The Hay Poisoner: Was Herbert Armstrong wrongly hanged?

- Published

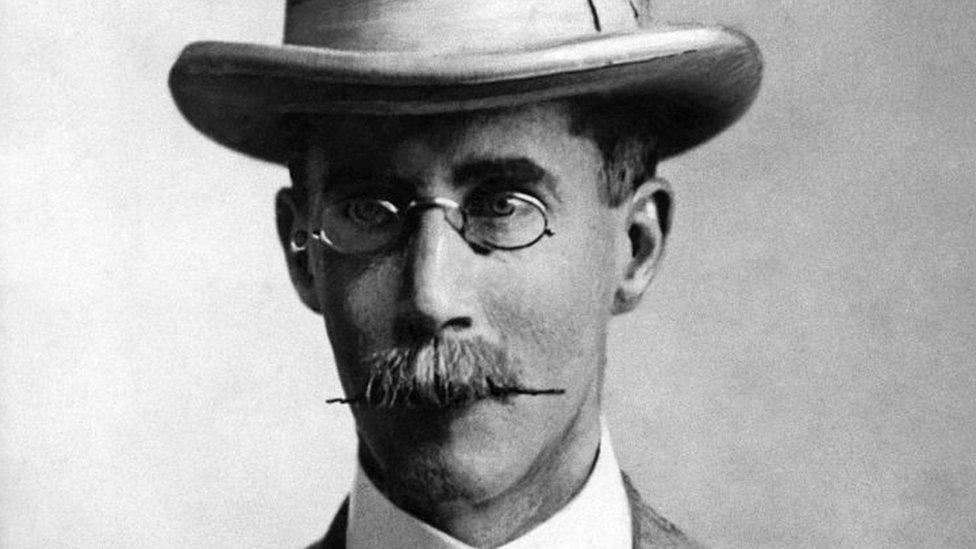

Major Herbert Armstrong has been described as a pompous little man with a waxed moustache

Fresh doubt has been cast on a 100-year-old murder conviction that saw a solicitor sent to the gallows for poisoning his wife with arsenic.

On 22 February 1921, Kitty Armstrong died at their home in Hay-on-Wye, Powys, from supposed gastritis, heart disease and inflammation of the kidneys.

But just months later, her husband, Major Herbert Armstrong, was accused of poisoning a rival solicitor, which led to his wife's body being exhumed and a murder trial that gripped the nation.

In his new podcast, US journalist Joe Nocera and a host of experts conclude it was a miscarriage of justice.

The case of "the dandelion poisoner", as Armstrong was referred to by the papers of the day, has all the ingredients of a classic Agatha Christie novel and has been intriguing armchair detectives for more than a century.

Stephen Bates, author of The Poisonous Solicitor, describes Armstrong as a pompous little man with a waxed moustache and spectacles, proud of his station who insisted on being called by his military title, despite never being in active combat.

Kitty, meanwhile, is described as a woman with a reputation for being highly strung, reserved and bossy.

In February 1921, Kitty came down with a severe case of diarrhoea, she could not hold down food, or get up and down the stairs without assistance.

She died early on 22 February.

No-one suspected Armstrong had a hand in her death until eight months later, when he invited rival local solicitor Oswald Martin to his home, where they shared scones and tea.

Maj Herbert Armstrong, who always maintained his innocence, was sent to the gallows in 1922

After returning home Oswald became unwell. His father-in-law Fred Davies, a chemist, questioned if he had been poisoned.

When he said he had dined with Armstrong, the chemist told him Armstrong had bought arsenic from him weeks before his wife died. This planted the seed and Oswald became convinced Armstrong was trying to kill him.

A doctor took a urine sample from Oswald which was sent to Scotland Yard. Months later the results came back: Oswald had arsenic in his system.

Police arrived at Armstrong's office on 31 January 1922 and discovered a twist of arsenic in his pocket, which he told police he used to control dandelions in his garden. He was charged with attempted murder.

His arrest prompted questions about his wife's death and nine months after she had been buried her body was exhumed for testing. She was found to be riddled with arsenic, and Armstrong was promptly charged with murder.

But why would he want his wife dead?

Investigators found three affectionate letters in his bureau from a widow in her 40s. They met during the war when Armstrong was stationed near her home in Bournemouth. They also found condoms at his home.

During his trial, Armstrong's doctor would tell the court he had treated him for syphilis, implying he had strayed from his wife.

Then detectives discovered Kitty's will, which months before her death had been changed to exclude her family and leave everything to her husband.

Had he killed his wife so he could live off her money with his lover?

Until his dying day, Armstrong never stopped insisting he had not poisoned his wife and was innocent of her murder. But the jury did not believe him and on 31 May 1922 he was sent to the gallows.

