Great Fire of Builth Wells spared lives and stemmed plague

- Published

The White Horse Inn used to be the Red House, or Builth's only brick building

At first glance, London and the mid Wales market town of Builth Wells appear to have little in common.

But it was 333 years ago this week that Builth suffered a devastating fire similar to the inferno that ravaged the much larger city 24 years earlier.

Half the timber buildings in the Powys town were destroyed in what came to be known as the Great Fire of Builth.

And remarkably, just like the Great Fire of London in 1666, there seem to have been few or even no casualties.

Most sources suggest it tore through Builth on 27 December 1690, although some experts believe it may have been a week earlier.

What is known is that losses of £10,780 were recorded, or tens of millions of pounds in today's prices.

Mal Morrison, author of Builth Wells Through Time, said that while we cannot be certain about the loss of life, the clues point to it.

This 18th Century map of Builth Wells indicated where the fire happened

"What records we have go into quite some detail about the damage, but the absence of any recorded deaths or injuries do seem to suggest that there were none," he said.

"This is especially the case as the fire took place in the very wealthy mercantile town centre. You might have expected the odd farmhand to have been overlooked, but if any of Builth's elite had been harmed then it almost certainly would have been noted."

In another echo of the Great Fire of London, it is thought the Builth blaze may also have helped to stem a plague outbreak which had been prevalent in the town throughout 1690, by burning out disease-carrying rats and dispersing them into the surrounding countryside.

'Started by a careless servant'

A 1673 report for the Archbishop of Canterbury put Builth's population as 373, and it is unlikely it would have altered greatly by the time of the fire.

Having received its royal charter from Edward II in the early 14th Century, it had already been a prosperous market town for almost 400 years, initially serving the Norman castle, and then flourishing from its handy location on both the north-south and east-west routes across Wales.

According to lawyer and Brecknockshire historian Theophilus Jones, writing about a century later, the fire was started by a "careless servant".

The remains of the Norman castle which helped Builth become a prosperous market town

"Aided by a fierce west wind, raged for five hours, consuming the dwellings of 40 substantial families, with all their corn, furniture, affects and merchandises, to the great impoverishment of the adjacent country, and the decay of trade," he wrote.

Much as had happened in London, townsfolk battled the inferno. Bucket chains of men fetched water from the nearby River Wye, and demolished unaffected wooden buildings to create firebreaks and stop the flames spreading further.

However, no sooner was the fire out than efforts began to raise funds for Builth's rebuilding.

Mr Morrison explained how they set about an early instance of crowdfunding.

"The Gwynne family of Llanelwedd and Garth had acquired the lordship of Builth some 200 years before, and were on good terms with the newly-crowned joint monarchs William III and Mary, following the Glorious Revolution the year before.

'In the King's good books'

"The Gwynnes persuaded the King to issue 'letters patent', to allow the sufferers of Builth to collect 'alms' towards the fire.

"These weren't a loan guaranteed by the King, or even an investment. It was more a declaration that anyone who was seen to have donated would thereafter be in the King's good books."

It is unclear exactly how much this raised, although donations started coming in as early as January 1691.

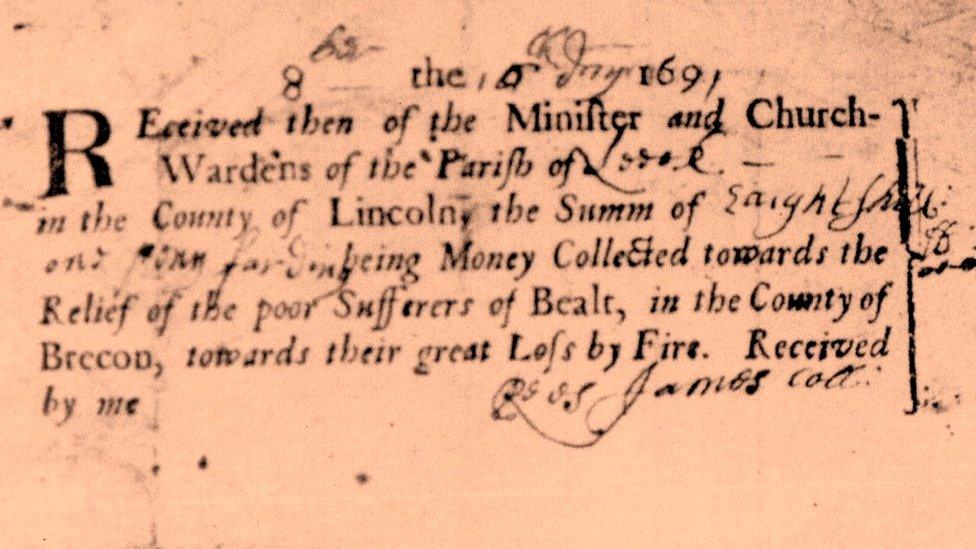

This receipt from January 1691 records some of the fundraising to rebuild Builth

One receipt acknowledging a contribution of "eight shillings and a penny farthing, collected by the minister of churchwardens of the parish of Lorakes in the county of Lincoln, being money collected towards the relief of the poor sufferers of Buallt (sic), in the county of Brecon towards their great loss by fire".

However, very little of this money saw its way to the ordinary people, and only one new building was ever constructed.

According to Mr Morrison: "The Red House, so called for its unusual appearance as the only brick building in Builth, is now the White Horse Inn. It was a fine effort, designed by architect Edward Price of Abercynithon [just west of the town], but it was the only thing to go up from the fund.

"The trustees were clever, they never laid themselves open to allegations of stealing the capital; what they did was to invest the donations, 'on behalf of the town', then lived very happily off the interest."

Meanwhile the ordinary inhabitants of Builth were forced to plunder the town's Norman castle in search of rebuilding materials.

Higgledy-piggledy streetscape

Sacked by Oliver Cromwell's army during the Civil War, the castle had been badly damaged for more than 40 years.

Yet by the time the locals had carried away stone, timbers, lead and tiles, nothing remained other than the turf motte on which it had been built.

It is said that many Builth buildings contain castle material to this day; though the resultant higgledy-piggledy streetscape did not greatly please Theophilus Jones.

"Whatever it may have been formerly," he wrote, "its present appearance, though it is situated in the most romantic and beautiful country, does not convey to the traveller any favourable ideas, either in the knowledge of the inhabitants in architecture, or their attention to the comforts and conveniences of life".

In the intervening centuries Builth Wells has been no stranger to fires; one in 1905 burning down the side of High Street which now contains Boots and the Barclays bank.

But with a sense of circularity, it was yet another blaze 50 years later which gave rise to Builth's most famous attraction.

"In 1955 the family seat of the Gwynnes in Llanelwedd burnt down," said Mr Morrison. "When it proved too costly to repair, the family sold up to the local authority, creating the space which is now the Royal Welsh showground.

"So you could say, after all these terrible blazes, Builth did finally rise like a phoenix from the flames."

Related topics

- Published2 September 2023

- Published27 June 2020

- Published24 December 2015