Disabled actors patronised by TV industry, says artist

- Published

Ruth Fabby says actors with a visible disability are often restricted to playing stereotypes

Actors with disabilities are too often cast in roles to make non-disabled people who control the creative industries look good, an artist says.

Ruth Fabby said actors with a visible disability were often restricted to playing stereotypes.

She said those with hidden disabilities were being excluded in favour of those with a more obvious disability.

"I have had friends who have been told they don't look blind enough to play a blind part," she said.

"Other people have said 'we want someone with learning difficulties but we want them to have Down's because that's more obvious'."

Ruth stepped back from her paid role at Disability Arts Cymru because of a lung condition

'We should have disabled Romeos'

Performer and playwright Ruth, who has worn a hearing aid since she was six and has a lung condition, was director of Disability Arts Cymru before she left the role in December and is on the Arts Council of Wales.

"Often our presence is to make non-disabled people look better because they're helping us - it sounds lovely but it's a patronisation," said Ruth, who was born in Liverpool and lives in Dolgarrog, Conwy.

"Why can't we just be seen as normal everyday people, which is what we are.

"We should have disabled Romeos - it is about making being disabled ordinary."

Chris Tally Evans has decided against "battering down the walls of the media" and mostly works on his own projects or within community and disability arts

'It's bruising'

Chris Tally Evans, a writer, musician and artist from Rhayader, Powys, shares Ruth's frustrations.

"There's a certain sort of disabled person who makes us all go 'ooh, look at them, they're being really inclusive and right on because they've got a wheelchair user, or an amputee or somebody using a blade'," he said.

"If you have what is ostensibly, as far as TV is concerned, a hidden impairment, then perhaps you wouldn't have been included.

"Even when people are ostensibly trying to do the right thing I question their agenda.

"I wonder who's it for? Is it actually for disabled people or is it to make the companies look good?"

Chris, who began losing his sight in his late 20s, said he was once offered the role of a blind man only to have it revoked over health and safety concerns before being asked to coach a non-disabled actor to play the same role.

"I was furious," he said.

He has decided against "battering down the walls of the media" and mostly works on his own projects or within community and disability arts.

"It's bruising and it's too hard," he said.

Cara Readle wants decision-makers the industry to engage more with disabled actors

'Really frustrating'

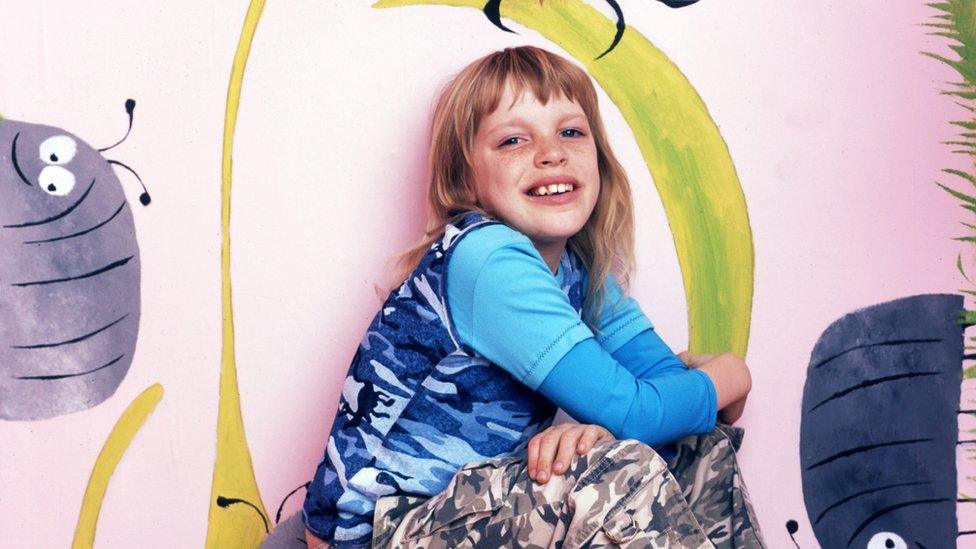

Actor Cara Readle's big break in the industry came when she was cast as Layla Jones in BBC's The Story of Tracy Beaker when she was 12.

"I was very lucky, so I had no idea how hard this industry was going to be," said Cara, now 32, who has cerebral palsy.

She said these days most of her time is spent trying to get auditions.

Cara Readle played Layla Jones in BBC's The Story of Tracy Beaker when she was 12

"Since I've left uni it's been a real struggle to kind of keep myself busy and when you email so many people and apply for so many parts it can be disheartening but you do also have to keep positive, you have to keep going," she said.

Cara, who lives in Llanelli, Carmarthenshire, thinks casting directors sometimes waste her time so they can say they have at least auditioned disabled actors.

