Who do people in Wales think they are?

- Published

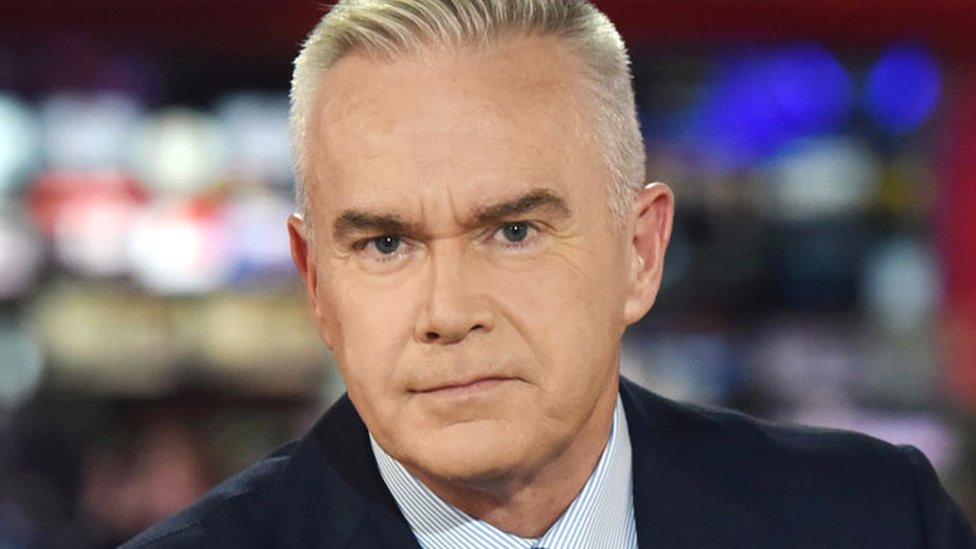

Huw Edwards takes stock of the decade since The Story of Wales was first broadcast

This is not a history lesson.

It is far too soon to write the history of the past decade in Wales. All I know is that the story of Wales has changed significantly in that time, and we are still trying to make sense of who we are and where we are going.

I am struck by the terms and quality of the debate about our future. We argue about things which should not even be matters of debate. We tend to avoid things which really do deserve attention.

Things we took for granted are suddenly questioned. Things we considered unthinkable are offered up as serious policy.

Being confidently, assertively, unapologetically Welsh is never - has never been, as we know - plain sailing. This fact of life can also be applied to that relatively new dimension of Welsh political activity, our devolved model of national government.

Until the pandemic struck, the possibilities of this model had not been fully explored. What happened is still being debated, but it brought a new focus - in Wales and beyond - on the way we are governed.

I had an interesting conversation with a former Secretary of State for Wales who relayed an exchange he had had with a senior cabinet minister about government spending.

The Welsh secretary was asking for a bigger share of the cake. "Who the hell do you think you are?" boomed the senior figure.

It is a very, very good question. Who do we think we are?

It is not a straightforward question, and if you ask people across Wales you will be rewarded with answers of all kinds.

So we took this deceptively simple question as the starting point for a journey around Wales this year.

Ten years after the history series The Story of Wales was first broadcast on BBC One in Wales - and later throughout the UK - we felt it was right to take stock and see how a turbulent decade had changed things.

The thing I enjoy doing most is talking to people. Asking them about their lives, their aspirations, their successes and disappointments.

I found myself full of respect and admiration for the way people try to make the most of their lives, and full of anger and resentment on behalf of those whose lives are blighted by a lack of fairness and justice.

The impact of second homes on all kinds of communities around Wales has hardly been out of the news, and I wanted to speak to people directly affected.

Gwynedd has the highest number of second homes in Wales

I met Dani Robertson in Rhosneigr who has struggled to find anywhere to rent within an hour's radius of her work.

She has been labelled a "troublemaker" after drawing attention to the huge rise in second homes and holiday lets in areas like Rhosneigr on the west coast of Anglesey.

She was keen to point out that with so many local people like her priced out of the housing market, tourist businesses and other employers were struggling to find staff.

Further south, on the Llŷn Peninsula, I met Jonathan Morrison. He has owned a second home in the tourist hot spot of Abersoch for many years but feels he's being pushed out of a place close to his heart.

A raft of different policies and plans has been floated during the past year, designed to tackle the housing market issues in places like Abersoch and Rhosneigr.

One particular policy has certainly made headlines - a 300% surcharge that councils can add to second homeowners' council tax bills.

It has not come into force yet, but Jonathan said it is the reason he sold his second home. Matters of fairness and discrimination run through this whole debate.

Jonathan, who is not opposed to all market intervention, feels policies like this discriminate against him. Dani on the other hand points to the fundamental injustice of being unable to afford a home in her own community.

The Welsh government has not needed any new powers to develop policies on second homes, but making changes on a bigger scale would be a different matter.

There is currently a constitutional commission taking evidence on people's preferences for the future governance of Wales - the Scottish government is in the UK Supreme Court arguing about the legality of holding a second independence referendum.