Major Armstrong arriving at court in 1922

That seemed to be the end of the story, but in 1975 a book was written about the case. Exhumation of A Murder by Robert O'Dell raised questions about the fairness of Armstrong's trial.

Then 20 years after that came another: Dead Not Buried, later renamed The Hay Poisoner. It was by Martin Beales, who was a solicitor in Hay-on-Wye, like Armstrong.

He died 12 years ago.

More than that, he worked in Armstrong's old office and even went on to buy his house Mayfield, now known as The Mantles.

His law firm had represented Armstrong during his trial and kept hold of all the documents, which he devoured along with the transcript of the trial.

"He got sort of a bit obsessed about it," his wife Morwenna told the podcast.

With the blessing of Armstrong's only surviving daughter Margaret, Beales spent years working on his book and became convinced there had been a miscarriage of justice.

Last year another book was published which again raised questions over the conviction: Stephen Bates's The Poisonous Solicitor.

Rival local solicitor Oswald Martin and his wife arriving at the trial in 1922

Podcast Agatha Christie & the Dandelion Poisoner, external is the latest attempt to uncover the truth.

But what is it about this case that continues to suggest there has been a miscarriage of justice?

The case was based on circumstantial evidence - no-one actually witnessed Armstrong putting arsenic in food or even being unkind to his wife. Then there are a doubts over the forensics.

Celebrated pathologist Bernard Spilsbury, external told the court the arsenic present in Kitty's intestines showed a large dose was taken within 24 hours before her death, when she would not have been mobile enough to get out of bed.

But forensic toxicologist Prof Atholl Johnston told the podcast he could not possibly have known that.

"We can't line up a lot of volunteers and give them arsenic or give them drugs and see what happens to them... for him to say she couldn't have taken it three of four days before, I think it's impossible for him to say because he doesn't know, it is his opinion," he said.

Podcast host Joe Nocera believes the judge, Justice Darling, who was due to retire following the case, wanted to leave on a high with a conviction, so did not conduct a fair trial.

In his closing remarks, he spoke for four hours, leaving the jury with the words: "She died of arsenical poisoning undoubtedly... if she did not die of suicide but died of a dose of arsenical poisoning administered at some short time before her death who had the arsenic? Only the defendant."

Author Stephen Bates told the podcast: "There was a degree of unscrupulousness which I found quite extraordinary."

Caroline Crampton, host of the Shedunnit podcast added: "I think the trial was riddled with problems, whether you think he did it or not."

Then there is the defence case to consider - that Kitty killed herself.

Armstrong's barrister Sir Henry Curtis-Bennett told the court Kitty had spoken about potential suicide and knew where the arsenic was kept.

A nurse testified Kitty had asked her if a person throwing themselves through an attic window would be sufficient to kill someone. A friend told the jury sharp objects had been removed from the house to keep Kitty safe.

Notes taken during her six-month stay at an asylum suggest she was suffering delusions about not caring for her children or paying her servants correctly and was in poor physical health. She left that institution one month before her death.

While she was there, Armstrong would frequently make the 120-mile round trip to visit his wife - is this the actions of a man plotting her death?

While there are those who believe the trial was unfair, does anyone who has studied the case believe Armstrong was innocent?

"There's a possibility, and I know this is maybe a radical theory, but maybe he really did know she'd taken her own life and maybe the reason he never brought it up was because of all the shame surrounding it," suggested podcast producer Poppy Damon.

Law professor Sir John Baker had another suggestion: "Could it have been an assisted suicide?"

Stephen Bates said while researching his book he believed he was probably innocent until he came across something intriguing - another alleged poisoning by Armstrong.

He said he was told a former tax inspector suspected Armstrong had tried to kill him.

US journalist Joe Nocera believes Armstrong was an innocent man

Ten months after Kitty's death, the tax inspector had sent Armstrong a letter saying he owed back taxes.

He was invited to join Armstrong for dinner, on the drive home smoked a cigarette Armstrong had given him, and became violently ill.

The next day the tax inspector bumped into his doctor who commented on how unwell he looked and noticed a distinctive smell on his breath - arsenic.

"If you ask me now I think he was probably guilty," said the author.

Historian Jeremy Black, Sir John Baker and former police officer Tony Price all told the podcast they believe Armstrong killed his wife but he would not be convicted on the evidence presented in court if he had been on trial today.

But Joe Nocera remains convinced Armstrong was an innocent man.

"Kitty hadn't just thought about suicide, she'd talked about it out loud," he said.

"When you think about the kind of person he was, the evidence that he did truly love his wife, the effort he made when she was in the asylum, that he really did use arsenic as a weed killer, that she was depressed and talking often about suicide - it make you think 'yes, she had arsenic in her body because she killed herself'."

Related topics

- Published23 July 2023

- Published29 March 2019

- Published30 October 2022