Porthmadog bypass reveals more Roman life

- Published

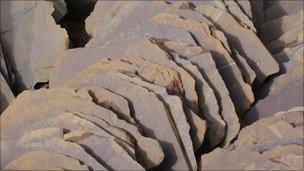

A photo of the Roman lime kiln on the route of the new Porthmadog bypass

Artefacts discovered on the route of the new Porthmadog bypass are making archaeologists rethink the way the Romans lived in the area.

The most significant find - a large lime kiln - was previously hidden under an earth mound.

The Gwynedd Archaeological Trust says the kiln, and slates from a building for high-ranking officials, indicate a large Roman settlement.

Building work began on the £34.4m bypass earlier this year.

Iwan Parry, from the trust, said the the presence of the roofing slates was documented after a dig in the area in the 1920s but the lime kiln was a complete surprise.

Parts of the lime kiln and a roofing slate at Porthmadog

"We're not certain of the dates yet because radio carbon dating has not been carried out, so this is really the beginning of the research we'll have to carry out," he said.

Mr Parry added the kiln was "huge" at round 4m (13ft) across and 2m (6ft) deep.

"They had cut into the stone - which would have been a lot of hard work - to create a bowl," he said.

"The purpose of the kiln would then be to create the lime for cement," he added.

As the land around the kiln had not been reclaimed from the sea at the time the Romans were around, the kiln would have been on a small island in the estuary, he said.

The slates are believed to have been used on a high-ranking building

"The kiln is a surprise too because we did not think there was any lime locally in Tremadog.

"The nearest source we thought was on Anglesey - but there might have been a type of lime around here" he added.

The roofing slates - cut into a diamond with two sides squared off - were first thought to be from the Nantlle Valley near Caernarfon.

Similar slates were then found at a barracks in Chester however, and they came from Bethesda (near Bangor), he said.

Wherever they are from it is still a significant find as the slates are "one of the first examples of Welsh slates being used as roofing", he added.

Excavation work on the bypass also revealed signs of human habitation in the area from 6,000 years ago.

"We found small bits of flint which they would have used," said Mr Parry.

"The location, on an island, would have meant there was a plentiful supply of food there in Mesolithic and Neolithic times."