A commission is currently considering Wales' relationship with the rest of the UK

On a sunny day in July, I met Bria de la Mare in a pub in Wrexham. She was there to attend her first pro-independence rally and explained how her experiences of living near the border during the pandemic had changed her mind about an independent Wales.

A majority of Welsh voters clearly favours remaining in the union, but polls suggest an increase in support for independence, and Bria shares many of the characteristics of more recent converts to the cause.

She is young, she voted remain in the Brexit referendum and she is a Labour supporter.

In fact, polling suggests that half of all independence supporters voted for Labour at the last Senedd elections, though it is a party that firmly supports the union.

In the heart of the south Wales valleys in front of the striking Cyfarthfa Castle at Merthyr Tydfil I met historian Dr Darryl Leeworthy.

He painted a different picture of a unionism that typifies large parts of Wales. He argued that being independent wouldn't shelter us from any of the crises that are currently buffeting the country.

He also insisted that most people who are struggling with issues such as the cost-of-living crisis in places like Merthyr are not thinking about big political questions when their concerns are more immediate.

Voting in most kind of referenda and elections has consistently declined since a high point in the 1970s.

When I asked two different community workers in Merthyr where people thought power lay when it came to the big decisions that affect their lives, and where they expected to find help, the answers were consistent.

People look locally for assistance and decision making.

Those offering this view were at the heart of community projects to improve people's lives. Lee Davies is a community worker and independent councillor, and he helped establish the Gurnos Men's Project over a decade ago.

It is a multi award-winning volunteer scheme that helps unemployed and sometimes isolated men to make improvements to their own communities.

The shelf of trophies and certificates at their impressive community garden is proof of the project's impact. As well as improving the local environment it clearly makes a difference to the mental health and wellbeing of those who take part.

In the town centre, Heidi Jacobsen, who runs the Hope Pantry in the vestry of a beautiful church, is tackling a different problem.

Hope is an example of one of many "pantry" membership schemes that have sprung up in recent years and are sometimes confused with food banks.

They are a longer-term intervention where members pay a small weekly fee and have access to a range of produce that would often go to waste, and can choose as much fresh fruit and veg as they want.

Heidi pointed to the "squeezed middle", those with jobs but who struggle to meet the rising costs of energy and food.

The local community formed a strong part of people's identities here. It's where they looked to for support.

And centres of power like Westminster and Cardiff Bay seemed distant when dealing with issues as basic as feeding your family.

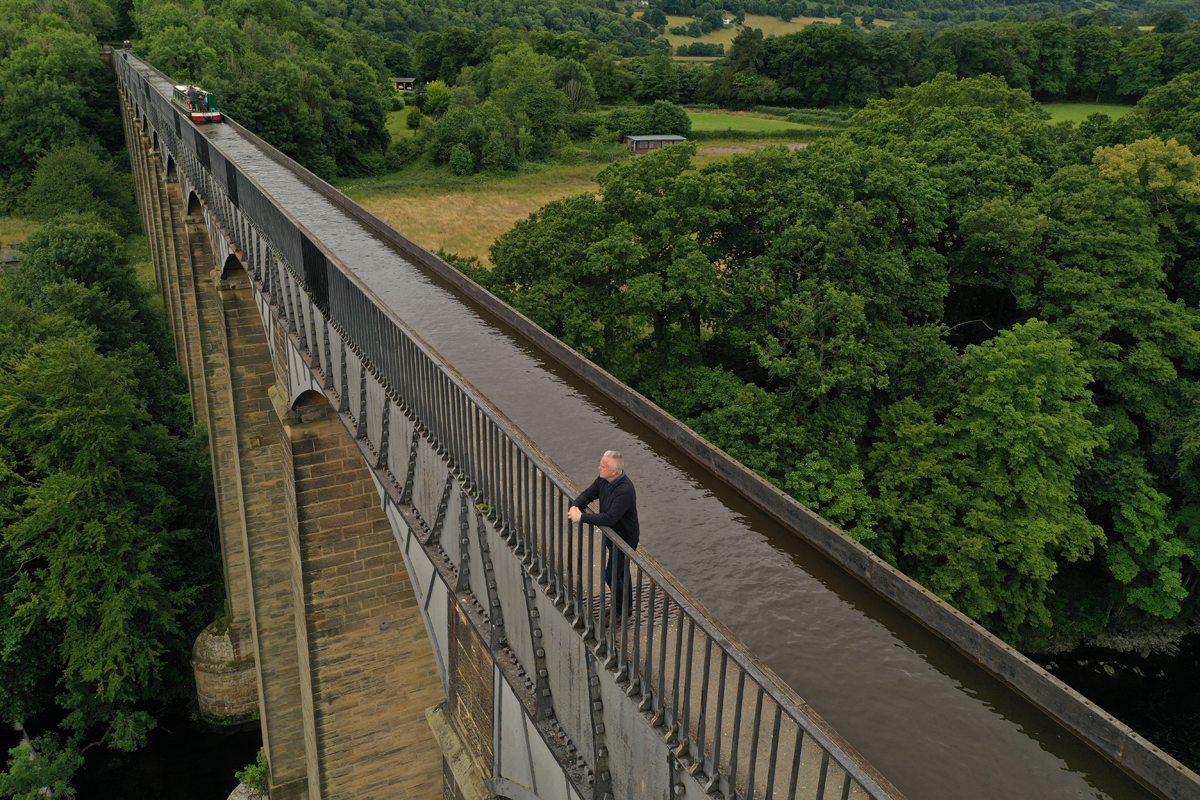

Huw at the World Heritage site, Pontcysyllte Aqueduct, a symbol of Wales' industrial past

Though I was exploring questions of national identity the interaction between local concerns and government policies was a regular theme.

