Gambling: Boy, 16, lost thousands after seeing advert

- Published

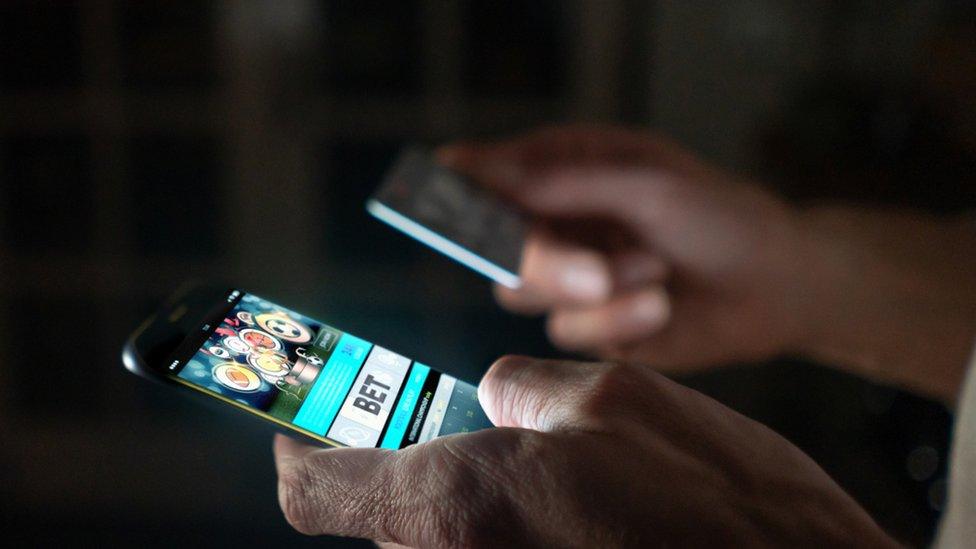

Emma says adverts online and on social media act as triggers for those with a gambling addiction

A 16-year-old boy lost thousands of pounds gambling in just a few weeks after seeing adverts at a football game, a support worker has said.

Nick Phillips, from Swansea, said the boy opened an account in his father's name an hour after a match.

Welsh MPs and anti-gambling charities are calling for the UK government to publish its gambling white paper, which had been expected before the summer.

The UK government said it was determined to reduce gambling harm.

Mr Phillips helps those struggling with gambling in Swansea, said the boy's family have stopped going to football matches because they want to avoid putting their son at risk.

He said: "This poor lad has gone home an hour after the match and opened an account in his dad's name after seeing the gambling ad."

Meanwhile, recovering gambling addict Emma, whose name has been changed to protect her identity, told Wales Live online gambling was "so dangerous" for young people, saying: "It's a real-life casino on your phone."

Nick Phillips has been called the "gambling guardian" of Swansea

She has signed up to an app that blocks gambling websites, but said there were still triggers on online games and social media.

A recent survey from the Gambling Commission found 31% of young people said they had spent their own money gambling in the past year, with 0.9% of children as young as 11 categorised as problem gamblers.

Carolyn Harris, MP for Swansea East, said legislation needed updating to keep up with technology.

She said: "If you think about the last Gambling Act in 2005, the first iPhone was invented in 2007, who could have foreseen how technology would come along in the way that it has.

"It's one of those hidden addictions that people don't want to talk about, and parents don't want to admit to."

Mr Phillips said another problem young people faced was loot boxes in computer games which can be bought to improve a gamer's performance, but the contents are unknown when the player pays for them.

He said: "It's the dopamine effect. They get a huge buzz out of it. These are children at the end of the day and they're vulnerable."

The UK government opted against regulating loot boxes in July, saying the prizes do not "normally have real-world monetary value outside of the game".

Loot boxes are unlikely to be included in the government's gambling paper and, while it said in July that they "may be linked to a variety of harms", including problem gambling, it sees "the ability to legitimately cash out rewards as an important distinction".

It added: "In particular, the prize does not normally have real world monetary value outside of the game."

Charles and Liz Ritchie set up the charity Gambling with Lives following the death of their son, Jack

Liz Ritchie, who founded Gambling with Lives with her husband after her 24-year-old son took his own life, said gambling was a "public health crisis".

She said: "The gambling industry is behaving like the tobacco industry, they have to create addiction in young people."

But Andy Robertson, a gaming expert, said parents could ensure their children were safe.

He said: "Every video game console has a parental or family settings area. One of the things I really like is the ability to say 'can this account make transactions? can it spend money? Also, how much can it spend?'

"So a nice thing to do is to sit down with a child and say, 'let's give you some pocket money each week , how much should that be?'

"Once you've set that limit, and they've spent the money in that time period, the child then can't make any more purchases without a pin number."

The BGC says games such as Penny slots are the most popular among children

The Betting and Gaming Council (BGC) said the most popular forms of betting by children were arcade games like penny pusher and claw grab machines, as well as bets between friends.

It added its members "take a zero-tolerance approach to betting by children and enforce strict age verification on all their products to prevent underage gaming.

"The regulated betting and gaming industry is determined to promote safer gaming, unlike the unsafe and growing online black market, which has none of the safeguards strictly employed by BGC members."

The UK government said it was determined to protect those most at risk of gambling-related harm, including young people and that ministers are working quickly to update legislation to make sure it is fit for the digital age.

Related topics

- Published11 February 2022

- Published15 October 2019

- Attribution

- Published14 June 2022

- Published21 November 2018