Man retraces great-grandfather’s epic World War Two escape

- Published

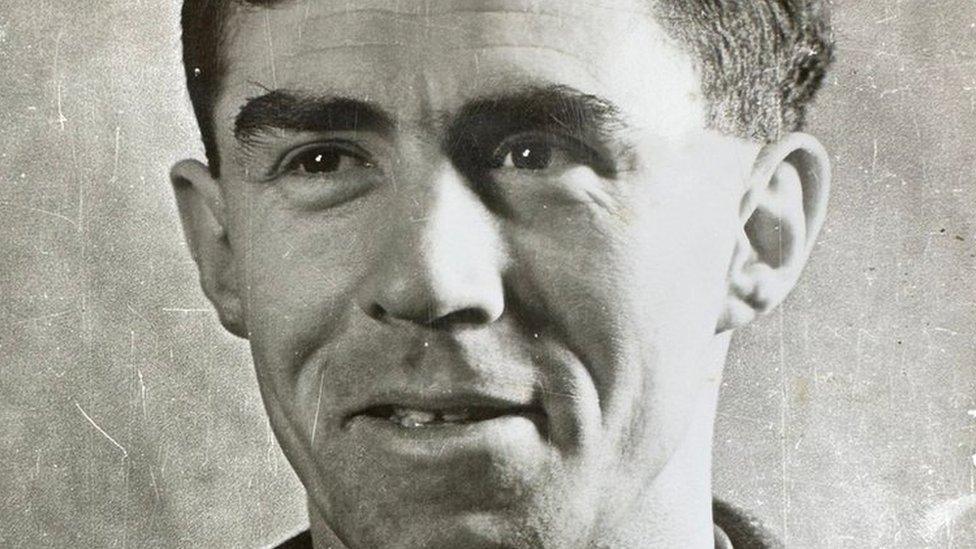

Squadron leader Frank Griffiths was the only survivor when a seven-man crew was shot down

Eighty years ago, squadron leader Frank Griffiths escaped Italian-occupied France during World War Two.

He was the only survivor of a seven-man crew whose RAF bomber was shot down in August 1943.

His escape was the culmination of a three-month journey which saw him cross some of Europe's highest peaks, hiking 80 miles (128km) in three nights.

Now his great-grandson, Adam Hart, has retraced his epic trek to safety on foot.

Joined by his uncle, Mr Hart said they set out to visit the places and "wonderful families" his great-grandfather would have encountered.

But even as an accomplished athlete himself, Mr Hart said the physical ordeal gave him even more respect for his ancestor.

"I've competed in Ironman competitions, but I was in no way prepared for the sapping effort the climbs and descents would take," said the 22-year-old from Narberth, Pembrokeshire.

"And we weren't even looking out for Nazis as we went!"

