Funeral for Bomber Command crewman Eddie Gurmin

- Published

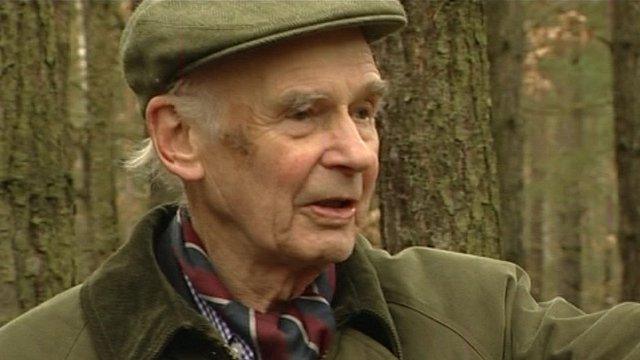

Eddie Gurmin helped build an escape tunnel in 1942 but chose not to join the breakout

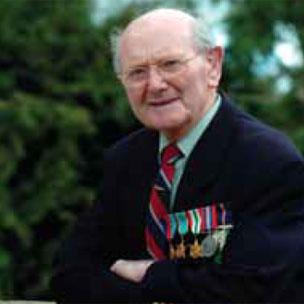

One of the last Welsh members of the RAF's World War Two Bomber Command crews is to be remembered by friends and family at his funeral later.

Tredegar-born Eddie Gurmin, who was 92, spent four years as a prisoner of war after his plane was shot down over Germany.

He spent time in Stalag Luft III, the notorious camp made famous by the Hollywood film The Great Escape.

Mr Gurmin will be buried in Llangynidr, Powys, where he spent his final years.

Weather permitting, his family hope the service will be marked by a fly-past of his former squadron.

They say the RAF has told them it will try to incorporate a tribute into a training exercise.

