Mental health: From breakdown to award-winning psychiatrist

- Published

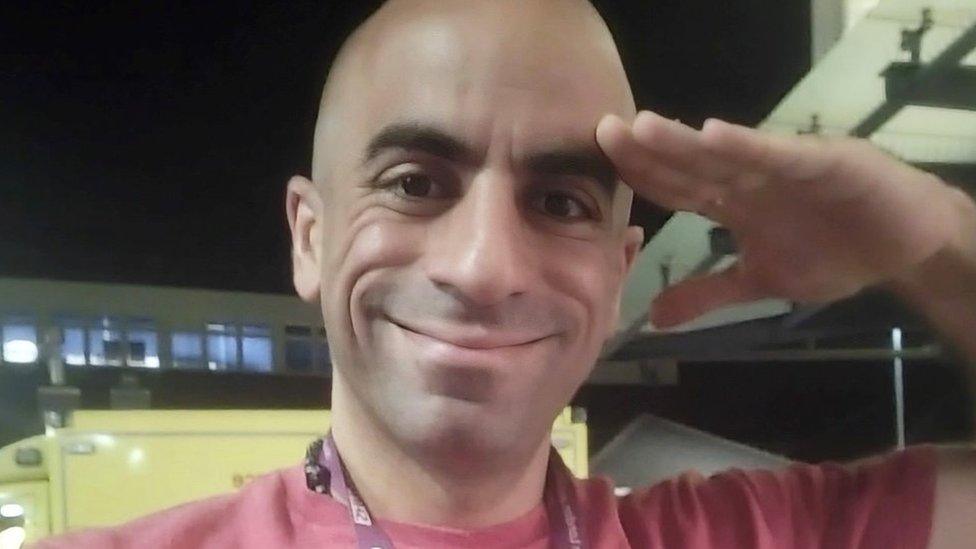

Psychiatrist Ahmed Hankir has built up a following on social media through sharing his own mental health journey

Eighteen years ago, Prof Ahmed Hankir was homeless and in the grip of a mental health crisis.

Today he is an award-winning psychiatrist working in Ontario, Canada.

His prestigious roles in the UK include honorary visiting professor at Cardiff Medical School.

By sharing his personal experience of living with a mental health condition and professional viewpoint, he now has thousands of social media followers.

"There's a solace in shared experience," he said.

"If you share, you can make other people feel less alone and less disconnected and less ashamed."

This article contains references to suicide.

Prof Hankir was born in Belfast, raised in Dublin and England, and moved to Lebanon at the age of 12.

"It was during the aftermath of the brutal and bloody civil war... the walls of the buildings would have bullet holes on them," he said.

Prof Hankir (far right) with his family in Lebanon in July 2000, just before he left for the UK

He was in Lebanon during the 1996 siege of Qana, external where more than 100 were killed and another 100 injured - one traumatic incident he experienced at that time would never leave him.

He recalled seeing a father returning home to see the building reduced to rubble and all his family killed.

"He was holding the dead body of his child in his arms," recalled Prof Hankir.

"I remember him crying inconsolably which kind of penetrated my soul. These memories continue to haunt me."