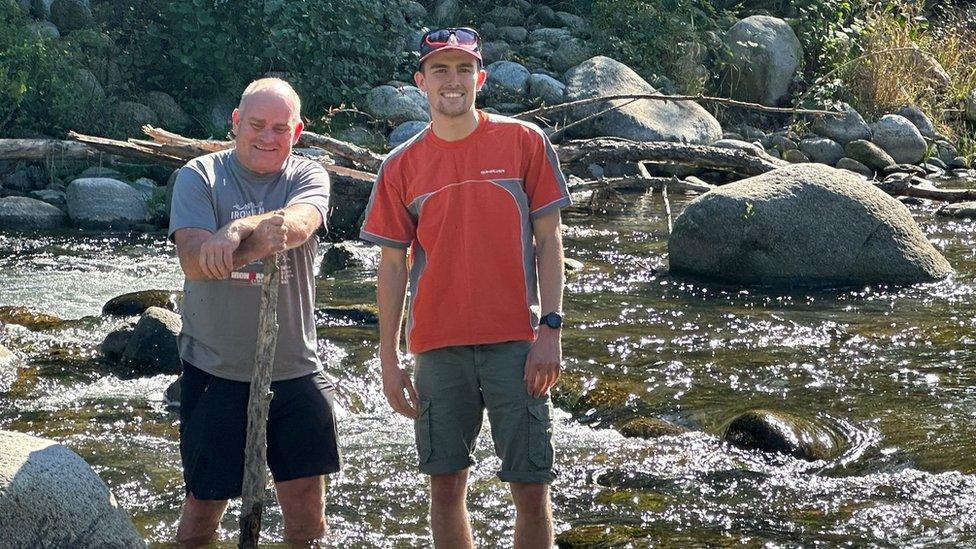

Adam Hart and his uncle Alex Holland retraced Frank Griffiths' footsteps across the Pyrenees

"[We] tried to stick faithfully to his route, and I'm so pleased about that, it gave us an understanding of what he must have gone through far more than any photographs or car trip could have done," said Mr Hart.

Griffiths was part of the RAF's 138th squadron, whose Halifax planes were adapted to carry cargo and men behind enemy lines.

They had been on a mission to drop supplies to French resistance fighters, when a lucky pot-shot from an Italian soldier's rifle punctured their fuel tank over the town of Meythet.

Griffiths only survived because he was flung from the cockpit, and his fall was broken by telegraph wires.

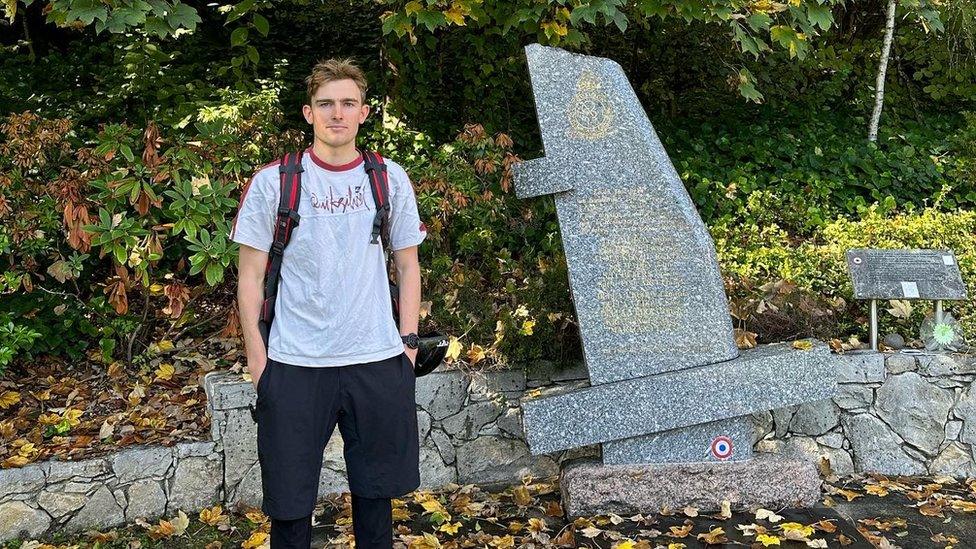

Adam Hart visited the memorial to his great-grandfather's fallen crew

With a broken arm, facial injuries and severe concussion, he was barely conscious enough to crawl away from the fireball as his plane exploded.

But in a miraculous stroke of luck, the inferno provided enough of a distraction to the Italian troops to allow a 14-year-old French boy to spirit Frank away on his bicycle.

The French resistance group smuggled him into Switzerland and treated him for his injuries.

By October 1943, he was well enough to attempt his escape back to Britain.

But the winds of fate were yet again to change direction.

"As Frank hadn't officially entered the country, the Swiss authorities offered him the option of being interned under the Red Cross, or they'd turn a blind eye and let him take his chances re-entering occupied France," said Mr Hart.

"Frank felt it was his duty to try to get back home to re-join the war effort."

Mr Hart said his great-grandfather planned to hitch a train to northern France and fly out by RAF Lysander, but by the time he had crossed back into Annemasse near Lyon, the Gestapo had moved in and the resistance group who rescued him had gone to ground.