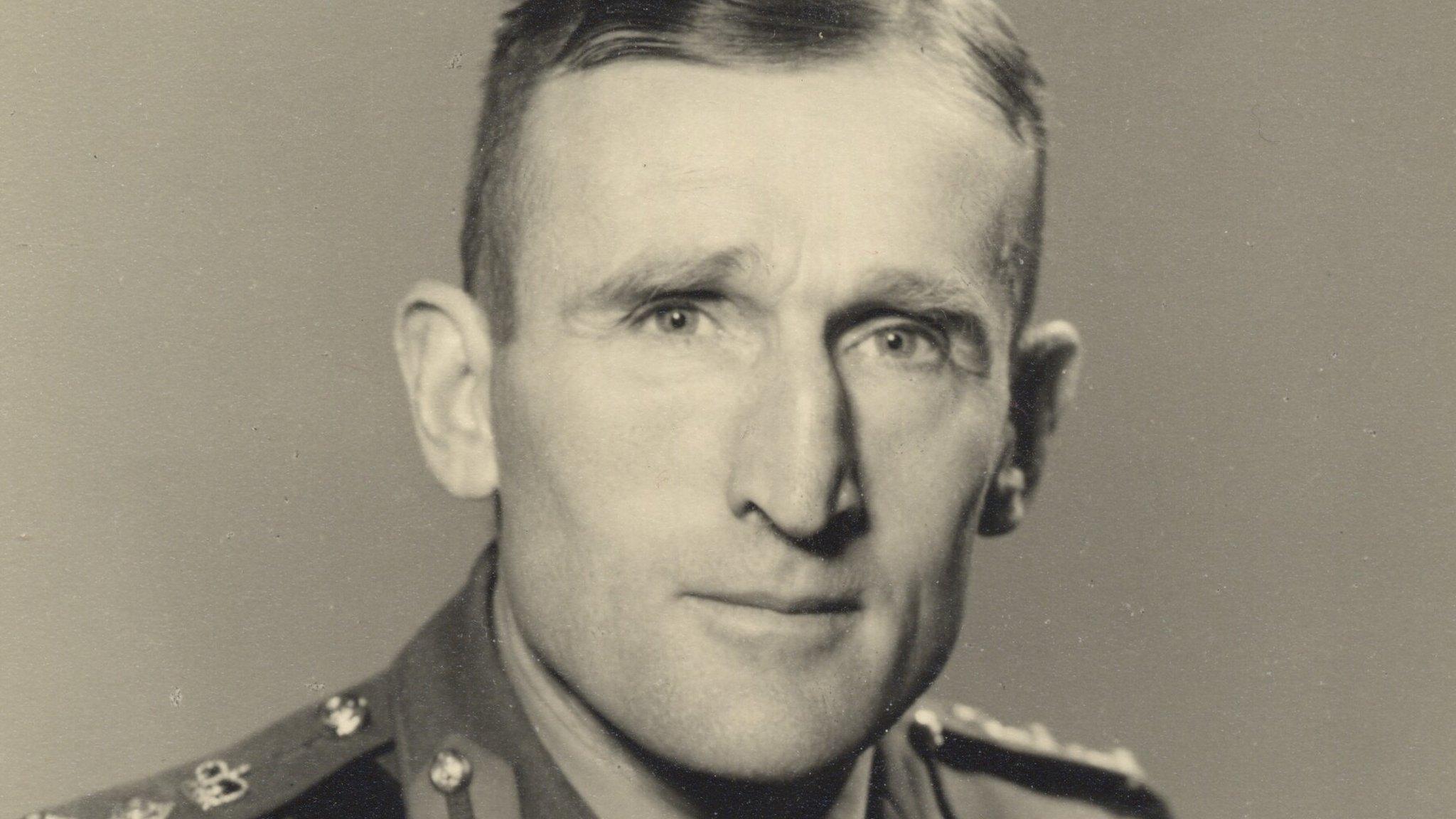

Edward Charles Gurmin was just 20 in 1941 when the Handley Page Halifax he was serving on was shot down.

He bailed out and spent the rest of the war as a prisoner in several camps, including Stalag Luft III.

Swapped roles

Daughter Gill Richardson said her father had already made his own "great escape" by changing his role on the fateful mission.

"On the night Dad was shot down he was on his 29th out of 30 bombing raids; after that crews were normally reassigned to ground duties for a while," she said.

"You might think that's unlucky, but not when you think that it was one of the first - if not the first - raid on which he'd swapped roles to become the wireless operator instead of the rear gunner."

RAF crew count out their successful bombing missions

Mr Gurmin described the scene as he jumped from his stricken aircraft in a book to mark the 60th anniversary of VE Day in 2005.

"When we bailed out we realised we'd had a direct hit with an ack-ack shell in the fuselage," he wrote.

"The whole of the fuselage had gone. All that was left was two wings and four engines.

"The rear gunner, of course, he'd fallen 15,000 feet - he was dead.

"At the same time we were attacked by a night fighter and he killed the front gunner … luckily I was on the wireless that night."

Mr Gurmin's parachute landed in the middle of a bog, in which several colleagues drowned.

He managed to find a solid path out, and began whistling "There'll Always be an England" in the hope of alerting any surviving comrades.

Instead, it drew the attention of the Nazi Luftwaffe officers on the very anti-aircraft battery which had shot his plane down.

His mother in Tredegar only learnt three weeks later that her son was still alive, via a broadcast by the German radio propagandist Lord Haw-Haw.

In the four years which followed Mr Gurmin endured many hardships in prisoner-of-war (POW) camps, including the record-breaking freeze of the 1941/42 German winter.