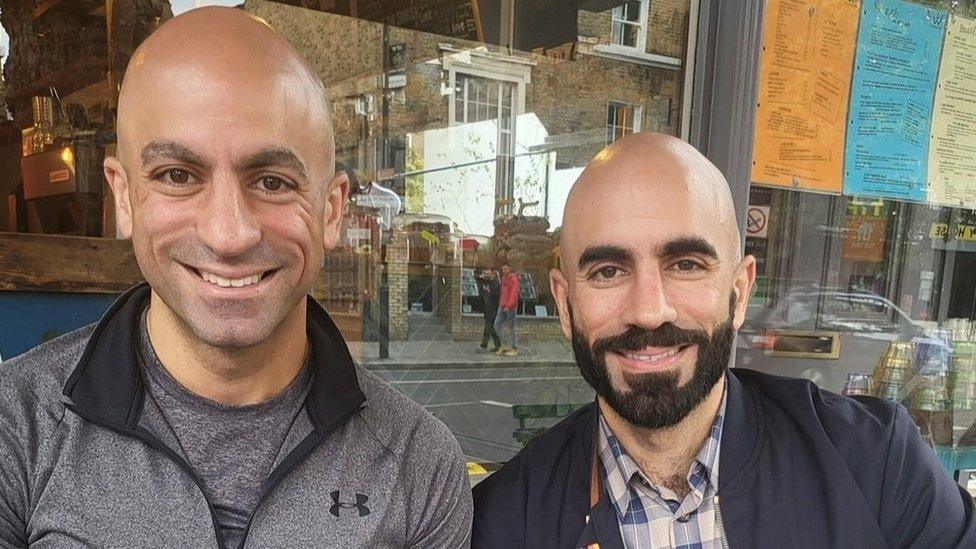

When he was 17, he and his twin brother left their parents and returned to the UK.

Prof Hankir moved back to the UK with his twin brother (right) when they were 17

Prof Hankir's dreams of going to medical school were dashed when he realised his qualifications gained in Lebanon would not get him into a UK university.

He also found he was considered an international student, so the cost of university tuition fees was prohibitive.

He began working in a kebab van where he experienced another traumatic event - a group of men beat a young man to death.

"They were about 20m away from the van... it was harrowing," he said.

"Nobody intervened, nobody did anything, everybody just watched it happen until we could hear the sirens."

At this point, the life he had hoped to create for himself felt completely out of reach.

"It was my dream to become a doctor and here I am serving kebabs on minimum wage, witnessing a homicide and people are asking me 'can you speak English?'," he said.

Next he worked as a janitor in the morning and stacked shelves at night, working up to 70 hours a week on minimum wage.

The following year he enrolled in sixth form college but continued to work full time.

Prof Hankir worked in a kebab van and stocking shelves before becoming a psychiatrist

On telling a member of college staff he wanted to become a doctor, he said she laughed in his face.

"She made me feel like I was this dirty little immigrant with delusions of grandeur," he said.

"She literally laughed and she said, to quote her verbatim, 'you can't get into medical school, it's too competitive, choose another course'."

He made it to medical school in Manchester but was badly missing his parents and struggling to balance working around his studies.

At this point, he began experiencing flashbacks and eventually reached breaking point.

"It was a major depressive disorder," he said.

"Pervasively low mood, thoughts and feelings of hopelessness and worthlessness and guilt, the ruminations, the inability to concentrate, having no energy, you can't even get out of bed, you've got no motivation and yeah, you feel suicidal.

"I was in a really bad state but I was just terrified of being sectioned and I was terrified of being admitted into a psychiatric ward."

He felt unable to get help.

"My perceptions of mental health and mental illness were influenced by my cultural background - we don't talk about mental health in the Middle East and North Africa, it's a taboo, heavily stigmatised," he added.

In 2006, he quit medical school.

"I was impoverished, I had nowhere to stay, I'm sleeping rough," he said.

He was sometimes able to sleep on a friend's sofa and for a short time stayed in a squat where one day he found a flatmate dead from a drug overdose.

"It was like one trauma after the other," he said.

He eventually sought help, was under a psychiatrist and gradually became strong enough to return to university.

"It was horrific and it was a slow, gradual and painful process to recovery," he said.

