Waltzing Matilda: The Welshman who lived the swagman life

- Published

The term swagman, meaning itinerant farm worker, started in the 1800s in Australia

On this day 155 years ago, a lonely and depressed west Wales man set sail for Australia to become possibly the most famous "jolly swagman" of them all.

Joseph Jenkins - who lived the kind of life later immortalised in the Australian folk song "Waltzing Matilda" - came from Trecefel, Tregaron, in modern-day Ceredigion.

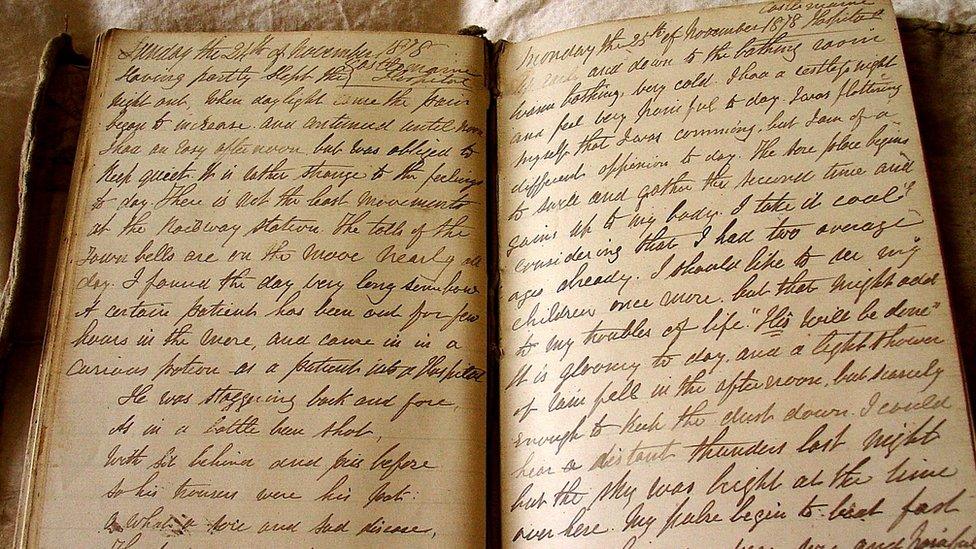

The diary he kept each day for 25 years as a "Swagman", or itinerant farm labourer, in Victoria is one of the most comprehensive and contemporary descriptions of colonial life in Australia.

But Joseph was neither "jolly", nor - by birth at least - "a swagman".

A swagman was someone who does not have a permanent home or job and moves from one place to another, or from one job to another with their belongings.

His diaries, lost for 80 years until they were rediscovered in his grandson's attic, run to 25 volumes, covering over 50 years of his life.

They are variously written, either carefully in quill-and-ink in bound books, or scribbled in pencil on scraps of paper, as his circumstances allowed.

His biography, Pity the Swagman, by the late historian Bethan Phillips, has recently been reprinted by Y Lolfa.

The diaries themselves, Diary of a Welsh Swagman, by Joseph's grandson William Evans, have been a set-text for Australian high school pupils since 1978, although now their unedited form has been digitised for viewing on the website of the State Library of Victoria.

The diaries are all written in various inks, scribbled pencil or scraps of paper added in

Their archivist, Shona Dewar painstakingly photographed all 5,600 fragile pages, before typing the text online.

"They provide a detailed account of life in Victoria for 25 years between 1869 and '94; a chronicle of changing economic, political and social conditions," she says.

"It is just one person's perspective and Joseph never visited other parts of Australia. Nonetheless, it is rare to find such a sustained and eloquent narrative covering such a long period."

Joseph was born a moderately wealthy tenant farmer in Cardiganshire, and although self-educated, his friends included Lord David Davies of Llandinam, with whom he helped to plan the arrival of the railways in mid and west Wales in the 1850s.

Though by 1868 his diary shows how his growing unhappiness with his marriage to Betty, and his disillusionment with "turncoat" friends, had seen him slump into alcoholism.

Matters came to a head when he backed the Tory candidate at that year's general election, only for the Liberals to win by a landslide.

The resultant ostracization saw a 50-year-old Joseph suffer what would probably be called a nervous breakdown in modern terms, and cause him to pack his bags for Australia.

His entries for that period claim Betty would "twist his testicles" as he slept, and even how she and their maids had plotted to kill him, although it's unclear how much of this may have been paranoia on Joseph's part.