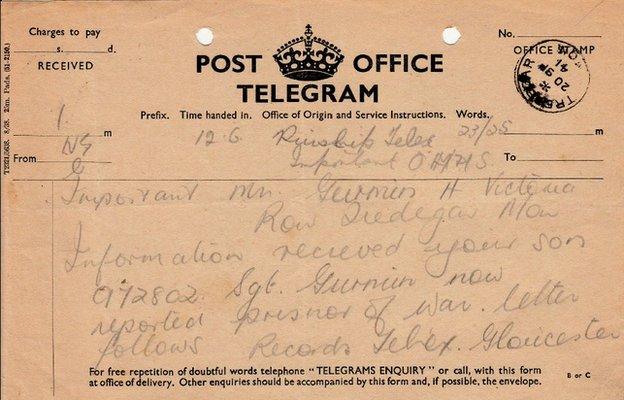

A telegram confirming Mr Gurmin had been captured as a prisoner of war

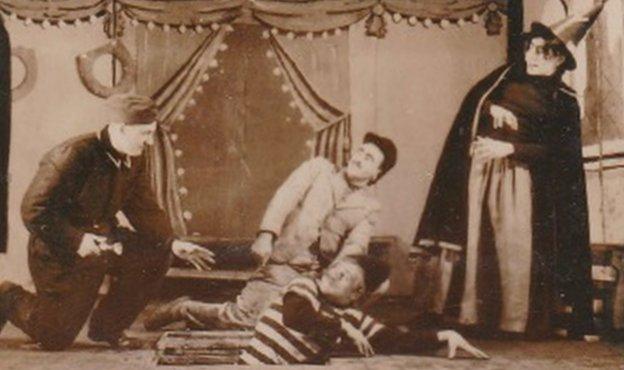

British officers perform Cinderella in 1941 at Stalag Luft I POW camp

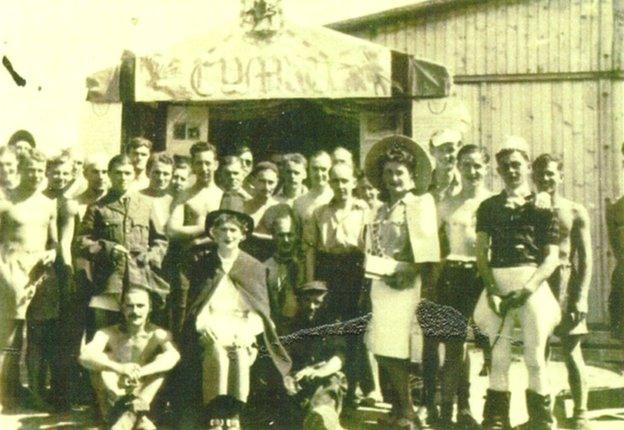

A strong Welsh flavour at Stalag Luft VI for this Jockey Club Gala Day in 1943

Two years before the famous Great Escape of 1944, he helped dig a tunnel from which 52 British servicemen escaped in May 1942, though he personally opted not to join the breakout, believing his chances of survival would have been minimal.

Mr Gurmin recalled hunger was the hardest thing he had to cope with.

"We would have a loaf of bread between about eight of us, and at lunch time we would have a cup of watery soup, with a couple of spuds boiled in their jackets, and a piece of German sausage meat."

Yet amazingly, Mrs Richardson says not all his memories of captivity were bad.

Eddie Gurmin bore no lasting ill-will towards Germany, his daughter says

"They'd spend their time joshing around and making friends. Their horseplay even ended up with Dad breaking his ankle at one stage," she said.

"They put on concerts, and one of the mementos we still have is a programme of a production of Cinderella, with costumes made out of parachute silk.

"He even learnt Welsh in captivity; though once he got home everyone laughed that he spoke Welsh with a German accent."

Indeed, Mrs Richardson believes her father's most harrowing memories came from after his camp was liberated by the Soviet Red Army.

"Unbelievably, the Russian troops were even more hungry than the British POWs - Dad was sharing what little food he had with them," she said.

"But the Russians behaved like animals once they got into Germany, and after Dad was allowed out of the camp, he volunteered to stay with a German mother and her children, because she was terrified of what the Russians would do to them.

"Eventually, his number came up and Dad was evacuated back home. He never found out what happened to that German family, and I think that was the thing which troubled him most of all about the war."

She says Mr Gurmin was remarkably unaffected in later years, making a living as a builder, and bearing absolutely no ill-will towards Germany.

In fact, she believes the only lasting effect was a dislike of confined spaces, which led him to move his family to their smallholding in mid Wales.

He died on 7 August.

- Published26 June 2014

- Published16 October 2013

- Published31 July 2013

- Published18 August 2012

- Published2 May 2014