"Everything was going wrong, he was wandering around in the dark after curfew. He'd just been forced to swallow the piece of paper with his coded instructions, when he was dragged into a house by a different resistance group," he said.

"Even if the Gestapo couldn't spot a lost British airman, they certainly could."

Walking at night and sleeping in sympathetic farmers' barns during the day, this group took him on a circuitous route through Toulouse and Perpignan, before leading him and two American airmen over an eastern pass of the Pyrenees.

'Always a proud Welshman'

For everyone's safety, no names were ever asked nor given.

Yet Griffiths once broke that rule on the trip, gifting the young son of a resistance fighter his French-English dictionary and writing in the front page: "English man Griffiths".

"I don't know why he did it at all given the danger, but I especially don't know why he wrote 'Englishman', Frank was always a proud Welshman," said Mr Hart.

He said he was glad the risk had been taken, because the Saque family were eventually able to reach out to Griffiths through the RAF in 1973, and he had the chance to visit them.

"Fifty years on from that, and 80 years after Frank first met the Saques, we were able to meet them too."

Mr Hart was introduced to a woman who had been a newborn baby in 1943, the same age as Griffiths' own daughter, who had been six weeks old when he'd last seen her.

"I have two photos side by side, of Frank holding both babies," he said.

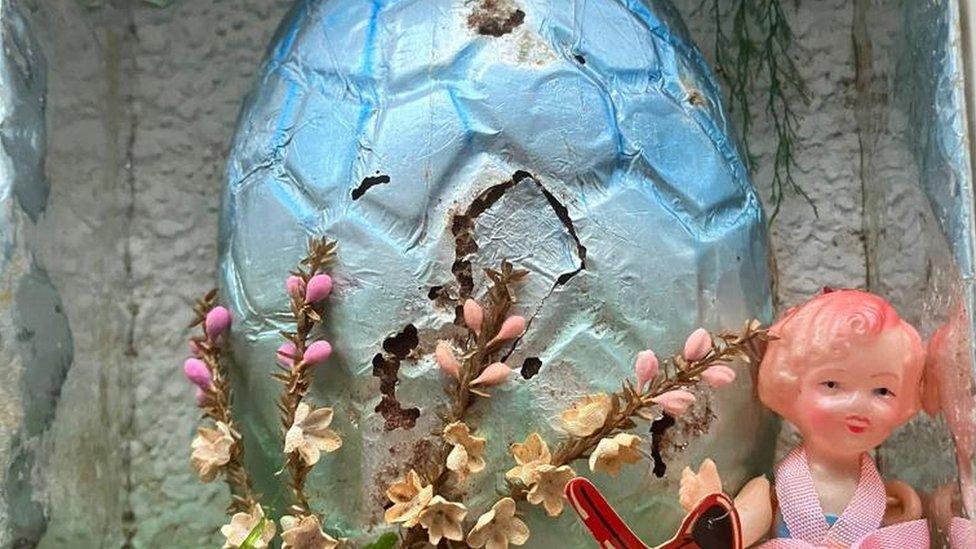

"When the Saques showed me Frank's dictionary, I couldn't understand at first why they were laughing. Then they explained that the teenage boy Frank had given it to had gone through the pages and underlined all the rude words.

"It was touching to see how it was still one of their most treasured possessions."

The boy's granddaughter organised a lunch and invited her friends and family, and then the pair were shown all the sites where Griffiths was hidden.

"It was really quite an emotional day," said Mr Hart.

After bidding farewell to the Saques in Spain, Griffiths was briefly arrested by the Spanish before being allowed to make his way on foot to Gibraltar, where he caught a flight home.

After that he was stood down from frontline duties, but remained a test pilot with the RAF until the 1970s.

He died in Ruthin in 1996, aged 84.

WALES' HOME OF THE YEAR: Which home will be crowned the winner?

BAFTA CYMRU WINNERS: Check out these award winning shows

Related topics

- Published19 May 2019

- Published21 April 2023

- Published13 November 2022

- Published15 September 2020

- Published4 January 2021