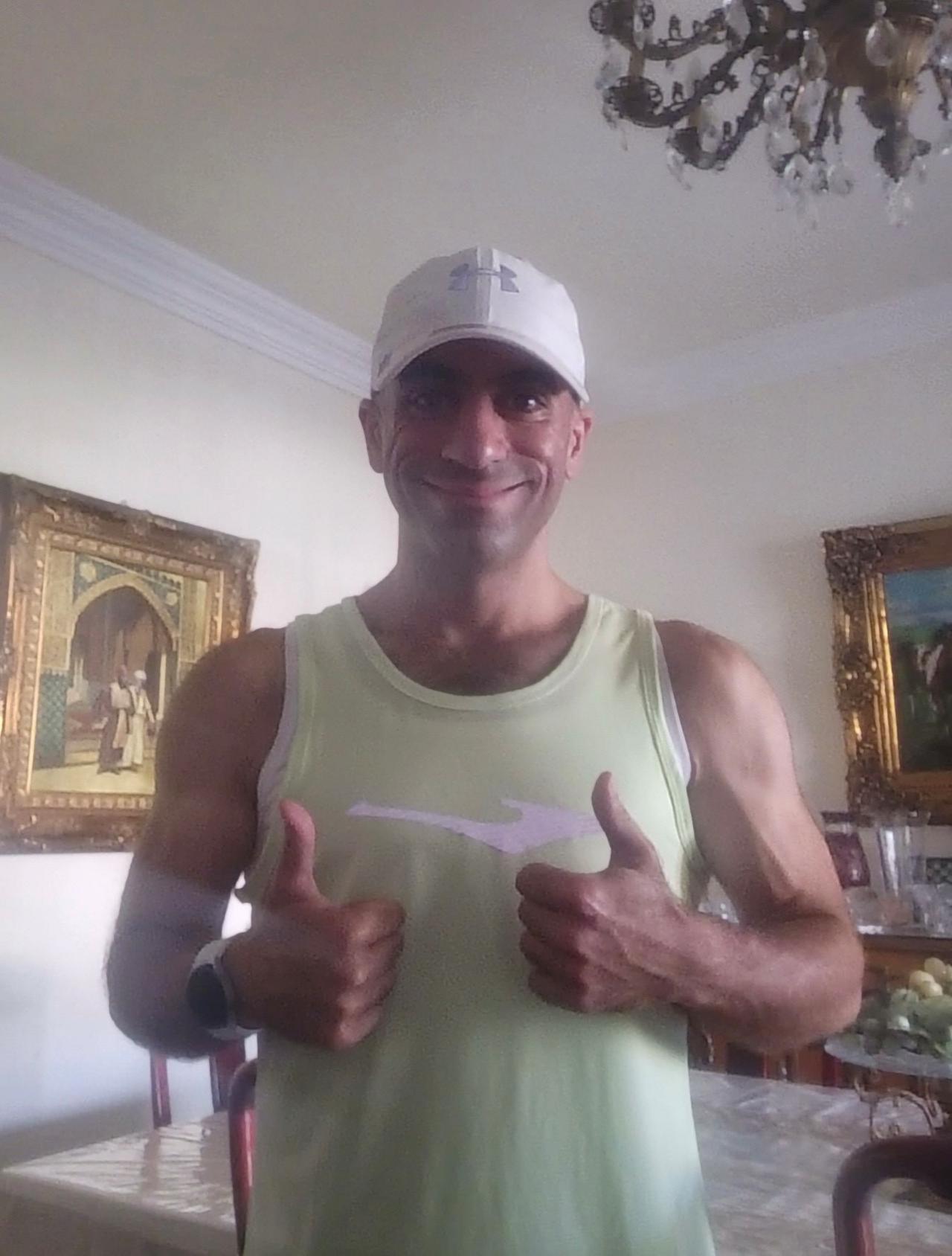

Prof Hankir says regular exercise helps him stay well

These days he considers himself someone who lives with a mental health condition but who has learnt resilience.

Last year he was awarded a World Health Organization Director-General's Health Leaders Award, external.

The same year he was awarded the Caroline Flack Mental Health Hero Award in The Sun's Who Cares Wins Awards for sharing his own struggles with mental health.

"I'm mindful that if I don't take the necessary measures to protect my mental health and to prevent relapse it can happen," he said.

He said exercise, his Muslim faith and working on creative projects aimed at combating mental health stigma all helped him stay well.

In April his book, Breakthrough: A Story of Hope, Resilience and Mental Health Recovery, will be published.

He believes the only way to end mental health stigma is to speak up.

"Just saying this with conviction: 'I live with a mental health condition, and I am not ashamed', that's how we could prevent suicide," he said.

He hopes to encourage other psychiatrists to share their personal experiences with mental health.

"Psychiatrists living with a mental health condition should not feel ashamed, they should feel empowered to talk to be honest, open, and transparent about their mental health experiences... I know it's a generalisation but maybe the British they tend to be more reserved and I respect that, but there's a lot of people who do want to share," he said.

"By revealing, by sharing, it lets other people know that they are not alone."

If you have been affected by any issues raised in this article, help and support can be found at the BBC Action Line.

- Published15 January 2023

- Published7 February 2024

- Published26 January 2024