Abergele train disaster victims given online obituaries

- Published

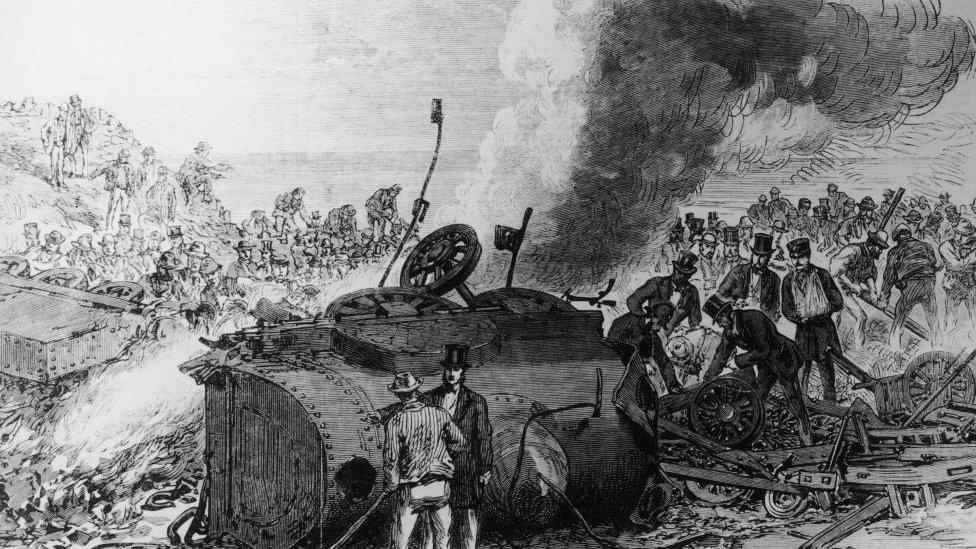

The scene of the 1868 Abergele Train Disaster, sketched by an onlooker shortly after it happened

The 1868 Abergele train disaster was the worst British railway catastrophe of its day.

Its 33 passengers were killed when six wagons carrying paraffin careered into the path of an oncoming express train.

Called "The Lockerbie of its time," its victims - all too badly burnt to be identified - were buried in a nearby communal grave.

But now they are remembered in a series of online obituaries for the first time.

The terrible incident involved a London and North Western Railways (LNWR) express train dubbed 'The Irish Mail', which had been heading from Euston to Holyhead before being bound for Dublin by ferry.

And the tragic fate which befell it could have been so easily avoided, said Rhodri Clark, founder of HistoryPoints.

The non-profit organisation has installed more than 2,200 QR codes at points of historic interest across Wales.

"If they'd only known then what we take for granted now," he said, explaining how several factors contributed to the disaster.

These included the transport of flammable liquids on open goods wagons, insufficient signalling and warning on the line, the use of wooden carriages and - perhaps most incredulously by modern safety standards - doors which were locked from the outside to prevent passengers falling out during transit.

"The Irish Mail - which comprised of a locomotive, a guard's van, three first class carriages, a mobile post and sorting office, four second class carriages and a rear brake van - was running late for a ferry to Ireland that afternoon on August 20, 1868," he added.

"There was a slow-moving goods train ahead of them on the line, which was ordered to shunt into a siding to allow the Irish Mail to pass by.

