Salmon: Why this fisherman refuses to keep his catch

- Published

Weirs such as this one are among barriers threatening several species in the area

A fisherman says he no longer keeps any of the fish he catches as he strives to repopulate rivers.

Experts have warned native salmon are on the brink of extinction in Wales, despite surviving in the area for thousands of years.

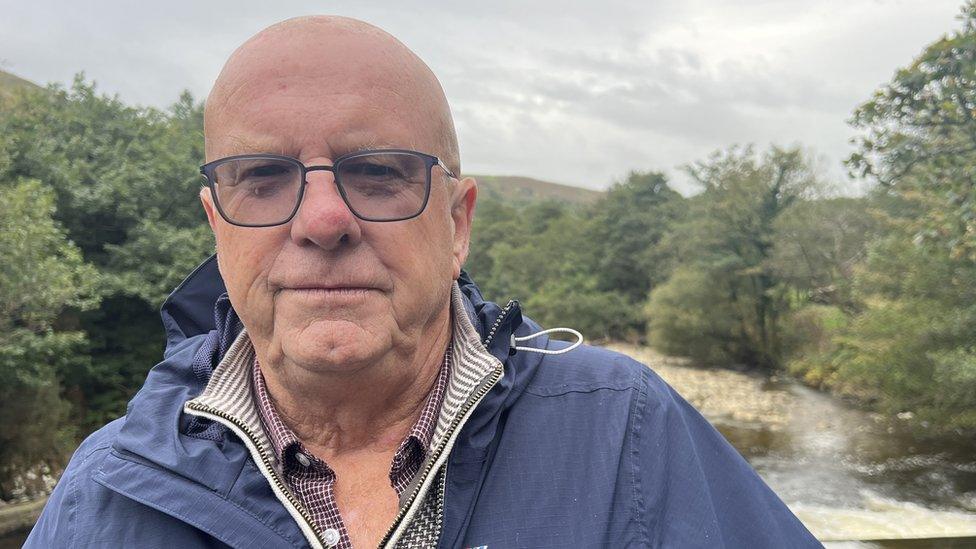

John Phillips, of the Afan Valley Angling and Conservation Club, says the river is "the lifeblood of the valley".

The club is supporting a waterways project aiming to improve the ecosystem and protect the local economy.

The work is a joint venture, led by Swansea University, to "open up the river" by removing physical barriers like weirs.

The Atlantic salmon species is believed to have swum and bred in Welsh waters for thousands of years, featuring in folklore tales since the last ice age.

John was a young boy growing up in Afan Valley, south-west Wales, when he first went to the river.

Now in his 70s, he said the project was "absolutely personal" to him.

John said the river was so polluted years ago due to the nearby mines, that "you wouldn't look for the fish to rise, you'd listen for them to cough".

Atlantic salmon, like those seen in this stock image, are believed to have populated Welsh rivers for thousands of years

The Afan Valley has about 100,000 visitors a year who go fishing or cycling on the routes nearby.

John said barriers like weirs - which are built across rivers and streams to control water level - "impact on the future survival of the fish".

"If we don't get visitors here to go fishing then the whole valley will suffer," he said.

For the same reason, he says he will still go fishing but, unlike when he was a child, he will never keep his catch - with many others doing the same.

John said the area's history goes back to the Cistercian monks of Margam Abbey in 1147.

But it was not until 1977, when the angling club bought the river, that the waterway got its first Welsh owners.

"Since then the club has been very active in trying to improve the river," he said.

Although the project is focused on salmon, experts said they were just a representative of how the work will boost the whole ecosystem of the River Afan.

John Phillips has been fishing in the River Afan since he was a child

Prof Carlos Garcia de Leaniz, the project lead from Swansea University, said: "It doesn't matter if you fish for salmon or you don't know anything about this species, we all need rivers.

"This is about biodiversity, this is about people, this is about our ecosystems and natural capital."

Prof Garcia de Leaniz said Europe has had "probably the highest density of artificial barriers anywhere in the world" for hundreds of years, despite the fact many of them are no longer serving their purpose.

The project, entitled Reconnecting Rivers, is "one of the simplest, most effective things that we can do to increase the resilience of our waterways", Mr Garcia de Leaniz added.

Trefor Prothero, a fourth-generation farmer, got involved with the project to work with the environment his family had been a part of for generations.

His farm, of about 200 acres, includes a weir nestled within an area of woodland which the project approached him about removing.

"We're trying to improve it as we go along," said Mr Prothero.

"We said carry on because it sounded quite important to do what we can to help the fish survive."

Harriet Alvis, of the West Wales Rivers Trust, says the weirs are "impounding" pollution in the river

The link between river health and pollution is also something the Reconnecting Rivers team feels strongly about, despite it not being the central focus.

Harriet Alvis, chief executive of West Wales Rivers Trust, said: "If you were, for example, to get a sewage pollution spill into a section of river, but just downstream there was a weir, then that is then impounding that pollution behind that weir.

"That means it's not diluting as quickly and there's fish or other life that's in that sewage for longer and so suffering the impacts of it more."

Jamie Carruth, fisheries and monitoring officer at the Wye and Usk Foundation, agreed, adding: "With this one action we can affect the populations of a whole number of species."

THE CRASH DETECTIVES: Every serious incident on the road requires forensic examination

CROSSBOW KILLER: Investigating the case of a Welsh murder stranger than fiction

Related topics

- Published26 July 2022

- Published8 July 2022