Stained glass breathes new life into derelict buildings

- Published

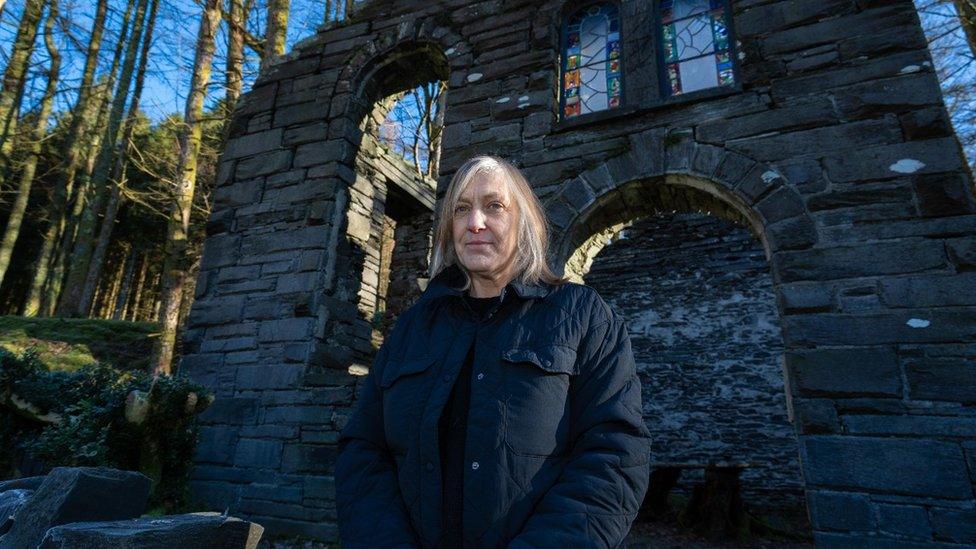

The artist says she has always been drawn to Wales' derelict buildings

For the past three years Christina Dembinska has been breathing new life into forgotten buildings with her handmade stained glass window installations.

The history behind lonely, abandoned structures fuels her passion for giving them a second chance and wowing passers-by.

Christina, 63, started the guerrilla art project while studying for an MA in Glass in 2020, before turning her focus to where best to display her masterpieces.

''I loved making stained glass windows, but where was I going to put them?" she said.

''And then I had this idea of fitting them into derelict buildings. I was really curious about the history behind them.''

Christina Dembinska says her artwork captures her curiosity about derelict buildings she comes across

Christina, who lives and works in London, has always been captivated by Wales. Her grandmother was originally from Monmouth and her grandfather from Holyhead on Anglesey.

"As soon as I arrive and I see the hills, something happens,'' she said.

''In Wales there are a lot of derelict structures, and I am drawn to wondering who lived there and what went on there.''

The first of her installations were fitted in two old farm buildings on the border of the Hafod Estate in Ceredigion.

Christina hopes her work will bring attention to forgotten properties across the country

She hopes her work can go some way to helping preserve historical buildings.

''It's only a small thing, a stained glass window. But maybe having it there somehow sparks it back into life,'' she said.

''It's such a beautiful medium. As soon as the light comes through, it just sings.''

''By bringing attention to the building, it could spark someone's curiosity and maybe they will then look into the history of that site.''

Research is important to her creative process, wanting to ensure the window is relevant to its location.