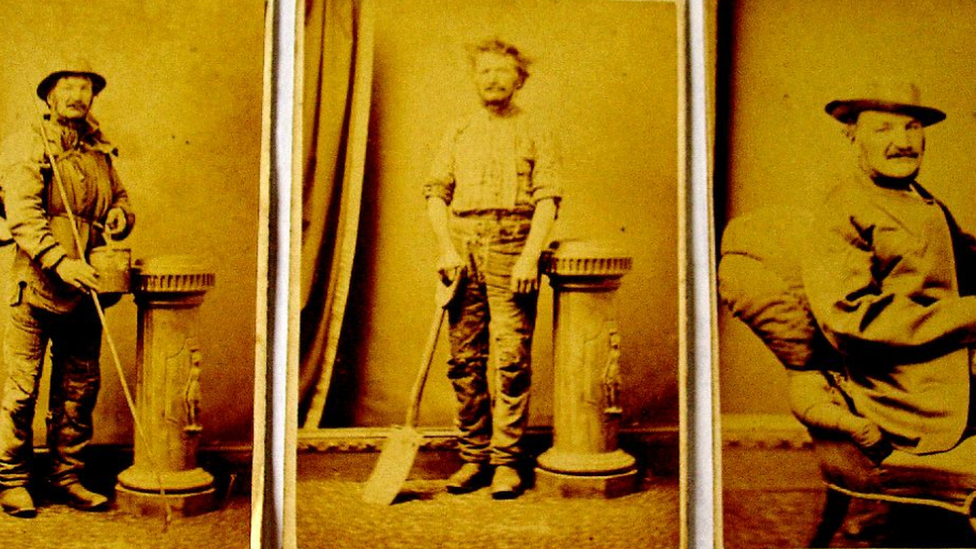

A photograph of Joseph in his working clothes taken in Ballarat in 1871

Ms Dewar said: "He suffered mental anguish at times and physical ailments plagued him as he grew older.

"Although the vast majority of his writing is in English, his angst about the treatment he felt he had received from his family is reflected in his comments in Welsh. I think he may have made his most bitter comments in Welsh in case prying eyes read them. Only fellow Welsh people would have understood them."

After arriving in Melbourne, Joseph initially worked as a Swagman, travelling from farm to farm to provide seasonal and temporary labour.

The wages were poor and the accommodation "inferior to that enjoyed by the horses".

Yet the hard work and long hours helped him to overcome his drinking.

A poem scribbled in one margin reads:

"From farm to farm in search of toil

"Begging for it while we can

"Improve and till the public soil

"Which God ordained for man"

Incredibly throughout this period, he managed to protect his diaries from some near-disasters, including: being covered in ink when the cork stopper came loose from a bottle in his pocket, being nibbled at by rats and scattered in the dirt when his makeshift hut was raided by bandits.

The repetitive nature of the work also helped him develop his political and social theories, becoming a progressive thinker before his time and writing on topics as varied as the rights of Indigenous Australians, poor farming methods which put profit ahead of the welfare of animals, fertility of the land and the folly of prospecting for gold.

Ms Dewar explained: "Joseph was progressive in some respects. He empathised with working people who struggled to get by in hard times, he believed that the land had been stolen from First Nations [indigenous] people by European colonisers, and he was very disapproving of the way European settlers were managing land in Victoria.

"On the other hand, he was intolerant of Catholics and Irish people who were, of course, often one and the same. He also had disparaging things to say about women, and particularly his wife.

"Though it's fair to add that he did have female friends, usually from the Welsh community there."

Joseph Jenkins and wife Betty lived in Trecefel, Tregaron, in modern-day Ceredigion

By 1884, aged 66, Joseph was too old for the Swagman's life, and found a more settled job as a street-cleaner in the town of Maldon.

As well as improving their drainage and sewage systems, he became something of a town elder, and was frequently called upon to give his thoughts on local and international events.

However, following the death of his brother, by 1894 he grew homesick, and feared never seeing his grandchildren - but even more so dying abroad with no-one to take charge of his precious diaries.

But his homecoming wasn't a happy one - he and Betty soon began arguing again - and having fallen back into drinking, he died four years later, aged 80.

Today Joseph is remembered with a drinking fountain at Maldon railway station, along with a plaque which quotes an entry from his diary: "Through this [diary] I am building my own monument."

- Published25 January 2024