Gaming: Video games 'help people with disabilities like me'

- Published

Some studies have found a link between computer games and mental wellbeing

"Video games are really important to me because with some things I can't always join in. But with video games, I can always join in with everyone."

Seth is 13 and uses a wheelchair due to a life-long progressive condition, so loves gaming because it helps him "experience things like other people".

He's one of the 44 million UK and three billion global gamers who play in the world's biggest entertainment industry.

But for Seth it is more than that: "Games are accessible to everyone."

Many parents worry that their child spends too much time playing video games.

Some studies have found a link between computer games and mental wellbeing, now organisations and those who work with young people say that, in moderation, gaming can help.

The children's hospice in south Wales where Seth receives care for his condition Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy, external has a games room where he can escape to a world of virtual reality.

"If you're in a wheelchair, you can't always run around with everyone so when I play Minecraft, I can run around and it's really fun," said Seth.

"I can join in with more stuff and people treat me as if I can join in more.

"It's an escape from reality where you let your imagination run wild. I love gaming because it just helps me experience things like other people."

Seth, the first wheelchair user to become a member of the Welsh Youth Parliament, started gaming during the first Covid lockdown in 2020 and enjoyed "building stuff and blowing up my brother's houses" in Minecraft.

The hospice where he receives care supports his love of gaming with a palliative care play specialist for young people with life-limiting conditions.

"I think gaming provides a level playing field, particularly for those who have barriers to access typical methods of play," said Heather Roberts of the Ty Hafan hospice, near Barry in Vale of Glamorgan.

"When they're in the gaming environment, all of their physical needs are removed and it means it's much more inclusive and accessible."

Martha said she was a shy teenager with low self-esteem and was bullied in school until she visited a community centre near her home and discovered she loved Minecraft.

Her self-belief started to flourish and mental health improved when Valleys Kids, external got her to help Welsh historical monuments organisation Cadw create a virtual reality model of the Welsh valleys.

"Gaming helped my confidence, 100%" said the 15-year-old.

"When the people we were working with would leave, we'd go on the Minecraft world and dig underground and create little houses under the ground," Martha recalled with a huge smile.

"That boosted my confidence because I had people to talk to and it was really fun, we bonded over that."

Martha helped Cadw create a Minecraft replica of the Welsh valleys where she lived

Martha now volunteers at Valleys Kids and helps support young people in some of Wales' poorest areas who may not have games consoles or digital devices at home.

She feels she learned more from educational gaming than traditional schoolwork as it was a "good way to advance motor, maths, English and history skills without it being boring".

"If you finish a sheet of maths homework, it's boring. But if you had to solve maths problems to get out of a maze, that's way more fun and you'd remember it more."

BBC Own It's top tips for safe gaming

Dylan also struggled as a teenager.

"I was bullied a lot in my childhood for being disabled and gay," he said. "It made me feel like an outcast, like I didn't fit in this world."

The turning point for him, he said, was gaming as it " helped me escape reality".

"Through gaming, it's allowed me to think about myself more and go 'it's OK to be the way I am and not allow anyone else to tell me any different'."

When Dylan was five, his disability was diagnosed by doctors.

"I have nearly everything under the sun. I've got ADHD, external, autism, external, ataxia, external, dyspraxia, external and I've got a rare condition called arsacs, external," said the 20-year-old from north Wales.

"And growing up I've been bullied about being gay so I went to gaming because it was a safe space for me, it allowed me to be in my own world and have fun."

Dylan was raised on Mario World, Just Dance, Call of Duty, Minecraft and Roblox and now, over a game of Nintendo Switch tennis, he told BBC Wales how gaming helped him become an actor and presenter.

Like many 13-year-olds, Seth enjoys playing video games

He now attends the Wicked Wales organisation for young film makers and has "produced my own show, I've had my own talent show, I've had a film done about my life and I've presented at festivals".

"Gaming has helped me have amazing opportunities."

Mental health charities have endorsed video games and gaming as being "really beneficial" for people's wellbeing.

"It's a place where people can build their own communities and can connect with new people," said Bethan Jones-Arthur of Mind Cymru.

"It's a place to relax and some games allow you to work on important life skills."

But experts warn gamers should find a "balance" between playing video games and time away from their screen.

"If you find yourself feeling irritable, tired, angry or frustrated, take a step back," added Ms Jones-Arthur.

"Make sure you're eating right, getting enough sleep and going outside if you can and do in some form of physical activity just so you're not constantly playing games."

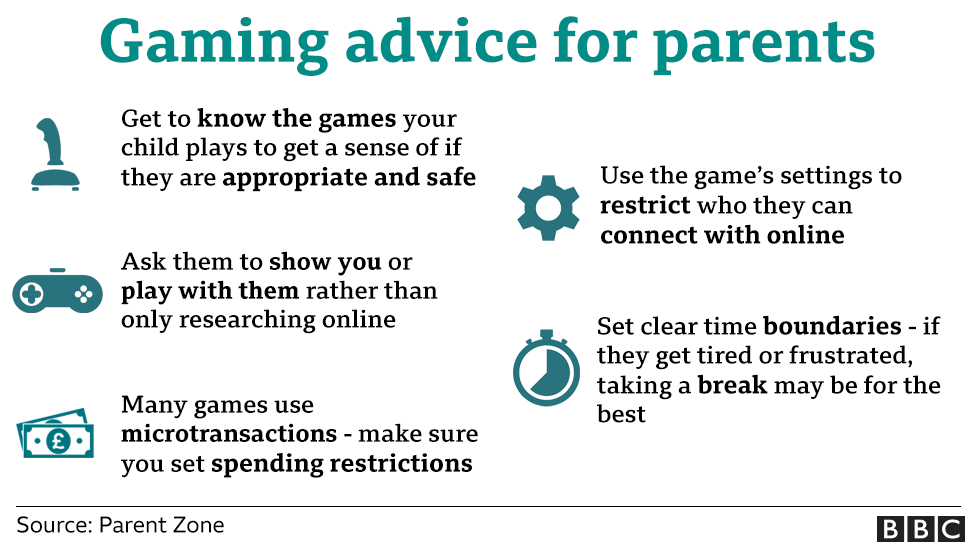

Mind also warned gamers against sharing personal information "even if they seem really friendly" while, Parent Zone, external, an organisation that helps families with digital advice, said there were risks that both parents and young people should understand.

"Understanding the games your child plays - and why - will help you have a better sense of if they are appropriate and safe," said Giles Milton.

"You could do your research online but the best way is often just to ask them to show you - or play with them."

If you have been affected by any of the issues in this story, the BBC Action Line has links to organisations which can offer support and advice

- Published13 October 2022

- Published27 July 2022

- Published31 March 2022

- Published14 November 2021