Titanic: Amateur radio heard SOS in Welsh town 3,000 miles away

- Published

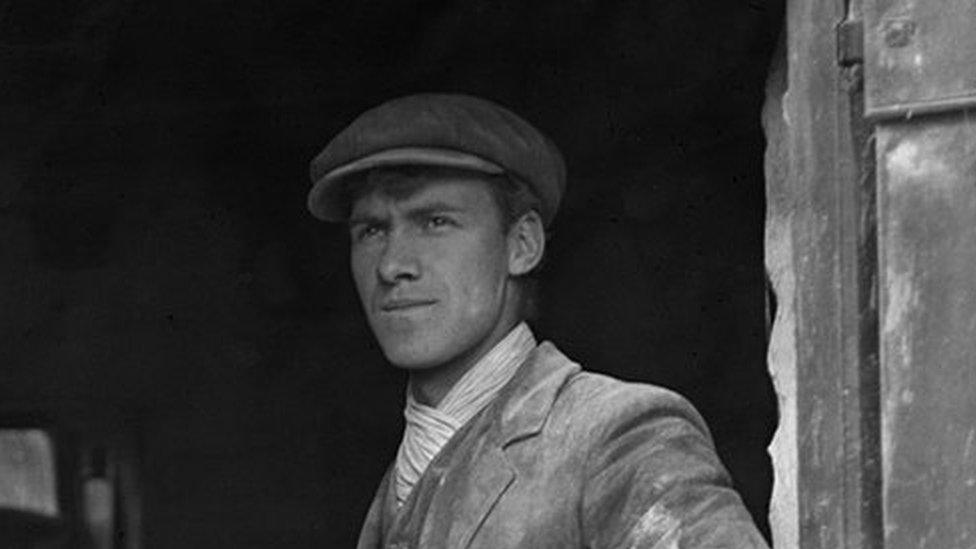

Artie Moore was looked at as "oddball" but picked up the distress signals of the Titanic from thousands of miles away

When the Titanic hit an iceberg while crossing the Atlantic in 1912, its telegraphers desperately sent out distress calls hoping somebody, somewhere might hear them.

But among the first to respond was an amateur radio operator some 3,000 miles (4,800km) away in south Wales.

Self-taught Arthur Moore received the signal at his homemade station in Blackwood, Caerphilly county.

He rushed to the local police station, but was met with incredulity.

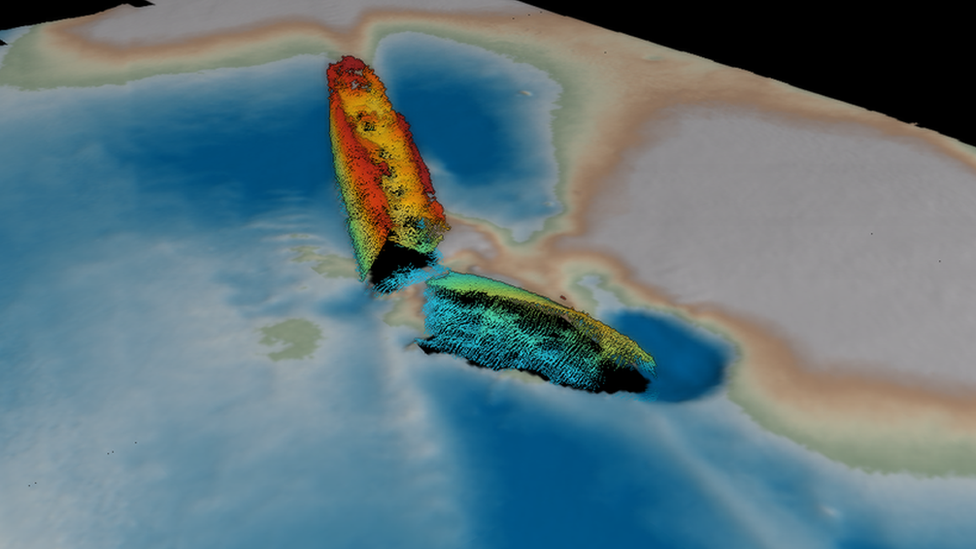

The first full-size digital scan of the famous shipwreck was recently revealed, enabling it to be seen without water for the first time.

And while the radio enthusiast could do nothing to help those on board the Titanic, he went on to pioneer an early form of sonar technology which helped discover its resting place decades later.

"Artie", as he was known to locals, had already hit the headlines for his radio equipment a year before the Titanic sank.

In 1911, he had intercepted the Italian government's declaration of war on Libya - a feat which saw him featured on the front page of British tabloid newspaper the Daily Sketch.

Born in 1887, Artie and his brother took over the running of a mill from their father and were entrepreneurs and pioneers.

Before there was electricity in the area, Artie Moore used the waterwheel to charge local farmers' batteries

Lyn Pask, chair of Blackwood's history society, said the brothers owned "some of the earliest motorcars in the Gwent region", developed machines for local farmers, and gave the area its "first access to electricity through charging batteries from the generator they'd created, powered by the mill's waterwheel".

But Artie's love of engineering had come about through a tragedy, after he lost a leg in an accident at the mill as a youngster.

This only inspired him to his first invention, a counterbalance on his bicycle which allowed him to ride by pushing down with his one good foot.

His scale model of a steam locomotive from the lathe at the mill won a magazine competition.

