NHS Wales: Hospital staff 'in tears' over A&E pressures

- Published

Keith Royles lived over the road from the Ysbyty Glan Clwyd hospital

Patients being treated in chairs, staff in tears and an 18-hour wait for transfer from an ambulance.

These are some of the extreme pressures experienced by the Royal Glamorgan Hospital's emergency department.

Dr Amanda Farrow was called in early to a recent shift at the site serving much of the south Wales valleys because the nurse in charge felt it was "unsafe".

On arrival, the number of patients awaiting beds was far higher than trollies available.

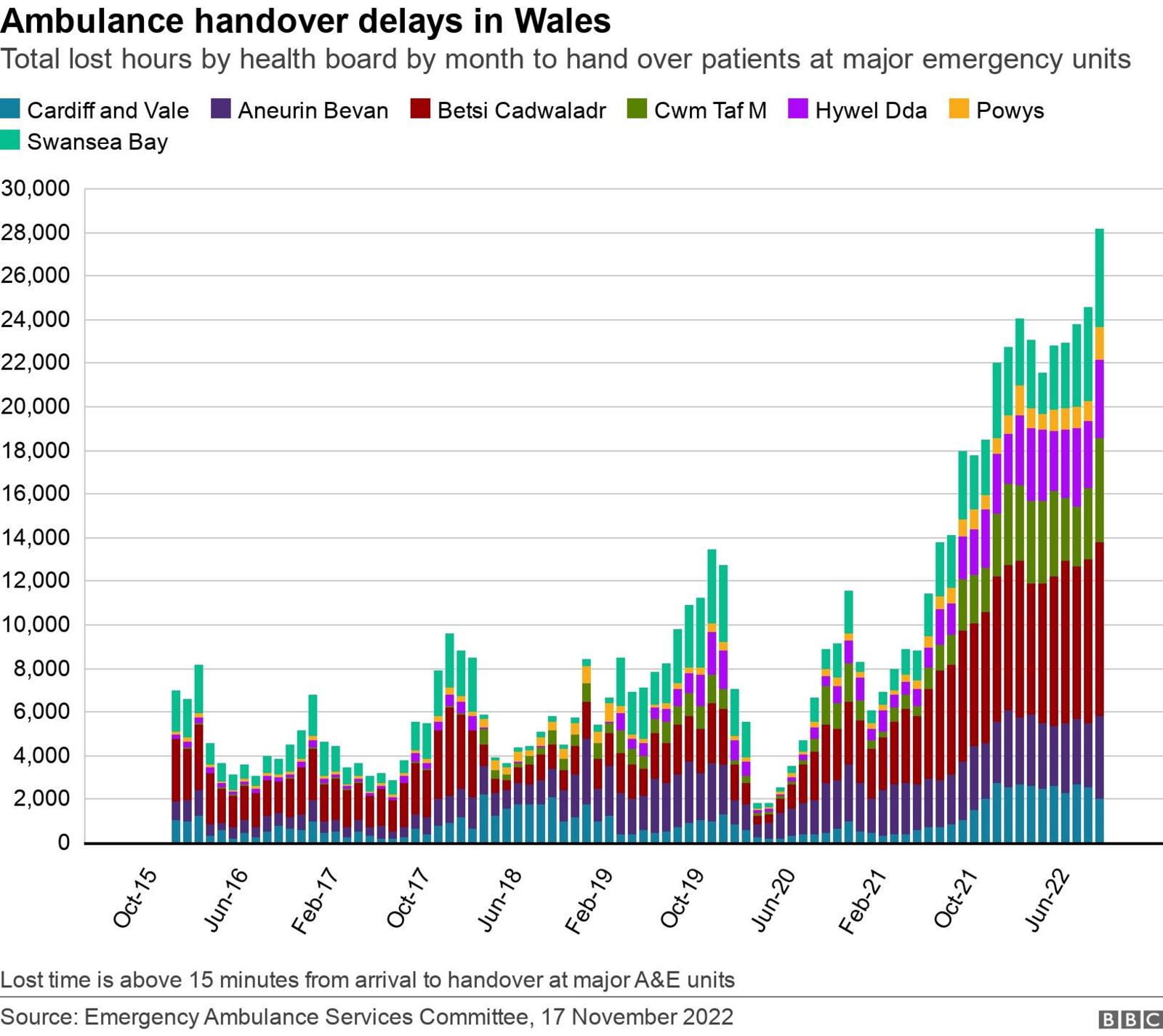

Meanwhile, six ambulances were queuing outside, unable to hand over their patients and, as a result, also unable to respond to other emergency calls.