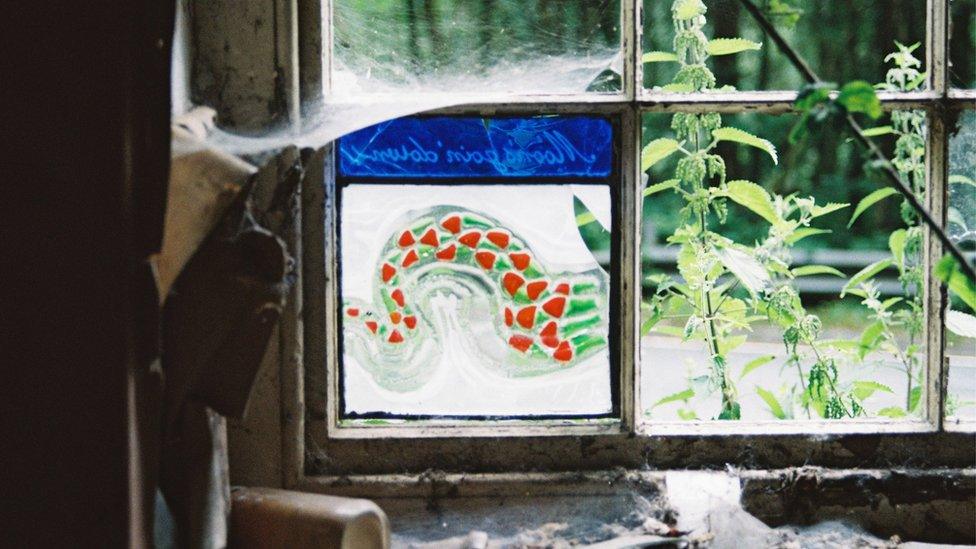

''I often put song lyrics or words into them. I can engrave things into the glass that is related to the community or that tells a story of the building.''

Christina's choice to install her art in remote locations means her work goes unnoticed by many people

Most of her glass artwork is placed in remote locations and in structures varying from crumbling quarries to deserted farm buildings.

It means some of her art could go unnoticed by most, but Christina believes that's part of the magic.

''I like hearing that someone has come across one of the windows by chance. The more remote they are you do start to wonder whether anybody will see them'' she said.

''But I think, interestingly, people do. You don't realise how many people are wandering around in remote places.''

Some of the windows have been damaged or destroyed after being installed

Sadly, as was the case with her installation at Dinorwic Quarry, near Llanberis, Gwynedd, some of her pieces do end up broken or destroyed.

''The first time it happened I was a bit upset,'' she said. ''But then I thought, actually, when it's there you can't protect it anymore. It's almost become part of the project.

''There is something about the fragility of it. The glass is like the building, both can be broken.''

Christina's work has helped her form relationships with people from local communities

However, the majority of her work has been received positively.

In some cases she has even formed connections with people from the local communities.

''Once, I wrote a letter to a man who owned one of the buildings I'd put a window into. He actually wrote back and shared the history of it with me.

''He'd inherited the place from his grandfather, who was a miner, and they used to farm the land together.

''He couldn't come and see it any more because he's elderly and it was on top of a very steep hill, but it brought back all these memories for him.

''A lot of things have happened like that which have been really lovely, a consequence of the art.''

Some of Christina's installations have since been broken or destroyed

One of her larger installations was at the ruins of a chapel, built in the 1870s, in a slate valley near Machynlleth, Powys.

After coming across the building, she wandered over to one of the few neighbouring houses.

The couple who lived there, Sarah Samson and Steve Watkins, told her about the work they had done clearing the chapel for its 150th anniversary and their hopes of restoring it.

They helped Christina fit the windows, eager to bring it back into the community.

Sarah said: ''There is so much heritage in Wales. It needs everybody to look at it and ask what are we going to do with it that is relevant?'

''Work like Christina's says somebody cares, somebody wants this place to be noticed.''

Since the clearing of the chapel, the people of the valley now come together once a year to celebrate Christmas there.

Sarah Samson and Steve Watkins at the chapel near Machynlleth

Dr Mark Baker is an architectural historian from Conwy who has also founded the Gwrych Castle Preservation Trust, which in 2018 bought the Grade I-listed Gwrych Castle, near Abergele, Conwy.

''It was a desire, on my part, to give something back to my community by trying to restore somewhere,'' he said.

''We've had I'm a Celebrity at the castle now and it's been featured all over the world. All of this brings people to north Wales and the local area.''

He said Welsh government involvement should go further to preserve historical buildings.

''There's a whole raft of properties that are at risk and I think there should be a review of how these are protected.

''In Wales, the system doesn't always work because lots of the local authorities push culture and conservation down the agenda due to funding.

''So, historic buildings and their preservation are often the first things that get cut.''

For Christina, art is more than just something pretty to look at

The Welsh government said it recognises the "positive action communities can take to protect and preserve what matters to them".

''This activity is supported by Cadw through its capital grant programme and the grant aid it gives to organisations, such as the Architectural Heritage Fund."

Christina believes art is one way communities can help save historical structures in Wales.

''I think one of the functions of art is to make you think or draw attention to something and look at things in a different way.

''That can be enough to spark your curiosity and think about these buildings.''

For more on this story watch Wales Live on iPlayer

- Published28 September 2022

- Published12 November 2022

- Published24 November 2020

- Published28 July 2021