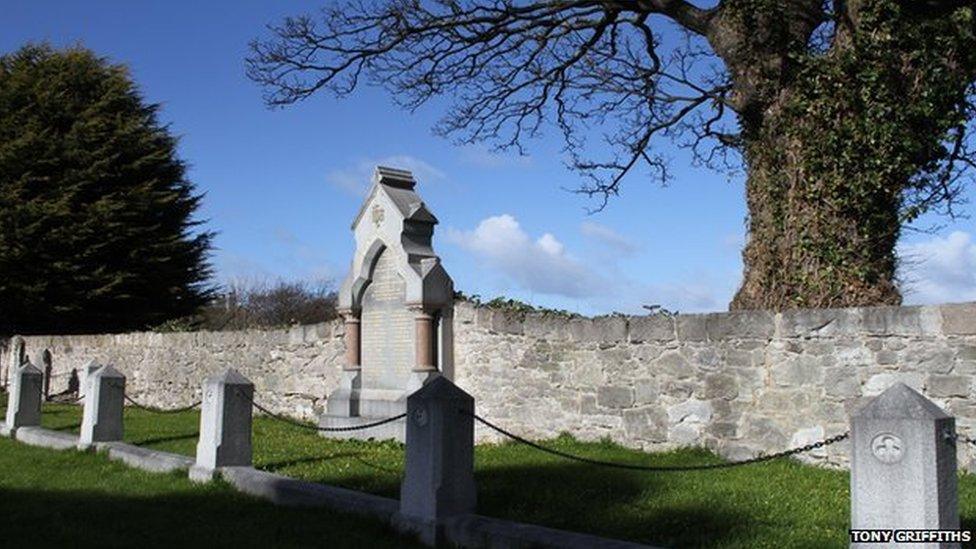

A memorial to the rail crash victims is at St Michael's Church, Abergele

"However, the siding wasn't long enough to accommodate all 43 wagons of the goods train, so the Llanddulas station master ordered that it be split up so it could fit into the sidings on either side of the line."

But, in the ensuing chaos, a brakeman failed to apply the brakes to six of the uncoupled wagons.

These were then shunted roughly by the rest of the train and began freewheeling downhill and into the path of the Irish Mail.

The ensuing fireball instantly claimed the lives of 33 people onboard, their injuries so bad as to make individual burials impossible.

Unable to prove who was who, they were laid to rest in a mass grave behind St Michael's Church in Abergele.

Nevertheless, thanks to in-depth research by Dr Hazel Pierce, a member of the Association of Genealogists and Researchers in Archives, each person's story can now be accessed by scanning a QR code on their shared memorial at the site.

Scars left on rescuers were profound

She likened the incident to the subsequent Lockerbie terrorist disaster in 1988 because, while the majority of the dead came from elsewhere, the event itself had a lasting effect on the locals who valiantly tried to come to their aid.

"I believe there was only one Welsh victim aboard the train, but the scars it left on the quarrymen who came to the rescue were profound," said Dr Pierce.

"One eyewitness described the sight and smell of the burning train, while locals formed bucket chains over 200 yards from the sea to provide water to fight the inferno.

"Throughout it all they must have knowing they were fighting a losing battle too - the fire was so intense that even the coins in the post office carriage had fused together in the heat of the blaze."

A quirk of fate saw all 33 of the fatalities occur in the foremost three first class carriages, meaning most of the victims were wealthy.

Thereby, their lives were later celebrated in the newspapers.

This was not so of the others which included three railway workers, a little girl, and various servants.

"As a genealogist the easiest part of this job was finding out about the land-owners, industrialists, politicians and aristocrats," added Dr Pierce.

"But far more rewarding was giving a voice to the women and less-recognised people who perished."

Amongst those Dr Pierce described was Will Smith, the Irish Mail's guard, whose wife had given birth to their eighth child just a week before.

Also featured was 22-year-old William Henry Owen - an organist and choirmaster of St Bartholomew's Church in Dublin - whose composer father John Owen had popularised Hen Wlad Fy Nhadau as the Welsh national anthem.

Also included was the youngest victim, 10-year-old Louisa Symes, who was travelling to Ireland with her guardian, Judge Walter Berwick.

Dr Pierce was similarly drawn to the disparity in the amounts of compensation awarded from LNWR to the bereaved families via the courts.

"Whilst the landed Edwards family were granted £52K for their loss of potential earnings, the grieving brother of Lord Farnham's valet, Edward Outen, was only given £75 for the loss of his possessions," she added.

"Meanwhile, Outen's widowed mother, for whom he was a carer, was awarded £225 in maintenance to help keep her until her death years later."

You can read all 33 obituaries by visiting the HistoryPoints website, external.

- Published4 August 2012

- Published20 June 2023