Ian O'Connor, a tenant farmer in Carmarthenshire, pointed to the impact of Welsh government policies on rural communities.

He feared that a push for tree planting, though not a bad idea in itself, was helping corporations and investors buy huge areas of local farms.

He feared there was no guarantee his children would be able to have a future where they are being raised.

On the other hand, Gaynor Legall was hopeful about the introduction of a new Welsh curriculum where black history would be taught.

When talking about the development of the old Tiger Bay area of Cardiff her stark words were that the history of the area had been "totally erased." A new policy offered new hope.

This was also the message coming from Ameer Davies-Rana, who is passionate about Welsh government targets to achieve a million Welsh speakers by 2050.

Ameer was brought up in a household where Welsh, English and Urdu were spoken, but after leaving school he almost lost his ability to speak Welsh.

Now he is using his experiences as inspiration for a roadshow which tours schools all around the country to promote the one million goal.

In English schools it is all about sharing information and pointing out opportunities. When I met Ameer at a Welsh medium secondary, the message was a little different.

Here the focus was on overcoming the tendency of Welsh being just the language of the classroom.

He was sharing content from social media, offering tips on presenting video blogs and using his own story and sense of personal identity to enthuse and excite. It was very entertaining and the pupils responded well.

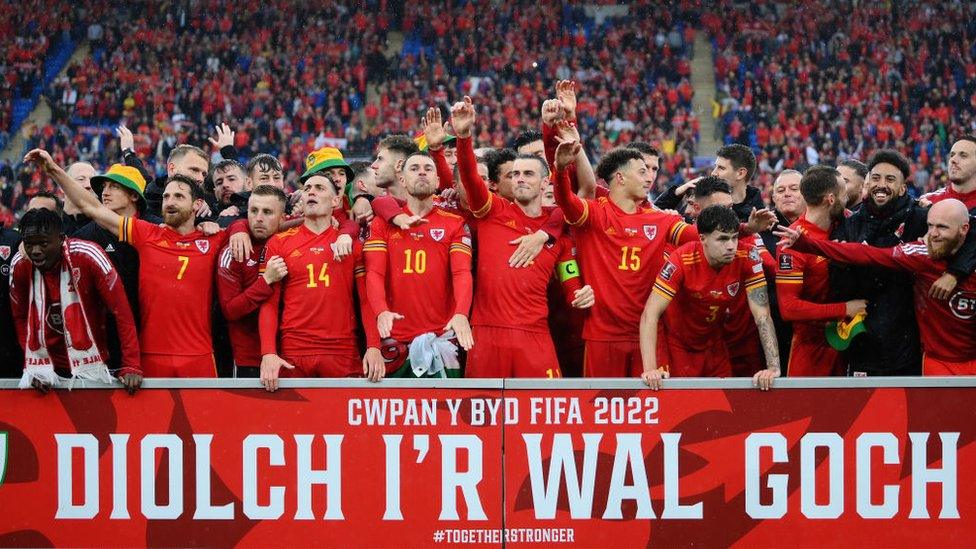

Sport and culture forms part of Wales' identity but a third element seems to have joined them

What did the tour of Wales teach me?

In all honesty, the journey was both uplifting and unsettling. It gave me hope and worried me at the same time.

But there was one binding thread. Many of the people I met pointed to decisions taken by the Welsh government when talking about their own sense of identity.

Culture and sport, I think it is safe to say, have been joined by a third dimension when it comes to the defining characteristics of Welsh identity.

It does not mean that you have to believe in a Welsh government to have a complete sense of Welshness.

Not at all. But the identification of Wales and Welshness has expanded beyond rugby, choirs, the Welsh language and castles. It now includes a political dimension, whether you support that model or not.

Polls suggest that much has changed since the Brexit referendum of 2016, including a rise in the number of people who describe themselves as Welsh only. But for me there's a different statistic that catches the eye.

The number of people wanting a weaker Senedd and government has fallen significantly, and, regardless of how they voted in 2016, a majority of Welsh voters oppose a reversal of devolution in a post-Brexit world.

That was my journey across Wales in the summer of 2022. A voyage of discovery, in every sense.

Wales: Who Do We Think We Are? With Huw Edwards is on BBC One Wales at 21:00 BST on Monday 17 October and afterwards will be available on iPlayer.

SIGNED, SEALED AND DELIVERED: Those who write, deliver and look forward to receiving letters

CURL UP WITH A GOOD BOOK: Aberystwyth book club members review their latest read

Related topics

- Published30 September 2022

- Published24 May 2022