Dr Farrow, the lead consultant at the A&E department of the hospital near Llantrisant, Rhondda Cynon Taf, said: "She has never rung me before so I know when I get that phone call that I just need to get up and come in.

"We have 16 trolleys and we had 28 patients waiting for beds in the morning. Our resuscitation room was full and we had some very, very sick patients that all arrived at a similar time.

"Patients who are not on trollies are obviously sat in chairs, which is not a good experience. We also have a finite number of chairs in the clinical space.

"A number of members of staff were in tears."

Dr Amanda Farrow says she has recently had to go into work early because the department was "unsafe" on low staff

The knock-on effect was soon felt outside the hospital's front door, with ambulances stacking up outside.

As a result the ambulance service was struggling to respond to urgent 999 calls in the community.

"In extreme cases the department can receive an immediate release request, calling on them to admit a patient and release the ambulance as soon as possible to attend an extremely urgent call," said Dr Farrow.

"Yesterday during my shift we had two calls for an immediate release, because there was an unwell baby and there was a lady in labour."

"[With] the first one we did manage to bring the patient in, with a view to getting one of our patients out, But the [call] later in the day we were unable to accommodate."

A&E department at full capacity leads to ambulance backlog

She continued: "It is a lot of responsibility for the staff - none of us wants to be making these decisions. We're all doing our best and there is concern around the impact this is having on staff because that does cause moral injury.

"It's not just patients arriving in the ambulance. The majority of our patients actually self-present to the hospital.

"We are having to pull them out of the boot of cars, they're coming by fire engine, with the police. We have to try and find somewhere to manage that and it's just a constant challenge."

'System is broken'

In September, Keith Royles, 85, broke his hip and was forced to wait seven hours for an ambulance, and then had to wait outside the hospital until the early hours of the morning.

His daughter Tina Royles told BBC Radio Wales Breakfast that her parents were "horrified".

"My parents put their whole lives into nursing and they're quite disgusted, they understand the pressures on the NHS staff, but the system is broken.

She said as a former police officer she knows how busy A&E gets, but it was never like it is now.

Despite the long wait, Ms Royles said the staff who looked after her dad were amazing.

Lee Brooks, executive director of operations at the Welsh Ambulance Service, said he was deeply sorry about Mr Royles' experience, describing the seven-hour wait as unacceptable.

"It will take a system-wide effort to resolve a system-wide issue and we continue to play our part to alleviate the pressure by treating more patients over the phone and at home and referring them to more appropriate areas of the NHS, negating the need for a trip to the emergency department."

Eleven ambulances were seen queuing up outside Royal Glamorgan Hospital on Thursday evening

Highest level of alert

Dr Farrow stressed that being "supportive to all of our staff" is extremely important to the department.

"We're a very close-knit team and we do try, at the end of the shift, [to] go around and chat to the staff just to make sure that everyone's OK," she said.

During the shift, the department was escalated to its highest level of alert - level 4/20 - meaning staff from across departments worked together to try to free up beds on the wards to ease the pressure in A&E.

This resulted in a decision to open dozens of beds as part of "surge capacity", including opening an unused ward. This in itself was difficult due to staff shortages.

There is also a dedicated team who try to identify patients, who, given the right care and support might be able to leave without being admitted.

Staff at Royal Glamorgan hospital are feeling the pressure of shortages

Gladly by the next morning the situation had stabilised.

"We had good supportive response from the rest of the sites... so this morning it's really quite pleasant which is a change but yesterday was extremely challenging."

But Dr Farrow said she worried about what lies ahead this winter as a result of staff shortages, the potential re-emergence of respiratory viruses like flu and the added demand of chronically ill patients who may have stayed away during Covid coming back into the system.

"It is quite scary to be honest.

"I think every winter in recent years has been challenging and I think we're fearful this is going to be even worse."

Related topics

- Published28 September 2022

- Published21 April 2022

- Published8 January 2021