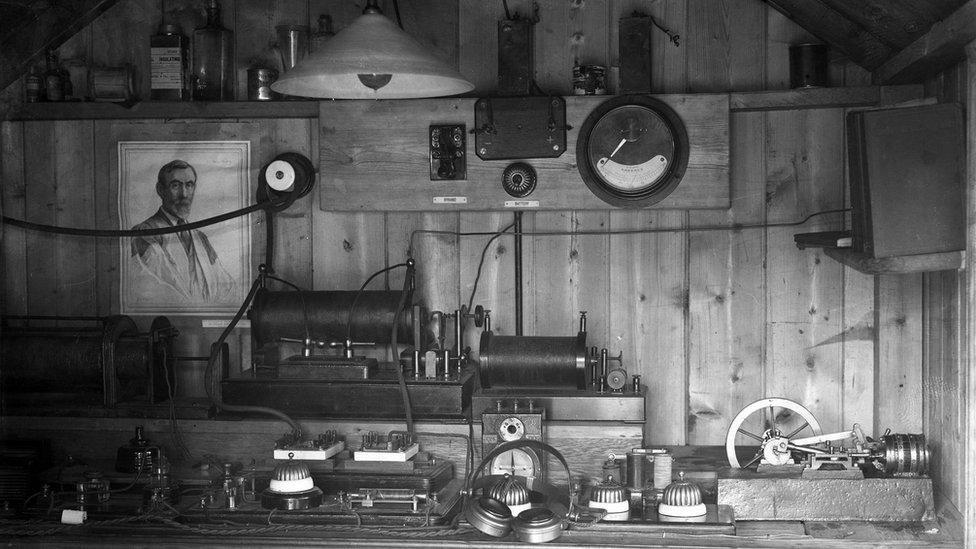

His prize was a book called Modern Views of Magnetism and Electricity which sparked his interest in radio telegraphy.

Amateur radio enthusiast Billy Crofts, who now lives in London but originally hails from Llantrisant, said that at the time Artie was looked at as something of an oddball.

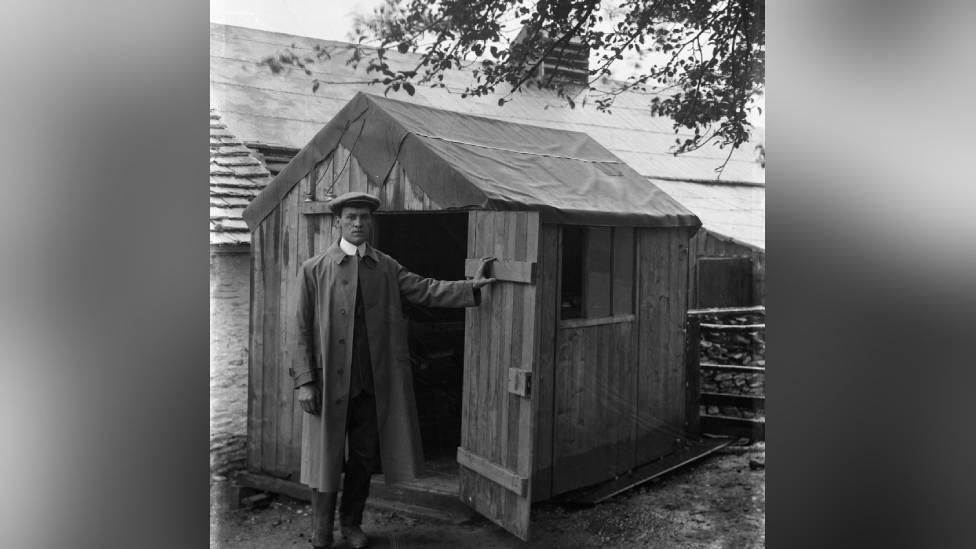

"He strung up all these aerials made from thin strands of copper wire from the Gelligroes mill, over the nearby River Sirhowy and slung between trees up the hillside to an old barn," Mr Crofts said.

As a result, he explained, Artie could receive radio messages from further away than anyone had managed or even thought possible before.

More than 1,500 people died when the Titanic sank in 1912

"People thought he was off his head, and that believing he could intercept signals through bits of wire was something akin to paranormal psychology."

That was certainly the reaction of the Caerphilly police, when in the early hours of 15 April 1912, Artie pedalled to the station to report the Titanic's SOS calls.

"Righty-ho," they are said to have mocked him. "We'll take a look. Just you get yourself back to bed now, and don't bother yourself any more."

Though Mr Pask said that outside south Wales, Artie was taken very seriously indeed.

"Soon enough, newspaper reports came through and they corroborated every single detail of what Artie had told the police, even down to the Titanic's use of the recently adopted SOS distress signal," he said.

"In Blackwood it might have been thought of as black magic, but to those who knew and understood, wireless telegraphy was the internet of its day."

Artie Moore was also well known for intercepting the Italian government's declaration of war on Libya in September 1911

Mr Pask said Artie's "brilliance" was soon noticed by some "highly important people".

Among them was Guglielmo Marconi, a radio telegraphy inventor.

He had originally predicted that radio signals could pass 2,000 miles (3,200km), but Artie had received them over 3,000 miles (4,800km) off.

Within a year, Marconi had signed up the amateur to his wireless company.

As Marconi's apprentice, he designed the first communications which could reach between Britain and the Falkland Islands during World War One.

In World War Two, he pioneered an early form of sonar - a technique that uses sound to navigate, measure distances and communicate with objects in water. This helped to guide Allied ships around German U-boats in the North Atlantic.

Artie Moore began his radio work from a shed in his garden, but soon moved on to bigger things

Artie retired to Jamaica in 1947, but shortly after developed leukaemia and returned to Bristol for treatment, where he died a year later.

In 1985, 73 years after his amateur radio picked up the passenger liner's calls for help, it was the sonar technology he pioneered that was used in discovering its final resting place on the Atlantic seabed.

Related topics

- Published13 May 2022

- Published12 June 2022

- Published27 September 2022