Tryweryn: The man who bombed a dam to save a village

- Published

Owain Williams was sentenced to one year in prison for blowing up an electricity pylon at the Tryweryn site in 1963

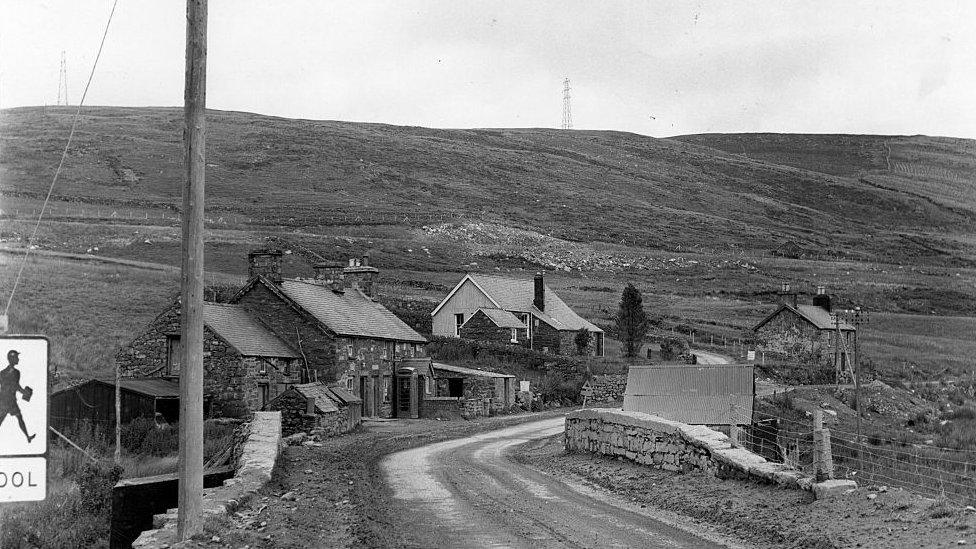

In the summer of 1955 the people of Capel Celyn, a rural, Welsh-speaking village in north Wales, learnt their home had been earmarked as the site of a new reservoir to provide drinking water for Liverpool.

This would mean every house in the village near Bala, Gwynedd, being destroyed and all the residents being forced to move elsewhere.

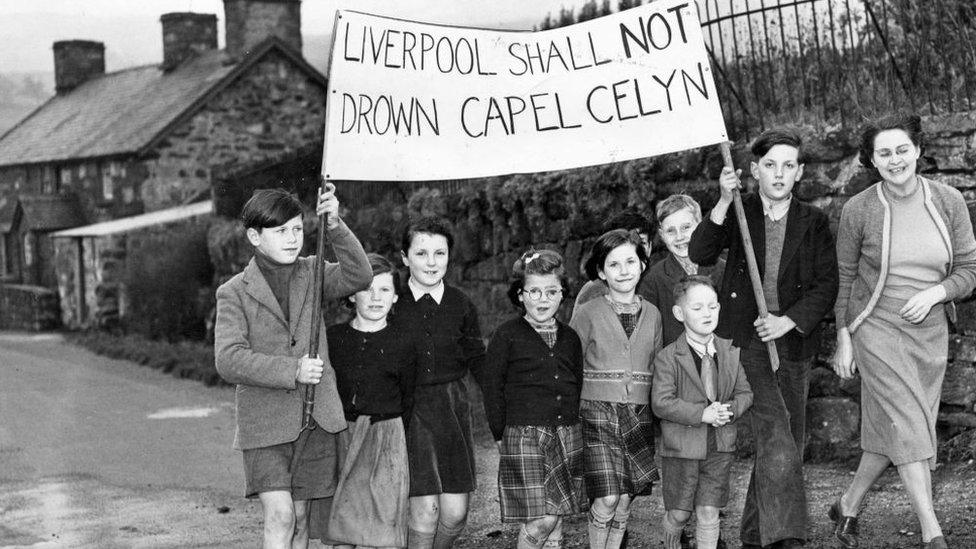

For nine years after the announcement, the villagers fought to save their homes, with protests and marches through the streets of Liverpool.

With the future of the village looking bleak, three men decided to take matters into their own hands.

"It was something that needed to be done and it didn't seem anyone else was going to do it so it was left to us to do it," said Owain Williams, who features in the BBC Wales' podcast Drowned, which will be released next month.

"Do you sit back at home watching telly, or do you go out in the snow and do something for your country?

"We decided to do that."

While the dam was still under construction in early 1963, farmer's son Mr Williams, Aberystwyth student Emyr Llewelyn, former RAF military policeman John Albert Jones formed Mudiad Amddiffyn Cymru - the Movement for the Defence of Wales.

On the night of 9 February 1963, they travelled through blizzard conditions to plant a 5lb (2.3kg) bomb which destroyed an electricity transformer on the site at 03:15 the following morning.

Welsh nationalist demonstrators were confronted by police on 21 October 1965 at the opening of Tryweryn reservoir

'We didn't set out to be glorified'

Emyr Llewelyn was later sentenced to 12 months in prison for the attack.

On the day of Llewelyn's conviction, Williams and Jones blew up a pylon at Gellilydan near Trawsfynydd in Gwynedd.

They were both caught and Williams was given a one-year prison sentence while Jones received three years on probation.

The village could not be saved - two years later Capel Celyn was flooded, forcing 70 people to leave their homes.

Its 12 houses, school, chapel and post office disappeared under water.

