands of search terms online, sometimes the searches are code words only known to perpetrators.

Claire Lilley, Google's child safety lead, said they were "deeply committed to protecting children and our users from harmful content" and take "an aggressive approach" to tackling and blocking child sexual abuse material.

She added they have "invested heavily in teams and technology" to removed material and help other companies do so, such as the IWF and The National Centre for Missing & Exploited Children in the US.

The UK government recently said the Online Safety Bill, external, which will require technology companies to protect users from child-abuse images, is due to return to Parliament.

It said: "The sexual abuse and exploitation of children online is an abhorrent crime. This government has a dedicated strategy to tackle it, backed by over £60m per year to pursue offenders, support victims and safeguard children.

"The Online Safety Bill will ensure tech companies are strictly obliged to remove any sexual abuse and grooming content to keep our children safe. Companies that do not step up will be held to account with fines of up to 10% of their global turnover."

- Published1 October 2022

- Published20 February 2022

- Published31 March 2021

- Published9 April 2015

- Published17 November 2014

- Published3 October 2019

- Published30 May 2013

- Published18 February 2016