Parkinson's disease: New research could reveal early causes

- Published

Researchers are listening in to the "conversations" between brain cells to find out why some of them die

Listening to the "conversations" of brain cells as they develop could help researchers to better understand the early causes of Parkinson's disease.

Parkinson's, external is the second most common neurodegenerative condition after Alzheimer's disease.

The disease causes parts of the brain to become progressively damaged over many years.

But relatively little is known about its early stages, as much of the damage happens before symptoms appear.

Now a Cardiff University team is using cutting-edge techniques to help understand the disease's earliest causes.

By taking cells "back in time", the researchers hope their findings could aid the search for new treatments.

"The journey of Parkinson's, we think, is quite a long one," said Dr Dayne Beccano-Kelly, who leads the research.

"We might see symptoms at later stages of life, on average at around 65 years old... but we know cells in the brain that are very important for movement and cognition stop working at much earlier stages.

"We also have about 60-80% loss by the time people come into clinic, but we know that doesn't happen overnight.

"So there's a window of time before cells begin to die in which we may be able to help."

The Cardiff University researchers say there is a window of time before brain cells begin to die

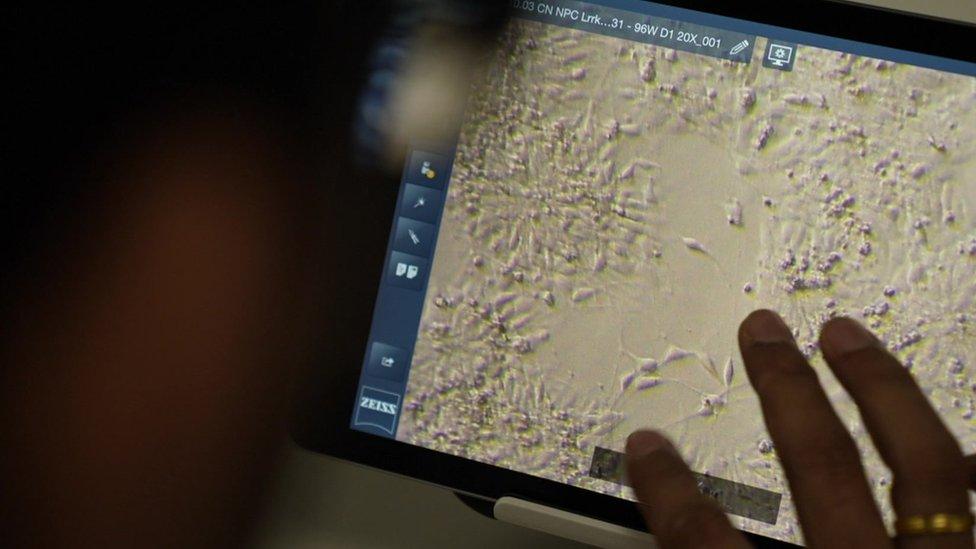

The researchers are collecting skin cell samples from people with Parkinson's and also from individuals who do not have the condition.

The team then "reverse-age" those cells - in other words, drive them back in time so that they revert to become stem cells.

They then use various methods to encourage these cells to develop into neurons, which are brain cells.

At various stages of the journey, the team try to tap in to the electrical communication happening between the cells using hi-tech equipment.

"The idea is we're trying to listen in to the cross-talk or the communication between neurons in the brain... a bit like a secret agent listening in to a conversation between two people," explained Dr Beccano-Kelly.

By looking at the differences that occur over time in the Parkinson's cells versus the non-Parkinson's cells, the team hopes to better understand the variety of factors that contribute to the condition.

This includes the inability of certain brain cells to clean-up waste proteins inside them, which could result in the cells dying.

"It's a bit like how a car engine might break down on your way to a conference or a flight.

"There's a number different things that contribute to exactly how the car breaks down and understanding what those are and when they're occurring can help us pinpoint where we might be able to intervene."

The team have been awarded a grant of over £320,000 by Parkinson's UK to carry out their research.

Parkinson's is the fastest growing neurological condition in the world.

In Wales, there are proportionately more people living with the disease than in any other part of the UK.

Prof Julie Williams, director of the UK Dementia Research Institute in Cardiff, said the research was "pushing the boundaries".

"By understanding the mechanisms we can test for novel drugs - drugs that are out there used for other purposes - which could come into the clinic quickly."

'I'm still me, in my head'

Ken Howard, 76, from Cardiff, was told he had Parkinson's a decade ago.

He described being given a blunt message from the consultant who diagnosed him.

"He said: 'There's no cure, it's progressive, it's degenerative which means you're just going to get worse. The best you can do is take the medicine you've been prescribed and you might get two and a half or perhaps three good years'," said Ken.

"Now I don't know about you, but I don't like being told that something is out of my hands and I thought there and then 'I'll get more than three good years' and that was 10 years ago. So I've proved him wrong."

Ken has recently taken part in a skydive, abseiled from a 10 story building and flown in a Spitfire

Ken said frequent exercise and setting himself physical challenges - such as skydiving and abseiling - had helped to mitigate the progression of the disease.

"You've got to set yourself new challenges, because apathy is an ally of Parkinson's," said Ken.

But Ken's condition has nevertheless had an effect. He has lost 4 and half stone (28kg) and has a visible hand tremor. His body can sometime jerk violently or freeze completely - especially in stressful situations.

"The annoying thing is, like all people with Parkinson's, I'm still me in my head. I'm still Ken Howard that loved playing rugby, a bit of a know-it-all and cheeky chappy.

"Now I've got this grumpy face which isn't me at all. But the worst thing is you know who you are and what you used to do and haven't changed your personality in any way. But your body has become disconnected from you."

Although not a direct participant in the Cardiff University study, Ken has taken part in a number of other research projects which he said were vital in giving people hope.

"You are told time is limited, you are told it's going to get worse and that there's no cure. So people give up hope and surrender to it.

"But I'm going to give Parkinson's a good run for its money. It's the fastest growing neurological condition in the world... and that's why research like this is absolutely vital."

Related topics

- Published3 November 2022

- Published7 September 2022

- Published24 April 2023

- Published17 September 2019