The phrase 'Cofiwch Dryweryn' - seen here in Milford Haven - has become associated with Welsh nationalism and independence movements

The story of the drowning of Capel Celyn fuelled the nationalist cause, with 'Cofiwch Dryweryn' ('Remember Tryweryn') graffiti popping up across Wales.

'Cofiwch Dryweryn' hoodies and other merchandise are worn by some in Wales as a symbol of Welsh national pride.

To some, Williams is a criminal who risked lives. To others, he is seen as a freedom fighter and a hero.

"We didn't set out to be glorified," said Mr Williams.

Schoolchildren from Capel Celyn protesting against the drowning on 18 December 1956

"At the beginning, we got lots of criticism from people and lots of nasty things were said to us, not so much to our faces but behind our backs certainly, and we had to handle that.

"It's not easy to go to prison. It's not a choice."

When asked why he chose violence and actions that endangered lives, he said: "I'm not happy with the use of the term violence because violence was being used against people in Capel Celyn."

He said for the villagers, losing their homes, school, chapel, and having their relatives' remains moved from the graveyard was hugely traumatic.

Tryweryn reservoir today

"Some of them died of actual broken hearts, but no-one talks about that," he said.

"The only regret I have is [it was] affecting my own family, because I had little children at the time and eventually my marriage broke up which caused suffering for my children.

"They were insulted at school, shouting things [like] 'your father is a blah blah blah' and that's not nice at any time, of course. Maybe I have regrets in that direction."

Hugh Roberts says there were concerns he would be attacked for giving evidence in court

'I was here at the wrong time'

Hugh Roberts found himself giving evidence in court after stumbling across the bombers on the evening the bomb was planted that would go on to destroy an electricity transformer.

Speaking from the layby where he first saw them near Cwmtirmynach, he said: "I'd stopped here because I couldn't go any further because of the snow."

He said he saw another car get stuck in the snow so went to help.

"There were three young men in the car, saying they were going for the A5 to London," he said.

"I helped them get the car free from the snow, pushed the bonnet, and on they went."

The next day, when he heard about the bombing he thought it was possible they were involved, and was visited by police after telling his boss of his concerns.

A couple at their home in Capel Celyn on 27 February 1957

"The policemen came to pick me up from Cerrigydrudion, four police officers, they were worried people would attack me, they got letters threatening me," he said.

Looking back, he wishes he had never been involved.

"I wish I hadn't had seen them, but I didn't have a choice. I was here at the wrong time," he said.

Elwyn Edwards said there were mixed reactions to the bombings

'You long for what was once here'

Elwyn Edwards grew up in the nearby village of Fron-Goch and his family farmed in Capel Celyn.

He took part in protests against the planned reservoir.

Standing beside it, he is able to point out where his grandfather's house and the village school once stood.

"It's like you can see through the water to my childhood. The road went up here towards the old village," he said, pointing.

"You get used to it, but you long for what was once here I suppose."

He said when the drowning of the village was announced some local people were in support.

"[They] thought it would bring work here," he said.

"Others were against it because they were drowning the farms and the water was going for free.

"Very mixed, it was, and still [is] today."

Mr Jones Parry, the postmaster, outside his post office at Capel Celyn on 10 December 1956 which was submerged when the valley was flooded

He also remembers mixed reaction to the bombings.

"Some were for it, others against it," he said.

"Wales hadn't woken up to its identity back then. It still hasn't but it's better now."

He believes the drowning of Capel Celyn changed the course of Welsh history.

"It's had a lasting effect on our nation," he said.

"I don't think we would have had the Senedd if it wasn't for the drowning of the village. This was the awakening."

Dr Nia Wyn Jones says the drowning of Capel Celyn "crystallised the fact that Wales was politically powerless"

'A response to that powerlessness'

Dr Nia Wyn Jones, a lecturer in History at Bangor University, said the flooding of Capel Celyn was "a terribly important moment" for the nationalist cause.

"The fact that Tryweryn happened against the wishes of a large section of public opinion in Wales crystallised the fact that Wales was politically powerless," she said.

She described the bombing as "a response to that powerlessness through direct action, illegal action".

"This was something that had been advocated in Welsh nationalist circles before but maybe had not captured the public imagination in the same way."

She said it had been "politically complicated" for Plaid Cymru, with it having to demonstrate a "principled opposition to violence" alongside "support of the Welsh cause".

She said Bala Town Council had not opposed the scheme in the same way that Plaid Cymru and the county council did, and over time opposition to Tryweryn "faded away and became less popular".

Capel Celyn in July 1963

She believes the bombing "crystallised fears" for the UK government that unless more concessions were offered to Wales in terms of the language and self governance, there was a "threat of further violence and of losing electoral dominance in Wales".

She said in wider Welsh society "not everyone was talking about Tryweryn in the '50s and '60s".

"There were bigger things on a lot of people's plates," she said.

She believes since devolution there had been "more of a willingness to consider the complexities in the Tryweryn narrative".

"There's more of a self confidence in Wales to look critically at our history... Welsh political powerlessness, the disappearance of the language, maybe they don't feel quite as existential now."

BBC Wales' podcast Drowned: The flooding of a village launches on BBC Sounds on 1 March

WHO DO WE THINK WE ARE?: Huw Edwards explores the source of Wales' identity

DABBERS AT THE READY: A glimpse into life at a Tonypandy bingo hall

- Published21 October 2015

- Published21 October 2015