"I've been to a lot of auditions, gone all the way to London, done my best audition and I've come out knowing they're not going to cast a disabled actor as I just got that vibe, you kind of get that feeling off them even though everyone's been lovely to me in the room," she said.

"You just know you're there so they can say 'yes, we saw disabled actors for the part' with no real intention of casting them in the end."

Cara says she has never met a disabled casting director

She wants decision makers the industry to engage more with disabled actors.

"If they just have a couple of meetings with a couple of disabled people, they don't have to be actors, but just to talk normally about what our needs would be.

"It's opening that conversation with able-bodied people in the industry," she said.

Better still would be having more decision-makers with disabilities, she said.

"I've never come across a disabled casting director," she said.

"There needs to be more disabled casting directors, producers, people within the industry that can speak out, make the industry more inclusive and the work they produce more inclusive."

She is also frustrated by casting directors' reluctance to cast her for non-disabled roles.

"TV programmes and films are meant to represent real life and in real life we don't get to choose who has a disability, we don't get to choose who's born with cerebral palsy so why in casting can they choose that this particular character can't have a disability," she said.

"It's not true to life, it's not real and it's really frustrating that we can't just be seen for any role."

Ruth said that when roles are written for performers with a disability they are often stereotypical disabled characters with "shallow narratives".

"Every bond villain is always disabled in some way - they still play to that stereotype, that we're nasty and horrible or need help and support," she added.

She said another trope was that the person with a disability is "inspirational".

"I hate that narrative, we just want to live our lives and we shouldn't be inspirational paralympians to be accepted," she said.

Chris wants an end to disabled actors being asked to do unpaid work

What needs to change?

Chris said he won't be happy until disabled people making up their representative numbers through every tier of an operation, including in senior roles.

He would also like to see an end to people with disabilities being asked to do something for nothing, external, such as disability awareness training for non-disabled people and taking part in focus groups "where everybody else in the room is getting paid for it".

Despite the issues, Ruth said overall she was feeling hopeful.

"There are some brilliant initiatives that are coming through, and I have helped shape some over the years," she said.

"I've seen the changes happening very quickly in the last five years."

Ruth believes reverse mentoring, when someone mentors a person more senior than them, is a useful tool in helping people understand barriers that "people inadvertently put up, that unconscious bias".

She would also like to see access riders, external for everyone in a cast rather than just those with disabilities, and that productions needed to be aware they may be able to access financial help to support disabled employees from Access to Work, external.

She said work being done on access passports, external could be a "gamechanger".

"It can be simple as saying not 'how can I help you?' but 'what do you want me to do to help you?' so you put an emphasis back on the person having the right to say what they need," she said.

"You're either disabled or you're not disabled yet - let's all accept it as part of our humanity and if we do that we'll start to see big changes happening."

What are broadcasters doing about it?

BBC Wales approached eight of the largest broadcasters who represent about 90% of UK broadcasters' employees - Bauer, the BBC, Channel 4, Global, ITV, Paramount (which includes Channel 5), S4C and STV.

All who responded agreed there was under representation of disabled talent on our screens.

S4C said it would be participating in the Creative Diversity Network's Diamond project, external to capture reliable data on the representation of disabled people and other under-represented groups on its productions. It said it had several projects for broadcast that provide "a voice to disabled talent".

ITV said it was tacking the issue through initiatives such as its disabled writers in development initiative Step Up 60, external, specific leadership programmes internally, and staff were given mandatory disability inclusion training. It said it was also collaborating with other broadcasters through the TV Access Project (TAP), external.

Bauer Media Audio UK said it was having ongoing discussions with a number of external partners to assist it in areas of disability and neurodiversity. It said it was developing new ways to use data, training and awareness to ensure a positive work experience for all.

The BBC said it had made commitments to help remove barriers, create better workplaces and increase authentic and meaningful portrayal in its programmes. It said its three year commitment to invest £112m into diverse content was the biggest financial investment in on-air inclusion in the industry. It said the BBC Elevate scheme has been progressing the careers of mid-level deaf, disabled and neurodivergent talent and supports 30 placements within production companies.

Channel 5 said it supported initiatives across the industry and would continue to build on-screen representation in a sensitive and organic way. "Our dramas, in particular, will feature acting newcomers as well as off-screen talent," it said.

STV said it worked in partnership with an internal peer group focused on access. It said through its STV Expert Voices initiative, external its news and current affairs team trains individuals from under-represented groups and over 700 had been trained so far. It is also part of TAP.

Channel 4 said it was committed to improving disability representation and that it had among the highest percentages of disabled staff in the UK media at 11%. It said it wanted to increase this to with 12% by the end of 2023. The broadcaster said it had helped set industry standards for working with disabled people and that it would continue to challenge itself.

- Published23 August 2021

- Published1 July 2020

- Published8 October 2021