Powys fossils 'shed new light' on ocean community evolution

- Published

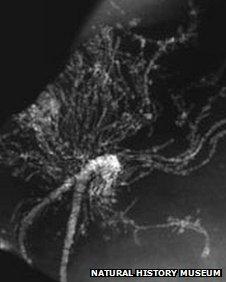

An x-ray scan of a solitary hydroid, similar to a sea anemone

Scientists believe they have made a remarkable discovery of fossils said to be more than 450 million years old in a disused Powys quarry.

They think they are of a kind never before discovered.

The well-preserved organisms from the Ordovician period, which began about 495m years ago, lived in what is now the town of Llandrindod Wells, which was partially under water.

Scientists believe they shed new light on how ocean communities have evolved.

The fossils include a variety of creatures from sponges and worms to nautiloids, which are similar to a squid with a shell.

They were found by palaeontologists Dr Joe Botting, Dr Lucy Muir and Talfan Barnie in 2004 and were revealed using X-ray scanning.

However, details of the significance of the find have only recently been published.

Dr Muir, a researcher at the Nanjing Institute of Geology and Palaeontology in China, said the discovery provided a picture of a fossil community that was entirely new and surprising.

They were found in Llanfawr quarry, an area well-known for its fossils, "but somehow the important fossils had been missed", she said.

The creatures' images are said to be 460m years old and from the part of geological time known as the Ordovician Period.

"There was an ocean between Scotland and England/Wales, and Wales was much further south than it is now," said Dr Muir.

"The area around Llandrindod was part of a chain of volcanic islands during the Ordovician Period, a little bit like Indonesia today.

"As the island grew and was eroded, a lot of sediment [sand, silt and mud] was washed into the sea. This sediment buried animal remains quickly, and in some cases buried them alive, so they didn't fall apart or get eaten."

Dr Muir said a variety of animal fossils were found, including sponges, worms, solitary hydroids which are related to sea anemones and are also known as the flowers of the sea, and nautiloids.

This is a picture of a nautiloid, which is similar to a squid with a shell

"Joe had been studying sponges from a particular quarry, and we went there to find some more," she said.

"We looked at part of the exposed rock that we hadn't found much in before. Talfan hammered part of the quarry wall, and said, 'Is this interesting?'

"It was one of the most astonishing fossils ever found in Wales. We took some slabs of rock back to the Natural History Museum, and one of my colleagues suggested X-raying them.

"On the very first slab we found a spectacular hydroid that we hadn't even suspected was there because it is entirely enclosed within the rock."

Later Dr Mark Sutton of Imperial College, London, who has helped to write the paper about the find, used a CT scanner to see the fossils in three dimensions.

Dr Muir called the discovery unique.

"Although there are a handful of sites around the world that preserve extremely delicate and soft animals in a similar way, none of them have preserved this type of ecosystem," she said.

"In particular, solitary hydroids are almost unknown in the fossil record, because they are so delicate.

"The new fauna gives us a picture of a fossil community that not only is entirely new, but is also surprising. It resembles to some extent some of the modern communities found in the very deep sea."

'Diverse and complicated'

The fossils have been given to the Natural History Museum in London, where they will remain.

"It's not a discovery that you can point to and say: 'This proves such-and-such,'" said Dr Muir.

"Rather, it's a question of adding a large new chunk of knowledge, and in turn suggesting that there are many more chunks left to find.

"This type of ecological community type was simply unknown from rocks this old, and for it to suddenly appear makes palaeontologists wonder what else they've been missing.

"It shows us that Ordovician ecosystems were even more diverse and complicated than we imagined."

- Published16 November 2011

- Published9 November 2011

- Published16 September 2011